For a long time, I have tried to explain the momentary discomfort I felt from time to time upon seeing the media’s version of an “Asian culture” for the first time. I vaguely imagined that I was offended, but at the same time I had doubts about the validity of my own feeling, that felt rather foreign. The pop industry’s claim about Asian culture–despite their tendency to confuse Chinese, Japanese and Korean cultures–usually has a grain of truth. The celebrities did wear what appeared to be some Asian countries’ traditional costume, the martial arts indeed is an East Asian cultural artifact, and I was not a qualified cultural expert to pinpoint some minor details they may have gotten wrong. Before I finally found out the true source of my unease hidden behind a few factual inaccuracies–an unfamiliarity behind a familiarity–I was cautious not to appear overly sensitive and tried to believe that what I was witnessing was an interaction among different cultures. People’s dismissive attitude about cultural appropriation, in this context, is not hard to understand. A white narrator from TheRebel Media explains one should stop “whining about cultural appropriation” because wearing a foreign costume does not take away anything from the original culture, and she herself wore a kimono to a japanese festival without offending anyone. I believe it was essentially a similar sentiment that inspired Erika Christakis, a former Yale lecturer who urged her students to “be a little obnoxious..a little bit inappropriate or provocative or…offensive” in their choice of Halloween costumes. From the perspective of a child development educator, she saw indirect contact with the foreign as “transgressive”. Bell Hooks might call this desire for a personal transcendence a cultural cannibalism, readily consuming the culture and the history of the Others for one’s use (Hooks, 2001). But Christakis would doubt if wearing your favorite costume–just as she herself bought a Bangladesh clothes in a local market–brings such grave effects.

I am not giving all these claims from proponents of cultural appropriation to say they are wrong. It is simply superficial to think that only things that can be appropriated are things with forms, such as clothes, accessories, food recipes etc. Frankly, the products themselves are of secondary importance. I am aware that Katy Perry’s special performance of her new release Unconditionally in American Music Award 2013 roused controversy mostly because she was white, and she was wearing a traditional Japanese costume. She used a Japanese costume to perform in front of her white audience, and some critics found it appropriative. And my argument starts here: it is not the apparent visual discrepancy that makes her performance a blatant example of cultural appropriation. It is not the reason people should care at all about a pop industry appropriating a culture. The discussion of cultural appropriation should instead focus on the hidden idea wrapped in the visual.

It is not to say that the visual aspect of the performance is irrelevant. It seems that Perry confused traditional Chinese clothes with Japanese clothes in her delivery of Japanese cultural artifact.

Overall pattern and style of the costume appears to be kimono, but the neck and open slits resemble cheongsam, a traditional Chinese costume. What she gives her audience is the general feel of East Asia, nonspecific and generalized, while claiming to represent one specific culture. Kimono is a costume a Japanese person would wear to funerals, festivals, coming-of-age ceremonies, or on any other ceremonial occasions. It is a quintessential symbol of Japan that people “hold it to their heart” (Valk, 2015). Nonetheless, this very item is now tailored to fit into Perry’s marketed image. With the open chest and sides that reveal Perry’s legs, kimono now is an outfit for a free spirited and hot California “gurl” who sings in her powerful voice.

Overall pattern and style of the costume appears to be kimono, but the neck and open slits resemble cheongsam, a traditional Chinese costume. What she gives her audience is the general feel of East Asia, nonspecific and generalized, while claiming to represent one specific culture. Kimono is a costume a Japanese person would wear to funerals, festivals, coming-of-age ceremonies, or on any other ceremonial occasions. It is a quintessential symbol of Japan that people “hold it to their heart” (Valk, 2015). Nonetheless, this very item is now tailored to fit into Perry’s marketed image. With the open chest and sides that reveal Perry’s legs, kimono now is an outfit for a free spirited and hot California “gurl” who sings in her powerful voice.

Traditional Cheongsam

Traditional Kimono

Kimono is a costume a Japanese person would wear to funerals, festivals, coming-of-age ceremonies, or on any other ceremonial occasions. It is a quintessential symbol of Japan that people “hold it to their heart” (Valk, 2015). Nonetheless, this very item is now tailored to fit into Perry’s marketed image. With the open chest and sides that reveal Perry’s legs, kimono now is an outfit for a free spirited and hot California “gurl” who sings in her powerful voice. Nonetheless, I have to say that it is worth pointing out Perry’s inaccurate representation but such analysis does not touch the heart of the issue. Yet even critics these days end their analysis on what they can see. Their analysis is shallow, trite, and insignificant. Patricia Park, a writer of New York Times and Guardian, expresses her confusion in her editorial:

“Her kimono, despite some cultural inaccuracies in the form of strategic slits, was rather prim by Hollywood standards. (…) I couldn’t find anything that officially screamed offensive … And there have been far more egregious “yellow faced” attempts.”

Park adds that she as an Asian American is rather indifferent to her choice of clothes, and so were the most of Asian American students to whom she gave lectures about culture. Park’s analysis is noteworthy for two reasons. First, even the language of a cultural critic focuses on visual aspects of the performance. What she assumes in her argument is that if Perry wore traditional kimono and cultural experts confirmed everything they saw was right, there should be no problem. Park only succeeds in analyzing a piece of cotton, not the context in which it is placed –which I will discuss soon. Second, she emphasizes her Asian American ethnic identity to give her voice more depth and authority than it deserves. And Park is not the only one. In Perry’s performance, Just like many other talks about cultural appropriation, one’s ethnic identity appears to be an ID card one shows to enter the discussion forum about Perry’s performance. A frequent reference to one’s ethnic identity and origin in this sort of discussions is an appeal to one’s historic lineage rather than one’s knowledge in the subject matter. It is inherently given, not earned. It is just like an unalienable right – a right to freedom, a right to happiness–except that it is a right reserved for only a select number of people. I call it a ‘right to be offended.’ And this right, directly or indirectly called for in the public discourse surrounding Perry’s performance, decides whose voice is to be heard and whose is to be discarded.

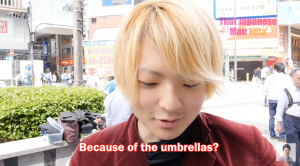

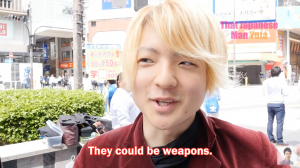

It is the conversation between the appropriator and the appropriated, the offender and the offended. People who are in neither of the category are cautious, unsure, and silent. One Japanese commented online expressed what appeared to be a general confusion at the apparent “fuss”: “I’m Japanese and I appreciate she expressed the beauty of Japan and its culture. Everyone is unnecessarily nervous on cultural issues.” Some tried to argue that Perry’s performance was problematic and offensive, to which an anonymous commentator replied: “Are you Japanese?” With the right to be offended as the ultimate authority, the public discourse about Perry’s controversy is bound to be dichotomous. There is only one Japan and one Foreign. In the past, it was a similar division that led the West to treat the Eastern counties and their culture as one collective entity, the Orient, and decorate it with their fantasies (Said, 1987). And even in the present, the seemingly productive discussion on culture is caught up in generalization, stereotypes, and deindividualization. One well-received Youtube video “Can Foreigners Wear Kimono? (Japanese Opinion Interview)” by a Japanese cultural writer shows how this works. Two entities –“Foreigners” and “Japanese” – have conversations about cultural appropriation, while all the others are spectators. Himself a Japanese, he and his interviewees found no problem with Perry’s performance. To confirm this claim, he put representative authority on seven Japanese people, whose name, age, background etc. remained unknown. It was this precise vagueness that seemed to give those voices a license to speak on behalf of the Japanese. One can only speculate from their causal outfits that they are probably ordinary young people, perhaps college students. Filling the void of their individualities, are their Japanese faces, the language, and their presence in a street of Japan. One interviewee speculated why Perry’s performance might have been criticized: “Because of the umbrellas? They could be weapons.”

This Japanese Youtuber who profits from his production, does what the business of appropriation is accused of doing. He asks the audience to take a generalized imagery associated with Japan, perhaps with the touch of childlike innocence of the East and appreciation to the West, as ordinary experiences of the Japanese. The audience willingly does, disarmed by the license of cultural identity.

So far, I have given most attention to the reception of Perry’s performance, and now I move to direct my attention to the content and the idea behind her work–the point a conversation about cultural appropriation should focus on. Anyone who has watched the music video of Perry’s Unconditionally –and here she does not wear kimono but a dress in a ballroom – can see that her message is simple and straightforward. The images of a mother holding her child, affectionate gestures between lovers of different race and even gender show Perry’s emphasis on the love that transcends limitations.

A car crashing into Perry in the music video almost reinforces the idea of self-sacrifice. In Perry’s AMA performance, she embodied this embracing and almost self destructive love through a body of japanese geisha. The nuance and the visual association Perry draws in her performance reminds one of a fictional character “ChoCho San” from Madame Butterfly. ChoCho San first appeared in a short story written by an American writer in 1898, a period after the year 1853 when Japan was forced to open its port to the West. Later in 1904, this piece turned into Puccini’s opera in 1904. ChoCho San is a geisha who falls in love with white lieutenant, waits for him everyday, and kills herself when she is abandoned. At that time, an affair between a Japanese woman and a white visitor was not unheard of. But the portrayal of ChoCho San is only complete with a Western fantasy about an unconditional love of an Asian woman. Un bel dì vedremo (“One fine day we shall see”) shows ChoCho San’s endless waiting:

And I wait a long time

but I do not grow weary of the long wait.

(…)

I with secure faith wait for him.

And in her performance, Perry brings back the idea from more than hundred years ago and sings of unconditional love just like ChoCho San would do. She sings of “All your insecurities / All the dirty laundry” that she readily embraces while she is dancing in a kimono. She sings of a love that can, as shown in her music video, bring her own destruction while she shows herself surrounded by japanese cultural artifacts.

Perry’s AMA performance

ChoCho San from Madame Butterfly

Many follow-up articles on the performance said the staging was exotic – “originating in a distant foreign”. The very idea is constructed upon the notion of distance, but not a physical distance in this context. It is a distance between time, between a modern and postcolonial, between the present and the past. Even in the year 2013, the image of Japan is still trapped in the late 1890s when Japan was first penetrated by the West. This is the idea of Japanese culture wrapped in kimono, flower blossoms, and extravagant paper fans. And Perry returns this newly crafted culture to not only her white audience but also to the Japaneses. In all her innocence, Perry said her performance was meant to pay tribute to Japanese culture, and clarified that she did not mean to mock their culture at all. It was her love that led to the production of this particular performance. The crucial question at this point is – does intention still matter? Perry has the product of cultural appropriation up on stage, people have seen it, and it’s there. I say what matters is the invisible idea that the images hide, an imaginary fantasy about the Others that the consumers are asked to believe as a reality. Changing the content and returning it in the same wrapper is the industry of appropriation.

Emulated the style of George Orwell (“Why I Write”), revised by Aanya Kupur, in response to the prompt about cultural appropriation of ordinary people.

Reference

Park, Patricia. “Why all the fuss over Katy Perry’s geisha performance at the AMAs?”, The Guardian, November 26th 2013, Web.

Rebel Media, “Cultural appropriation isn’t racist–it’s really cultural appreciation”, Rebel Media, September 21st 2015, Web. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VwQvnyIR9_0

Said, Edward. “Orientalism”, Pantheon Books, 1978. Print.

Valk, Julie. “The “Kimono Wednesday” Protests: Identity Politics and How the Kimono Became More Than Japanese”, Asian Ethnology Vol 74 No.2, 2015, Web.

Yuta, “Can Foreigners Wear Kimono (Japanese Opinion Interview)”, That Japanese Man Yuta, September 26th 2016, Web. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0pXotxxYFlk