Rats, Restaurants, and Stealing from Poor People

I have seen the movie Ratatouille an absurd number of times. My family only had one movie on DVD when I was growing up and it just so happened to be Ratatouille. I have seen this movie so many times that I could probably regurgitate the entire script word for word onto this piece of paper. Every single time I watched this movie as a child I assumed it was just about a rat who wanted to be a chef. And at face value, that’s what it seems like; just another animated Disney movie with talking animals that act like humans. But Ratatouille isn’t really about rats. Ratatouille is the struggles and hopes of working class people molded into a personified animal, packaged into DVDs, and resold to the very people it emulates.

Remy, the main character of Ratatouille, is poor. We know this because he lives by an old farmhouse in the countryside and literally eats trash. Remy is also the rat version of a foodie, and it becomes very apparent early on in the movie that he is miserable with his life as a garbage sorter. His dream is to move to Paris and become a chef, a dream which his father is unsupportive of. Remy’s father says things like “we’re rats, we don’t cook” and “shut up and eat your garbage” with the same tone that you would expect to hear from a father who just found out his son wants to quit the football team and go to art school. Remy is swept away to Paris, where he stumbles upon the kitchen of the city’s most renowned restaurant, Gusteau’s, and befriends the restaurant’s garbage boy, Linguini. Although Linguini is the nephew of the founder of Gusteau’s, he is a talentless cook and has thus been demoted to lowest possible ranking on the totem pole of the kitchen. Remy begins teaching Linguini cooking in secret and they work together to prove themselves in the hierarchical world of fine cuisine. On the night that a leading food critic, Antoine Ego, is set to dine at Gusteau’s, Linguini reveals that the mastermind behind his success is a rat and the rest of the cooking staff quits. Remy then mobilizes a workforce of his rodent brethren to run the kitchen and save Linguini’s family’s restaurant. Remy and Linguini cook ratatouille for Ego, which reminds him of his childhood and leads to him writing a glowing review for the restaurant.

Sure, this may just seem like another heartwarming Disney film where the main character beats the odds and achieves their dreams. But what the film really does is take the culture of the rural poor and romanticize it by adding talking animals and a seemingly peaceful ending. By looking at the very opening scenes of the movie, which show the rats living near a French cottage in a rural area, we can establish that Remy is supposed to represent a peasant. Remy’s desire to become a chef is therefore hindered by his social status as a peasant. Remy’s father emphasizes the rigidity of these social classes and the lack of upward mobility for peasants when he reminds Remy of the futileness of these dreams. It is not a mere coincidence that the namesake dish of the movie, Ratatouille, is traditionally a French peasant’s dish. It should also not go without note that the director of Ratatouille, Brad Bird, was born in rural Montana, developed an early passion for animation, and moved to California at a young age to pursue a job in the film industry, a strikingly similar journey to that of Remy’s.

The problem that Remy faces with achieving his dream job as a chef is not that he lacks the skill to cook, but that the urban elite that dominates the restaurant industry won’t accept him because of his status. This is emblematic of the class-based discrimination that the working poor face. Rural poor are often viewed as “simple” and their skills and talents are overlooked simply due to their social class. The film takes this prejudice against the rural poor and makes the audience see it as simply not wanting a rat in your kitchen.

This brings us to the director’s decision to include the friendship between Remy and Linguini. While Remy is representative of the rural working poor, Linguini is representative of the urban working poor. He performs skill-less labor as the restaurants trash boy, mopping the floors and taking out garbage. However, as nephew of the restaurant’s founder, Linguini has ties to the industry elite. This means that if Remy is able to masquerade his cooking talent as Linguini’s, it will be accepted by the food critics who play such a decisive role in deciding what does and doesn’t count as good cooking. It is this collaboration that gives us all the iconic Ratatouille scenes of Remy guiding Linguini by pulling on his strands of hair like a life-size, flesh and blood marionette.

But what does the entire kitchen staff do when they find out that Linguini can’t actually cook and the mastermind behind all his dishes is a rat? They quit. Because who in their right mind would work at a kitchen where the head chef is a rat. No amount of Disney magic can hide the fact that skilled professionals would rather walk away from their jobs than work for a peasant.

At this point the movie takes an interesting turn. Remy turns to his rat colony and convinces them to come help him out and work in the kitchen of the restaurant. He divides the rats into several crews and assigns each crew to a various jobs in the kitchen. The next scene shows a bustling kitchen with rats performing every job from slicing vegetables to stirring pots to loading plates as Remy shouts out orders. It is a scene oddly reminiscent of a factory, only the good being produced is food. And with this, Remy has achieved what many peasants can only dream of. He has gone from sorting garbage at a farm in rural France to running a factory in the heart of Paris, a leap in status that few achieve. This aspect of the film builds on the aspiration of many rural working class people to move to the city and find a better job.

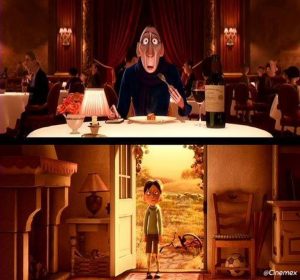

When Antoine Ego arrives at Gusteau’s to review the restaurant, Remy decides to serve him ratatouille. Ego seems skeptical of the dish but with the first bite his eyes open wide and the movie cuts to a flashback. A young Antoine stands in the front door of his home in the countryside with a bloody knee and a hurt expression. His mother serves him a plate of ratatouille, his expression lights up, and the flashback is over. Thank you, Disney, for reminding us that we like home-cooked meals. Apparently all it takes to win over the biggest food critic in France is to serve them a homestyle meal with a side of nostalgia. All the film does here is appropriate the dish ratatouille from French peasant culture and rebrand it as a dish that is served to the top food critic in the highest of restaurants.

Following this scene, Antoine demands to meet the chef and and Linguini explains the entire situation to him. Antoine is taken aback but the next day he writes a glowing review for the restaurant, saying that “a good cook can come from anyone” as a subtle nod to Remy. It is clear that Remy, a lowly rat from the country, has completely changed Antoine’s perspective on cuisine. But Antoine is only one person. And what does the upper class do when a lower class person revolutionizes something that could undermine them? They put them back in their place. Sure enough, the former head cook reports the restaurant for health code violations because it is, after all, being run by sewer rats. In the end, it is still the hierarchy of chefs that comes out on top, not the peasant from the countryside. Remy has to forfeit his dream of being the top chef in Paris and instead is forced to remain hidden under the hat of Linguini. Sure, Linguini opens a new restaurant where Remy can work in private, but he must remain hidden because the cooking community would still be horrified to find out that a peasant is running a restaurant.

Jeffrey Fleishman of the LA times claims that Hollywood is out of touch with the working class, that it doesn’t portray them accurately. And he’s right. Pop culture takes what it wants from working class culture and changes it to fit its own functions and meanings. Ratatouille is no longer a food of French peasants, it is an expensive dish in a fancy restaurant. Hollywood instead presents to working class people a twisted version of their own culture, one that doesn’t resemble them exactly but is built on the idea of their culture.

Ratatouille is less about a rat that wants to become a chef and more about the struggles, hopes, and culture of the rural poor. The struggle to have your talents be seen as valid by those in the professional sphere. The hope of being able to get off the farm and find a job doing something you love in the big city. The struggle to get your family to accept that you want to pursue a job outside the normal career choices for someone of your class. And, of course, the power of a home-cooked meal. As one essayist puts it: “even music that expresses some working class values is a commodity enterprise.” This holds true to film as well. Hollywood films like Ratatouille express a twisted form of working class culture, but do so only to earn a profit from their audience, much of whom is working class. Pop culture steals the identity ordinary people, modifies it, and sells it right back to them.

Bibliography

Miller, Arthur J. “Working Class Culture.” IWW Historical Archives, Industrial Workers of the World, www.iww.org/history/library/AJMiller/Working_Class_Culture.

Fleishman, Jeffrey. “Realism or Cliche? Hollywood Struggles to Get the Working Class Right – Los Angeles Times.” Los Angeles Times, Los Angeles Times, 7 Jan. 2017, beta.latimes.com/entertainment/la-et-hollywood-values-updates-realism-or-stereotype-hollywood-has-a-1483646040-htmlstory.html