“Chick Flicks Don’t Have to Suck!”: Bridesmaids and Prescribed Female Roles

“Popular culture is often premised on the confusion of genders. It demonstrates over and over again that gender is not stable. Its stories and representations show gender to be fractured, fragile, or otherwise transgressive.”

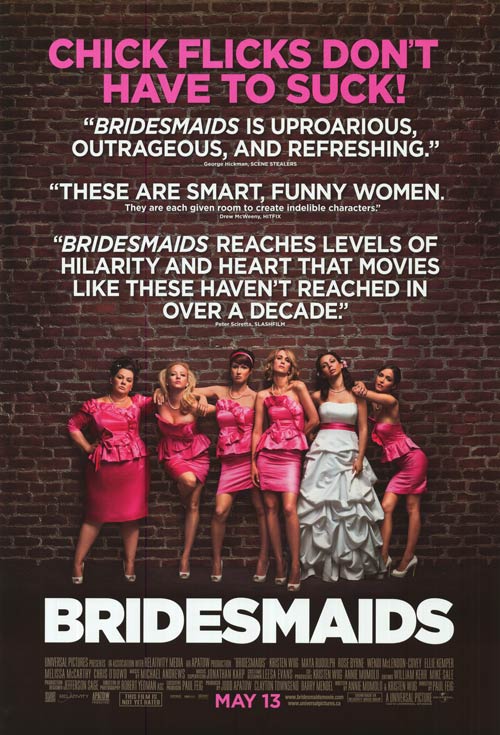

Did you know that the “feminist” movie Bridesmaids actually elaborately reinforces the sexism and gender roles that radiate throughout our society? For instance, did you know that the theatrical release poster to Bridesmaids reads: “Chick flicks don’t have to suck!”?[1] Did you realize that people who sit down in movie theaters to watch Kristen Wiig and Melissa McCarthy and Rebel Wilson’s antics wonder, “Who knew women could be so funny”? Did you know that this movie, which has been called a “breakthrough for feminism”[2], draws our attention to the infrequency of women in comedic roles? That it pushes the same prescribed gender roles as all other movies? Could it be that films that claim to bend gender stereotypes do no such thing?

Movies that have a female-led cast or crew say they are progressive and empowering. They are able to fool some people: Critic Mary Elizabeth Williams calls Bridesmaids the “first female black president of female-driven comedies”[3], while Helen Warner argues that although the movie’s “narrative is preoccupied with traditional ‘feminine’ themes such as female work, friendship, and romance…which often secure the rom-com as a critically maligned genre…Bridesmaids escapes such censure.”[4] I concede, these critics are not fully incorrect, as Bridesmaids and its counterparts do bring new dimensions to femininity. However, what exactly are these new views of women saying? Are they, in fact, simply providing more ways to align us with the societal stereotypes that have always existed? After seeing women in new positions – in this case, comedic ones – we still take with us the same impressions of their gender that we had beforehand. Bridesmaids gives women new ways to fill the same stereotypes that have always been attributed to their gender.

Bridesmaids is often referred to as the “The Hangover for women” [5], the chick-flick version of a male comedy that has dominated movie theaters worldwide. I grant, the intention behind this is harmless and even complimentary: the film allows women to embody a sense of humor that is typically reserved for men. Women get to show their wild sides; we see open drunkenness, sexual encounters, cursing, and pure masculine stupidity. We see the bridesmaids all get food poisoning and vomit. We see them drive recklessly and immaturely fight each other in a tennis match.

However, there is something overtly problematic in how we continue to “[call] comedies starring women chick-flicks. Women are funny. Men are funny. Bridesmaids is not The Hangover‘s sister, it’s not the same film dressed up in drag, or any other reinterpretation of it.”[6] This movie is only labeled “feminist” because it stars women in typical male roles. Its content is actually quite the opposite, as is how it causes us to view women. Perhaps the only similarity between Bridesmaids and The Hangover is that both are sexist and constraining.

To demonstrate how Bridesmaids defines gender norms, we must examine how the characters are portrayed. One well-known scene takes place on an airplane, while the bridesmaids are flying to the wedding. The scene focuses on Lillian (the bride), Annie (the main character, Lillian’s best friend, and the maid of honor), and Helen, who is married to the boss of Lillian’s fiancé. For essentially the entire movie, Annie and Helen are in a fight over Lillian.

In this scene, Annie has to fly business class while the rest of the bridesmaids and the bride fly first class, as she is having financial struggles. She gets drunk, starts to bother Lillian and Helen, and causes a huge disruption. When a flight attendant comes and tells her to return to her seat, she begins making fun of him. In this scene, a viewer cannot help but sympathize with the flight attendant (who, of course, is male). In contrast, in a scene from The Hangover, a police officer demonstrates how to use a Taser on Phil. Afterwards, a young boy shoots Alan in the face with the Taser, and the police officers and students fall over laughing.

A key difference here is that while other people make Phil and Alan into fools, Annie makes a fool out of herself. Because of this, it is hysterical when the men are embarrassed, while Annie’s embarrassing moment is irritating and frankly quite sad. We need to ask ourselves what exactly these differences show about out society. What does our laughter mean during these scenes? Why do we fail to acknowledge that when we laugh at men and at women, we are not laughing at the same things?

“Boys will be boys”, so goes the saying. In contrast, in Bridesmaids the women attempt (and fail) to be boys. When men do stupid things, it is acceptable and funny; however, when women act this way, they just seem plain dumb. One of the reasons we laugh in Bridesmaids is because women are trying and failing to be independent. The reason this chick-flick does not “suck” is because it masculinizes the audience and makes us laugh at women. Furthermore, we find these women funny because they are embarrassing themselves in their attempts to transcend gender norms. Men are allowed to embarrass themselves in films while also maintaining positive reputations; women make idiots out of themselves if they attempt to let their masculine stupidity show. Bridesmaids still clearly defines what is feminine and what is masculine because its humor is on the basis of taking away any respect we have for women by dumbing them down and lessening our expectations of them.

Another essential feature of Bridesmaids is that a majority of the comedy comes from pitting Annie and Helen against each other. This eliminates any hopes of gender norms being broken in the film. The whole movie is essentially one large catfight, something that is attributed almost exclusively to females. Never have I heard of a man referred to as “catty”; in male humor, fights showcase strength and aggression in at least one of the men. In Bridesmaids, the central fight is completely immature and feminine. Annie and Helen are feuding over who is Lillian’s best friend: this could not be more stereotypically female or less stereotypically male.

Bridesmaids also lacks the physical violence that male-centered comedies such as The Hangover are filled with. Two of the biggest “fight” scenes in Bridesmaids are when: 1. Helen surprises Lillian with tickets to Paris and 2. Megan (Lillian’s future sister-in-law) starts trying to knock some sense into Annie while the latter is busy feeling bad for herself. On Movieclips.com’s YouTube page, these clips are given the emotional, hyper-feminine titles “Why Can’t You Just Be Happy for Me?”[7] and “Pity Party”.[8]

In the first scene, Annie goes on a psychotic rant, starts attempting to throw things around at the bridal shower, and looks quite frankly like a complete idiot. The second scene perfectly demonstrates the type of physical fighting that is attributed to women: Megan starts poking Annie, they end up having a dysfunctional fight, and when Annie accidently slaps Megan she apologizes and the fight is over.

Comparing this to the Taser scene from The Hangover that I mentioned earlier, we see that even if the idea of having fighting in a movie is more masculine, the way in which Bridesmaids portrays this violence is clearly feminine. The point here is that women, no matter how masculine they get, are still masculine in a feminine way. Manly, physical humor must be modified before women are allowed to participate in it.

It now becomes clear that popular culture is not based on the confusion of genders, as Carol Clover argues in Men, Women, and Chainsaws.[9] In movies such as Bridesmaids, we are hyperaware that we are watching women in roles that are customarily filled by men. The confusion of the genders can only come if we are able to forget we are watching women onscreen. Instead, the movie’s defining feature is that although it is funny and appeals to a wide, mixed-gender audience, it is still no more than just a chick-flick. Even the ways in which critics judge this movie cannot escape gender constraints:

The criteria used to judge the success (or otherwise) of Bridesmaids – whilst often cohering with [an] emphasis on originality, quality, and comedy value – are nevertheless frequently gendered. So, for instance, in relation to originality, Bridesmaids is variously criticized as being “just” a chick flick, or praised for being “more than” a chick flick, as though the very presence of women in leading roles marks Bridesmaids as potentially generic. This is in contrast to reviews of The Hangover where judgments around originality are most commonly made in relation to specific other titles – in particular, Dude, Where’s My Car (Danny Leiner, 2000) and Very Bad Things (Peter Berg, 1998).[10]

Why are we surprised when we see women dominating the screen? Why does the idea that women are filling roles that are considered unnatural to their gender grab our attention? Why do supposedly freeing movies still perpetrate gender divides?

The reality is that Bridesmaids reinforces gender stereotypes at its foundation, as “[it was] made with a male director at the helm and women writers behind the scenes.”[11] A man controlled all of the film’s shots and general character portrayals. I concede that having female writers and actors is progress, but doesn’t having a male director somewhat negate this step in the right direction? A man designed how the women in this movie are portrayed. He conveniently pushed them into boxes and advertised this mockery as empowering. He has tricked women into laughing at their own deficiencies and failures.

Would you rather be seen as passive and put-together or autonomous and foolish? This is the choice that women must make. Pop culture cannot be based on gender instability if, as has been discussed, that which is perceived to be progressive and feminist so clearly is not. Men never have to make this choice because respect is built in to their gender identities; women must earn respect (although it is arguable whether this is even possible). Thus, no matter how masculine women may seem to be in films such as Bridesmaids, these movies do not actually portray gender as fluid. Even if stereotypes are pushed, they still are clearly intact and unbreakable. The idea that a woman with masculine qualities is called a “tomboy” or a “masculine woman” and not a “man” shows that we are still only being held in comparison to the other members of our gender. Gender benders will not exist until there are no gender boundaries left to bend.

Bibliography

Boyle, Karen. (May 2014). “Gender, comedy and reviewing culture on the Internet Movie Database.” Participations Journal of Audience and Reception Studies. Retrieved from http://www.participations.org/Volume%2011/Issue%201/3.pdf. Accessed 11 Dec 2017.

“Bridesmaids Theatrical Release Poster”. 2011. Image retrieved from http://www.impawards.com/2011/bridesmaids_ver2_xlg.html. Accessed 12 Dec 2017.

Clover, Carol. Men, Women, and Chainsaws. (United States: Princeton University Press, 22 March 1993).

Cox, David. (2011: June 27). “Bridesmaids buries Hollywood’s fear of feminism.” The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/film/filmblog/2011/jun/27/bridesmaids-hollywood-fear-of-feminism. Accessed 11 Dec 2017.

English 117: Introduction to Cultural Theory. (Williamstown, MA: Williams College, Fall 2017).

Feig, Paul. Bridesmaids. (United States: Apatow Productions & Relativity Media, 2011).

Movieclips.com. “Bridesmaids (8/10) Movie CLIP – Why Can’t You Just Be Happy for Me? (2011) HD”. Youtube. Youtube, 21 Dec 2015. Accessed 10 Dec 2017.

Movieclips.com. “Bridesmaids (9/10) Movie CLIP – Pity Party (2011) HD”. Youtube. Youtube, 21 Dec 2015. Accessed 10 Dec 2017.

Phillips, Todd. The Hangover. (United States: Warner Bros. Pictures, 2009).

Randall, Lucy. (Date unknown). “Madam With a Movie Camera: Gender, Industry, and Cultivating Creativity.” Retrieved from http://lucyrandall.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/REVISED-Madam-With-A-Movie-Camera.pdf. Accessed 10 Dec 2017.

Savage, Sophia (2011: May 23). “What Comparing Bridesmaids and The Hangover Reveals About Hollywood’s Gender Problem.” Indiewire.com. Retrieved from http://www.indiewire.com/2011/05/what-comparing-bridesmaids-and-the-hangover-reveals-about-hollywoods-gender-problem-237210/.

Warner, Helen. (2013). “‘A New Feminist Revolution in Hollywood Comedy’?: Postfeminist Discourses and the Critical Reception of Bridesmaids.” In: Joel Gwynne & Nadine Muller. Postfeminism and Contemporary Hollywood Cinema. (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013). https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1057/9781137306845_14.

[1] “Bridesmaids Theatrical Release Poster”. 2011. Image retrieved from http://www.impawards.com/2011/bridesmaids_ver2_xlg.html. Accessed 12 Dec 2017.

[2] David Cox. (2011: June 27). “Bridesmaids buries Hollywood’s fear of feminism.” The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/film/filmblog/2011/jun/27/bridesmaids-hollywood-fear-of-feminism. Accessed 11 Dec 2017.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Helen Warner. (2013). “‘A New Feminist Revolution in Hollywood Comedy’?: Postfeminist Discourses and the Critical Reception of Bridesmaids.” In: Joel Gwynne & Nadine Muller. Postfeminism and Contemporary Hollywood Cinema. (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013).

https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1057/9781137306845_14. Page 222.

[5] Sophia Savage (2011: May 23). “What Comparing Bridesmaids and The Hangover Reveals About Hollywood’s Gender Problem.” Indiewire.com. Retrieved from http://www.indiewire.com/2011/05/what-comparing-bridesmaids-and-the-hangover-reveals-about-hollywoods-gender-problem-237210/.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Movieclips.com. “Bridesmaids (8/10) Movie CLIP – Why Can’t You Just Be Happy for Me? (2011) HD”. Youtube. Youtube, 21 Dec 2015. Accessed 10 Dec 2017.

[8] Movieclips.com. “Bridesmaids (9/10) Movie CLIP – Pity Party (2011) HD”. Youtube. Youtube, 21 Dec 2015. Accessed 10 Dec 2017.

[9] Clover, Carol. Men, Women, and Chainsaws. (United States: Princeton University Press, 22 March 1993).

[10] Karen Boyle. (May 2014). “Gender, comedy and reviewing culture on the Internet Movie Database.” Participations Journal of Audience and Reception Studies. Retrieved from http://www.participations.org/Volume%2011/Issue%201/3.pdf. Accessed 11 Dec 2017. Page 44.

[11] Lucy Randall. (Date unknown). “Madam With a Movie Camera: Gender, Industry, and Cultivating Creativity.” Retrieved from http://lucyrandall.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/REVISED-Madam-With-A-Movie-Camera.pdf. Accessed 10 Dec 2017. Page 4.