Iron Man and the Corporate Doctrine of Rebellion

Rebellion has become the official aesthetic of consumer society. The anointed cultural opponents of capitalism are now capitalism’s ideologues.

Everyone loves a good rebel; a confident jerk who isn’t afraid of rules, an apathetic hero with some ‘tude. But what happens when it’s no longer clear what any of them are rebelling against—when rebellion stops being the exception and starts becoming the rule? Few seem to have noticed—we’re all too busy swooning over Han Solos and Ferris Buellers, and making not one but six movies about Steve Jobs—but it happened long ago. The original counter-culturists, most often associated with the Beats, had something to rebel against; enemies of conformity, they railed against the evils of mainstream corporate culture—you know, the guys who wanted everyone to buy the same Chevy and watch I Love Lucy every week. But soon, Hollywood was making movies like Rebel Without a Cause and later the films of John Hughes, and corporations from food tycoons to clothing giants were selling products with ads that championed non-conformity. Such corporate endorsements of rebellion may have excited some and angered others in the past, but today they are so thoroughly ingrained in our media that we accept them without consideration.

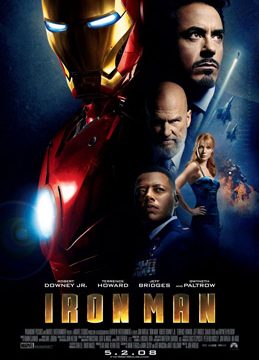

One such modern example is the movie Iron Man, which passed by with general critical acclaim and box office success (though not before ushering in the corporate behemoth that is the Marvel Cinematic Universe). It follows Tony Stark, an arrogant playboy and gazillionaire-tech-inventor, who gets captured by terrorists on a trip to Afghanistan and builds a big metal suit to escape, later perfecting the suit and turning himself into the superhero known as Iron Man. Stark is presented to us as a rebellious figure from the outset, first seen drinking a glass of bourbon and wearing a suit in the back of a military Humvee driving through the Afghan desert (not a setting most would choose for such lavish dress and activity), and then seen gambling with women instead of accepting a prestigious award—the rich philanthropist equivalent to cutting class. After this, we see him seduce a journalist, and the next day, keep a plane waiting for him for three hours without apology (rebels do not apologize for their actions). Later, in the terrorist cave, the other inventor in captivity tells Stark of the time they met at a convention, noting, “if I had been that drunk, I wouldn’t be able to stand, much less give a lecture on integrated circuits.” Showing Stark’s disregard for basic norms and rules that govern society, like not being inebriated at important public events, clearly characterizes him as a rebel. So why does this matter? The movie offers good evidence of how rebellion has become the dominant aesthetic of corporate culture, and how corporate culture now uses rebellion and ideas like it to surreptitiously further its goals.

One of these ideas, or themes, that plays out heavily in Iron Man is individualism. Original rebels like Ginsberg championed individualism in response to mid-century capitalist conformity; that is, until corporations started to champion individualism for the sake of profit. The more consumers believe in the importance of individuality, the less they believe in the importance of groups, of the public, of solidarity. While countercultural hippies rejected mainstream corporate culture in favor of social solidarity and connection, corporations now espouse this same rebellion to erode social solidarity, the one thing challenging their power. This has only intensified in the recent age of technology, in which every guy coding in his garage is heralded as the world’s savior, as opposed to some dusty old government or any kind of social movement. Boy, that does sound familiar… Iron Man is all about Tony Stark making stuff in his garage, and how he’s gonna change the world, all by himself. Upon his return from Afghanistan, he refuses to go to the hospital (a public service), opting to operate on himself instead. The movie then takes pains to show us that Stark works alone in his garage, with no other people helping him; instead he works with robots he’s created, conversing with them and in fact relying heavily on them, his companion Jarvis saving his life on multiple occasions. Besides one press of a button from his assistant Pepper in the end, Iron Man solves everything alone in the movie. To escape captivity, he builds an armored suit and breaks out. When he realizes all the harm his weapons are causing, he, unbeknownst to anyone, decides to shut down Stark industries’ weapons division. When he hears about the terrorist attack on the town of Gulmira, he flies there himself and kills all the terrorists. When it comes time to fight a bad-guy-iron man, he does the heavy lifting, fighting him almost entirely on his own (until trusty Pepper presses the magic button he tells her to press). On multiple occasions, he deceives and hides his weapon from the military. He also lives on a secluded rock and owns a private jet. All of these details build the corporate lone-wolf persona of Iron Man, something business always likes to see more of.

The movie briefly asks us to see the downside of this firm individualism, when the other inventor in the cave tells Stark, “you’re a man who has everything, and nothing” after Stark admits to not having a family. But this construes Stark’s problem as just a personal one, because he lacks close personal and familial ties with people—an issue that is supposed to be somewhat righted by Stark growing closer and starting to build a relationship with Pepper. While the concern for family values may be legitimate, there is no similar concern for the lack of general community values—the movie doesn’t see this as an issue. Stark building a powerful weapon and flying around the world in it fighting bad guys by himself is just cool; there are no apparent downsides or consequences. Thus individualism is upheld as one of the movies biggest messages—something that can’t be written off, as characters like Iron Man especially inspire millions of children and adults alike every day.

This being said, individualism is not the only modern corporate value evident in the movie. Much of conventional business thought today circles around breaking the rules, taking risks, forging your own path, etc. etc. As author Thomas Frank puts it, “perpetual revolution and the gospel of rule-breaking are the orthodoxy of the day.”[1] Tony Stark couldn’t embody these ideals any more fully. When presenting his weapons in the beginning, he says, “some say it’s better to be feared than respected. I say, is it too much to ask for both?” Here, he is consciously trying to break with convention as part of a bit to sell his product, and it works. Then, when he is captured by terrorists and told to make them a missile if he wants to live, he breaks the rules and builds an armored suit to escape. The correct response to this scene: “wow, he really thought outside the box there!” When he returns home and gives a press conference, he asks everyone in the room to sit down on the floor as he gives his speech sitting in front of instead of behind the podium, evoking the casualness and perhaps even pseudo-Eastern philosophies so cherished by today’s corporate moguls. Later, when testing out the flying capability of his new suit prototype, he decides to go outside on full power, responding to Jarvis’ warnings by saying, “Sometimes you gotta run before you can walk”—a line he could have substituted for any number of corporate slogans encouraging risk-taking and subversion of norms. The end of the movie then bookends this theme quite fittingly: Stark is given note cards to read at a press conference to dispel rumors about the suit and keep the peace—after some consideration, he decides to ignore the cards and triumphantly declare himself Iron Man. How much more symbolically could he stray from convention, forge his own path, and be a risk taker? Once, these concepts represented a daring, countercultural perspective. They may still seem that way to the average viewer, but by now, as demonstrated by movies like Iron Man, they have been so fully adopted as part of the corporate doctrine that they subvert very little.

It’s easy to dismiss all of this as over-analysis, that it’s just a film rendition of a comic book hero, an entertaining story detached from reality. But understood in context, Iron Man is fully representative of a larger phenomenon in our culture—one where corporations now champion individualist rebellion in opposition to social solidarity—and the lack of anyone to notice or care is exactly the point. One of the major victories for corporate culture that has come out of their adoption of rebellion has been their power over rebellious icons—not to be overlooked, because everyone loves a good rebel. Corporations like Walt Disney now produce and control the biggest rebellious icons of our day, and they have the power to make them the corporate individualists they want to see. Behold, Iron Man, children’s idol and patron saint of CEOs.

An earlier draft of this essay was read by Geoffrey Salmon.

I have written this essay in the style of Thomas Frank.

[1] Frank, Thomas. “Dark Age.” The Baffler, 29 June 2017, thebaffler.com/salvos/dark-age.