Is all art in danger?

Capitalism, while it has allowed a small handful of corporate executives to dominate the entertainment industry for over a century, has also made way for artists that appeal to niche communities to find both their voice and an audience for their vision without the approval of or investment from large corporations. Many of these viewers are among those who are cutting their cable and searching for alternative forms of entertainment. In a society where six major corporations control all mass-media, growing numbers of people want to hear unique, authentic, and previously untold narratives that are not shared by these popular major networks and instead are available on-demand, shown in indie cinemas, written within online blogs, and presented on street corners. These independent artists, who were previously incapable of amassing a fan base without the name recognition and financial wherewithal of a major corporation, have become legitimate competitors and leveled the playing field in the 21st century by harnessing digital distribution and smart-technology.

RuPaul’s Drag Race, an American reality competition television series, is a show where drag queens compete for the title of “America’s next Drag Superstar,” through a series of challenges comparable to a mashup of America’s Next Top Model and Project Runway. The content may not be attractive to those who are not active followers of drag culture, a minority within the LGBTQ community, yet RuPaul’s Drag Race is celebrating nearly a decade of being on the air. Because of working-class access to efficient avenues for the successful independent production and distribution of art, all art is therefore not in danger of becoming the same, despite culture’s mass production.

The mass production of homogenous art is a symptom of the “Culture Industry,” a cultural theory proposed by Theodor Adorno in his book, Dialectic of Enlightenment. This industry describes popular culture as artificial, recycled, and soaked in capitalist ideology intended to permeate into the general population’s subconscious. Adorno argues that all art is either mass-produced or heavily influenced by the culture industry and that it significantly marginalizes or eliminates anything that doesn’t adhere to its ideological rules. While Adorno was correct about this theory during his lifetime since it was impossible to reach audiences on mass-media platforms in the twentieth-century without the aid of major corporations, he never benefitted from the use of a personal computer, and twenty-first century technological advances have provided an environment in which unique traits can thrive rather than be trampled out by consumerism.

In fact, in many ways independent artists have become the main benefactors of capitalism as the technology used to create and distribute content is now within reach of the working class. In 1965, Intel’s co-founder, Gordon Moore observed that the number of transistors per square inch on integrated circuits had doubled every year since their invention. He predicted that this trend would continue for the foreseeable future (Moore’s Law). By 2007, digital camera technology had achieved the equivalent quality of 35mm film. Directors no longer needed to shoot on film, send it away for processing and edit their work in expensive post production studios that had to be rented by the hour. Video could be captured directly to hard drives and edited on a personal computer. Production costs plummeted. With digital content and broadband internet becoming widely available in people’s homes, alternate forms of distribution became available to producers as well. These technological improvements in the creation and distribution of art caused software and equipment prices to drop dramatically.

RED Cameras, which are being used across big budget and low budget productions alike, can be purchased used for just under $15,000 and expensive lenses can be rented, bringing the creation of TV shows within reach of independent artists. Likewise, completely professional recording setups can be purchased for under $10,000. What used to require a major investment from a large company that makes decisions based on what content will be most profitable can now be financed by a few people with working class wages. Theodor Adorno, who died in 1969, was unable to foresee how Moore’s Law would affect these changes in the power paradigm of content creation in the twenty-first century. He could not predict that artists would become as autonomous as they have today. This enables them to be far less susceptible to the corruption of the culture industry and less vulnerable to having their artistic vision stripped of its individuality.

In RuPaul’s Drag Race, RuPaul begins each season by selecting contestants from independently uploaded YouTube audition videos. The drag queens that populate the show come from a range of diverse backgrounds in terms of experience and access. Some queens come on the show after years of success in the global queer scene, while others have yet to perform outside of their hometown’s underground gatherings. Throughout the show, participants get in drag and take on themed challenges, often involving costume design, lip sync performances, comedic routines surrounding queer life, and “reading,” which is drag terminology for making fun of one’s peers. Challenge winners are rewarded with cosmetic items, designer clothing, and queer vacation destinations and cruises. When the queens are not performing or working on their constructions, they are filmed sharing coming out stories, experiences with homophobia and transphobia, and discussing queer politics. The show depicts a vibrant and thriving queer culture living outside of the norm, something Adorno’s Cultural Industry deemed impossible. “The eccentricity of the circus, the peep show, or the brothel in relation to society is as embarrassing to [the Culture Industry] as that of Schoenberg and Karl Krauss,” yet, RuPaul has been providing a window into his perspective on these aspects of counter culture for ten years (Adorno, 108).

Those who agree with Adorno might respond to RuPaul’s Drag Race by arguing that this community has been adopted by the Culture Industry in its efforts to provide something for everyone and corner the market.

“Sharp distinctions like those between A and B films, or between short stories published in magazines in different price segments, do not so much reflect real differences as assist in the classification, organization, and identification of consumers. Something is provided for everyone so that no one can escape; differences are hammered home and propagated. The hierarchy of serial qualities purveyed to the public serves only to quantify it more completely. Everyone is supposed to behave spontaneously according to a “level” determined by indices and to select the category of mass product manufactured for their type. On the charts of research organizations, indistinguishable from those of political propaganda, consumers are divided up as statistical material into red, green, and blue areas according to income group” (Adorno, 97).

And indeed, RuPaul’s Drag Race is aired on VH1, a division of the multi-national, entertainment conglomerate, Viacom. Adorno could say that the show is no different from other productions, that its only purpose is to provide an “escape from the work process in factory and office…by adaptation to it in leisure time,” and that RuPaul’s Drag Race is not inoculated against “the incurable sickness of all entertainment” (109). Adorno would have a difficult time, however, explaining how RuPaul’s Drag Race conformed to the executive powers “tables, their concept of the consumer or themselves” (96). “The more all-embracing the culture industry has become,” Adorno claims, “the more pitilessly it has forced the outsider into either bankruptcy or a syndicate” (107). Yet, RuPaul is nothing if not an “outsider,” and he is flourishing on television.

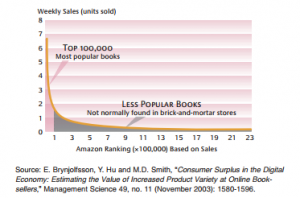

Adorno did not live long enough to see how Moore’s Law would impact content creation and distribution. He couldn’t predict The Long Tail that Chris Anderson first wrote about in Wired Magazine in 2004. The Culture Industry that Adorno cites is built upon Pareto’s principle:

“The 80-20 rule, also known as Pareto’s principle (after Vilfredo Pareto, an Italian economist who devised the concept in 1906), is all around us. Only 20 percent of major studio films will be hits. Same for TV shows, games, and mass-market books – 20 percent all. The odds are even worse for major-label CDs, where fewer than 10 percent are profitable, according to the Recording Industry Association of America” (Anderson).

The Long Tail represents the rest of the non-hit content that still has an audience. These consumers could not be served during the lifetime of Adorno, however:

“With no shelf space to pay for and, in the case of purely digital services like iTunes, no manufacturing costs and hardly any distribution fees, a miss sold is just another sale, with the same margins as a hit. A hit and a miss are on equal economic footing, both just entries in a database called up on demand, both equally worthy of being carried. Suddenly, popularity no longer has a monopoly on profitability” (Anderson).

The net value of The Long Tail may, in fact, be larger than the net value of the 20% (successful hits) Head. In “From Niches To Riches: Anatomy of the Long Tail,” published in 2006, authors Brynjolfsson, Hu and Smith discovered that although Barnes & Noble carry 130,000 titles, more than half of Amazon’s book sales come from titles that fall outside the top 130,000 sellers.

This suggests that niche markets make up more than half of the demand of entertainment. In Adorno’s time, the market was not capable of fulfilling this demand.

Today, however, the desires of the content producers can lead the marketplace. Independent artists can manifest their vision without the help or interference of a major corporation and find their audience. With increased competition, artists have more autonomy in the decision-making process and can leverage their specific appeal to niche markets for deals in the mass marketplace that would have been impossible during Adorno’s lifetime. These circumstances provide for an environment in which art is thriving. Artists have benefitted greatly from the competition among microchip makers to deliver upon Moore’s Law. Filmmakers, writers and musicians can work from their homes on technology that they can afford to access. Demographics which were once left out of the consideration set of executives at major studios can now garner attention and independent artists can connect with niche markets and monetize their vision without granting decision space to corporate executives who write the checks. More interestingly, well-crafted content generated for niche audiences, like RuPaul’s Drag Race, can find mass appeal and end up on Viacom.

Works Cited

Adorno, Theodor W., and Max Horkheimer. “The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception.” Dialectic of Enlightenment, edited by Gunzelin Schmid Noerr, Stanford University Press, 2002, pp. 94-136.

Anderson, Chris. “The Long Tail.” Wired, 1 Oct. 2004, www.wired.com/2004/10/tail/.

Brynjolfsson, Erik, Yu Jeffrey Hu, and Michael D. Smith. “From niches to riches: Anatomy of the long tail.” (2006).

Moore, Gordon E. “Cramming more components onto integrated circuits, Reprinted from Electronics, volume 38, number 8, April 19, 1965, pp. 114 ff.” IEEE Solid-State Circuits Society Newsletter20.3 (2006): 33-35.