A love song against love?

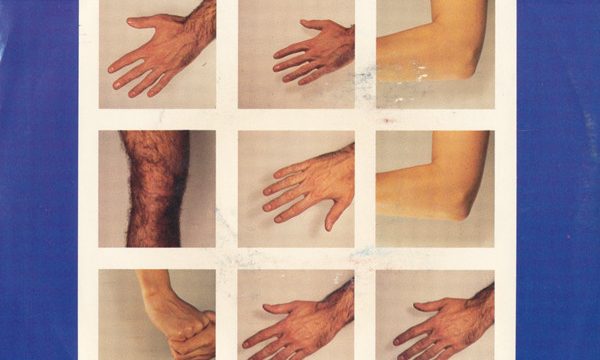

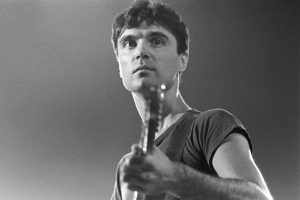

I was first able to converse with the adult world through our shared passion for classic rock. My father kept his music library filled with CDs of Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, Jimi Hendrix, and Janis Joplin, among others, which he would play on repeat. I grew up appreciating the deep emotions that those artists generated within their songs, such that I was always eager to name-drop those musicians in front of any adults I met. Often times my mention of The Police or Yes would be returned with eager nods or reminiscent smiles, except in the case of Talking Heads. The 80s band headed by David Byrne was niche enough to be unknown by most and praised by a certain few, but that didn’t stop me from listening to them. Unlike the other artists I knew, Talking Heads was plainly and unapologetically weird, and that was what got me hooked. As a child, my father and I would flail around to the upbeat syncopation of their songs, and as I got older, my father and I would continue to flail around, just while screaming their nonsensical lyrics at the same time. With album titles like Stop Making Sense and More Songs About Buildings and Food, Talking Heads allowed their listeners to acknowledge the uniformity of everyday life and dance to its pointlessness. So you can imagine my panic when I realized I had to shift the topic of this piece because of Talking Heads’ one and only love song: “This Must Be The Place (Naive Melody).”

What happens when you spend five weeks in a college English class and you suddenly understand the political sentiments of a band that prided itself on not being understood? The answer is, you cry a little bit, you look through your English notes, and then you write about it. With just one love song, I thought that Talking Heads had conformed to Theodor W. Adorno’s theory of “the culture industry,” where all forms of art are produced by capitalist powers to control the political alignment of the masses.¹ It was easy to see the connection: pose as an adventurous rock band with vague musical intentions, gain a following of similarly nonconformist listeners, then BAM! Hit them with a love song that will force them to aspire to settling down and living a life plagued by domesticity. The house that Talking Heads once sang about burning down would now be used to host a complacent, cisgendered, heterosexual couple with a 401k and 2.5 children. Isn’t it devastating?

But don’t worry, I found a way to spin it around, and in order to do so we need to talk some more about Adorno. The mid-20th century philosopher wrote in his essay The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception, that “each single manifestation of the culture industry inescapably reproduces human beings as what the whole has made them. And all its agents, from the producer to the women’s organizations, are on the alert to ensure that the simple reproduction of the mind does not lead on to the expansion of the mind.”² To delve in a bit further, powerful industries such as energy companies use culture as a way of keeping the general public within the confines of capitalism.³ The many different products of the culture industry — movies, art, books, music, and other forms of entertainment — are produced and reproduced so that people become dependent off of the commodities of large corporations. It eventually reaches a point where the human psyche is centered around its products of entertainment: we learn to identify with characters in movies or lyrics in songs such that we want to buy more of the same ideal, and continue giving the “true wielders of power” economic, and thus political compensation.⁴ And this is not a matter of coincidence; these forms of media are carefully crafted and diversified so that their underlying political ideals are easily digestible by the public.⁵ The biggest fear in the culture industry would be “the expansion of the mind,” the aspiration towards nonconformity, such that people would no longer participate in society’s capitalist games.

It is fairly simple to see, then, how traditional love songs promote the political ideals of the culture industry, but it is important to keep in mind that “This Must Be The Place” will differ from the following sentiments. The music of traditional love songs is often slow and sweetly melodical, a formula that makes its listeners feel comfortable with the notion of remaining suspended in time. After being transported into a state of near immobility, listeners can pay special attention to the lyrics of the song, where the real politics of love are voiced. Aspirations of partnership, mutual dependency, and long-term domestic goals are all sung and repeated so that the imagery is ingrained into the mind of the person listening. What tends to not receive as much attention are the social roles and power relations that are simultaneously expressed through these love songs. Take “Love Story,” by Taylor Swift, for example. The song is a retelling of the tale of Romeo and Juliet, implying that there is an aspiration towards a heterosexual relationship between two cisgendered people. The lyric “marry me Juliet you’ll never have to be alone” reflects the goal of remaining solely dependent on a partner until death, otherwise known as marriage.⁶ That lyric is also a command by Romeo that is directed at Juliet, showing that there is a social hierarchy where women must obey the orders of men. In this simplistic love song, the politics of heteronormativity, domesticity, and sexism are disguised as romantic ideals. Within that sphere, the image of a nuclear family appears, with a complacent housewife, a breadwinning husband, and a few mindless children who will grow up to repeat the cycle under the norms of capitalism. Traditional love songs point people towards designated social roles, and most adolescents have already been put under its spell.

It is fairly simple to see, then, how traditional love songs promote the political ideals of the culture industry, but it is important to keep in mind that “This Must Be The Place” will differ from the following sentiments. The music of traditional love songs is often slow and sweetly melodical, a formula that makes its listeners feel comfortable with the notion of remaining suspended in time. After being transported into a state of near immobility, listeners can pay special attention to the lyrics of the song, where the real politics of love are voiced. Aspirations of partnership, mutual dependency, and long-term domestic goals are all sung and repeated so that the imagery is ingrained into the mind of the person listening. What tends to not receive as much attention are the social roles and power relations that are simultaneously expressed through these love songs. Take “Love Story,” by Taylor Swift, for example. The song is a retelling of the tale of Romeo and Juliet, implying that there is an aspiration towards a heterosexual relationship between two cisgendered people. The lyric “marry me Juliet you’ll never have to be alone” reflects the goal of remaining solely dependent on a partner until death, otherwise known as marriage.⁶ That lyric is also a command by Romeo that is directed at Juliet, showing that there is a social hierarchy where women must obey the orders of men. In this simplistic love song, the politics of heteronormativity, domesticity, and sexism are disguised as romantic ideals. Within that sphere, the image of a nuclear family appears, with a complacent housewife, a breadwinning husband, and a few mindless children who will grow up to repeat the cycle under the norms of capitalism. Traditional love songs point people towards designated social roles, and most adolescents have already been put under its spell.

But thankfully, Taylor Swift is not Talking Heads. We can finally return to “This Must Be The Place (Naive Melody)” and pick apart how its changed understanding of love can positively influence people to free themselves from notions of Western domesticity. While the melody of the song is repetitive and reminiscent in the way that most traditional love songs are, there are also tinges of discomfort: the use of multiple synthesizers creates a whining, almost shrieking sound that comes and goes suddenly, and you can hear David Byrne straining his voice with every high note. Although the simplistic style of the song is uncharacteristic of Talking Heads, it is also apologetic: the very title of the song warns the listener that it contains a “naive melody.” The lyrics themselves manage to remain as David Byrne as it gets: riddled with non sequiturs, filled with unanswered questions, and sprinkled with moments of exhausted euphoria. Lines like “I feel numb, born with a weak heart/I guess I must be having fun” reflect how the classic notions of love have made David feel bored and unsure of his own happiness.⁷ For him, love should be as weird and pointless, as sporadic and fleeting as getting hit on the head. Yes, towards the second verse of the song David claims that he’s found home by being with his partner, but he follows with “I guess that this must be the place.”⁸ Even though he has found someone to attach himself to, nothing is certain, and that’s okay. David would rather write that he loves “the passing the time” than another person, and in doing so, he acknowledges that he’s “just an animal looking for a home/[to] share the same space for a minute or two.”⁹ There is no chance for the listener to picture settling down with someone at any point in the song: the lyrics are always ambiguously in motion, where it’s hard to discern a complete sentence or a positive affirmation.

The confusing experience of listening to this song serves to draw a line around political constructions of love and step into the unknown wholeheartedly. “This Must Be The Place (Naive Melody)” exemplifies how Talking Heads manages to parody the traditional form of a love song so that listeners can take comfort in challenging the oppressive institutions that seek to politicize love. Without mentioning ideals of constant companionship and designated familial hierarchies, notions of social roles are pushed so far to the back of the head that the result is “the expansion of the mind,”

the very action that the culture industry seeks to prevent.¹⁰ So I thank David Byrne for his nonconformist politics, and for making me feel okay with achieving a sense of clarity with one of his tunes. The weirdness of his love song makes listeners realize the weirdness of romance and the weirdness of trying to build social hierarchies, asking them to dance with a lamp and “cover up the blank spots.”¹¹

the very action that the culture industry seeks to prevent.¹⁰ So I thank David Byrne for his nonconformist politics, and for making me feel okay with achieving a sense of clarity with one of his tunes. The weirdness of his love song makes listeners realize the weirdness of romance and the weirdness of trying to build social hierarchies, asking them to dance with a lamp and “cover up the blank spots.”¹¹

¹Adorno, Theodor W. Dialectic of Enlightenment: Philosophical Fragments (California: Stanford University Press, 2002), p. 96.

²Adorno, p. 100.

³Adorno, p. 96.

⁴Adorno, p. 96.

⁵Adorno, p. 96.

⁶Swift, Taylor, “Love Story,” in Fearless, Big Machine Records, 2011, http://spotify.com.

⁷Talking Heads, “This Must Be The Place (Naive Melody),” in Speaking in Tongues, Sire, 1983, CD.

⁸Talking Heads, This Must Be The Place (Naive Melody), CD.

⁹Talking Heads, This Must Be The Place (Naive Melody), CD.

¹⁰Adorno, p. 100.

¹¹Talking Heads, This Must Be The Place (Naive Melody), CD.