James Bond is the archetypical, suave, muscular, witty hero, who many guys only dream of becoming. He saves the day, gets the girl, beats up or kills a few baddies along the way. The 2006 reboot of the Bond franchise, in Casino Royale, depicts Bond (played by Daniel Craig) as an impulsive, yet clever, assassin, who lets his actions speak louder than his words. Craig’s character is not nearly as sexed up as his Bond predecessors, but he compensates with his brawn and brutishness. This is one of many subtle, but also drastic changes that the franchise has taken in the reboot. Historically, previous Bond films have been highly sexist and materialistic, portraying Bond as a comedic, likeable guy, who always seduces a beautiful woman, half his age. In Casino Royale, the story takes a modern twist, casting the woman (Vesper Lynd) on a progression towards the dominant role, and Bond on a path towards an emasculated shell of a man. The film goes against conventional Hollywood norms, initially portraying either character in their gender’s negative stereotypical fashion, subsequently sending Vesper to ascendancy and Bond to inferiority. Bond is castrated, and Vesper washed of her womanhood.

Until we get to the heart of the film, the casino locale in Montenegro, Bond is depicted as a ruthless, cold-blooded killer with few to no redeeming values. He gets his job done by being a high-testosterone, stereotypical male with a drinking problem. The opening scene is a pursuit, Bond chasing a bomb-maker across cranes, several hundred feet in the air, smashing through walls, exhibiting his crude, brute-strength (Amacker, Moore 145). He acts before he thinks, causing a shootout at an embassy, killing a man across international borders, etc. If anything, Bond is painted as an impulsive killer—like an abusive husband, he engages in violence without thoughts of repercussions. Mark Worrell and Daniel Krier recognize that, “Craig’s Bond was emotionally-detached,” depicted as a “cold, ascetic soldierly-male” (8). They go on to explain that Craig’s Bond was more focused on physically beating his enemies, taking each victim as an end, rather than a means to an end. For the new Bond, politics were unimportant; the mission was the target. Restating what I mentioned earlier, in Casino Royale, Bond is coarse and blunt, fitting the mold of the negative stereotypical male (i.e. physically aggressive). I need not mention his alcohol addiction problem, which further typifies him as a wife-beater.

Contrastingly, Vesper is initially depicted as delicate and stereotypically feminine. She readily bends to Bond’s will, dressing in a scandalous dress, subsequently approaching Bond at the poker table, and seductively kissing him. Essentially, her major role in the first chapter at the casino is to be a trophy to show off to the rest of the room. Vesper ceases to be human, in the sense that her purpose becomes more of an objectified, material intimidation. Furthering her stereotypical feminine inferiority, when Bond goes all macho, and kills the Ugandan warlord and his accomplice (with his bare hands at that), Vesper goes into shock. She breaks down into tears, like a damsel in distress. Clearly either character fits the mold of their negative gender stereotypes. Vesper is objectified, and any attempt of hers to be something more just causes additional problems. Bond is presented as callous, physical, and impulsive, and, more often than not, it is his stubbornness that gets him into greater trouble.

Contrastingly, Vesper is initially depicted as delicate and stereotypically feminine. She readily bends to Bond’s will, dressing in a scandalous dress, subsequently approaching Bond at the poker table, and seductively kissing him. Essentially, her major role in the first chapter at the casino is to be a trophy to show off to the rest of the room. Vesper ceases to be human, in the sense that her purpose becomes more of an objectified, material intimidation. Furthering her stereotypical feminine inferiority, when Bond goes all macho, and kills the Ugandan warlord and his accomplice (with his bare hands at that), Vesper goes into shock. She breaks down into tears, like a damsel in distress. Clearly either character fits the mold of their negative gender stereotypes. Vesper is objectified, and any attempt of hers to be something more just causes additional problems. Bond is presented as callous, physical, and impulsive, and, more often than not, it is his stubbornness that gets him into greater trouble.

Following Vesper’s break-down over the bodies of the Ugandan militants, there is some progression in gender roles. Bond showers Vesper in order to wash her blood stained skin. The scene is highly symbolic, showing Vesper washed of her womanhood. Bond, in a sense, baptizes her. By cleaning her of her “weaker feminine qualities,” Vesper becomes more pure and capable. This is not to be confused with Vesper’s progression to masculinity. On the contrary, she is stripped of her negative, feminine stereotypes. Having been washed of her “menstrual inferiority,” we immediately see a change in Vesper’s character. Bond is poisoned by the antagonist’s girlfriend, and is unable to deal with his condition before passing out. Out of nowhere, Vesper comes to the rescue, fixes the defibrillator, and saves Bond’s life. In a matter of a couple scenes, Vesper goes from helpless damsel to hero. To a certain degree there is a role reversal, wherein Bond actually becomes the dependent damsel in distress.

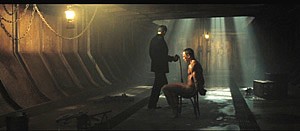

Bond’s progression to emasculation reaches its climax when he is symbolically castrated. Near the end of the film, Le Chiffre (the film’s antagonist) repeatedly swings a weighted, knotted rope at Bond’s manhood as Bond sits, strapped naked to a chair. The scene is very sexed up, suggestively insinuating that Bond is getting raped. Two distinct shots show Le Chiffre dangling the knotted rope between his own legs, and then laying the rope across Bond’s chest, much like a phallic symbol (Amacker, Moore 146). It becomes increasingly evident that Bond is being castrated, and therefore emasculated, when Le Chiffre makes the comment, “there will be little to identify you as a man.” Before the scene comes to a close, Le Chiffre threatens to feed Bond his manhood, an act of fellatio, utterly effeminizing whatever sense of masculinity he has left.

Vesper, again, saves the day, striking a business-like deal with Le Chiffre’s killers, offering them money in exchange for her and Bond’s lives. Bond passes out as Vesper organizes their salvation, consummating his transition to fragility, and Vesper’s transition to fearlessness and independence. The relationship between bond and Vesper continues, after Bond wakes in a hospital in Venice. It is important to note that Vesper continues to assume all dominant roles, commonly associated with men in Hollywood films. Vesper initiates sex, asserting her dominance over the fragile, weakened Bond. Bond has fallen in love, embracing emotions, which were not central to his character earlier in the film. Furthermore, Bond, having resigned from his 00 status at MI-6, realizes he cannot hold an “honest job,” because he “has no idea what an honest job is” (147). His dependence on Vesper will continue. Symbolically castrated, and without his job, which, for that matter, allows him to assert his dominance, Bond becomes reliant on Vesper to care for him. He confesses to Vesper, “I have no armor left. You’ve stripped it from me.” Disarmed, disengaged, and jobless, whereas Bond was once a symbol of power and security, he now stands as a symbol of emotion and care.

We see Bond’s changed self in his failure to save Vesper, drowning in an elevator shaft. Whereas early-on in the movie we would have thought Bond would have no problem busting open a metal gate, by the end of the film, we know his emasculated self is nowhere strong enough to save the one he loves. Furthermore, his new-found emotions further disparage his mind from the inside. Neither physically nor mentally strong, Bond is thrown into despair.

Vesper reaches her full ascendancy by deceiving Bond. She has “grown the balls” to not only cheat behind his back (i.e. have a husband without him knowing, and strike a deal without him knowing), but she also has the guts to physically take her own life. She puts herself in a metal cage, like a diver swimming with sharks, protecting herself, isolating herself from the patriarchy. Vesper maintains her independence through the end. She doesn’t, however, take on the role of a male figure. Although she adopts dominant roles and attributions, she maintains her femininity, in a more independent manner. Unlike common Hollywood gender transitions, Vesper doesn’t become brutish and manly, rather, she preserves her beauty and wit from earlier on in the film. By her end, it becomes apparent that she has reached a level of dominance, and Bond has succumbed to impotence.

The argument could be made that, contrary to my thesis, Bond bounces back and regains his manhood, and, furthermore, the film as a whole suppresses women. For the latter matter, Amacker and Moore both conclude that, “Casino Royale…does more to undermine the status of women than any of the previous incarnations of Bond” (144). Such a statement is not easy to brush off in a matter of a few hundred words, assuming that my argument thus far has not already proven it otherwise. The reality is that Bond doesn’t bounce back. Having been effeminized, in his castration he faces a large degree of penis envy. After Vesper deceives him, he feels an obligation to compensate for the loss of his endowment. Even to this extent, when Bond pursues Vesper and her clients to the Venetian mansion, he both literally and figuratively gets nailed. One of the henchmen shoots a nail into Bond from behind, in one sense of the term or another, penetrating him. Bond, further emasculated, goes into a fit of rage, attempting to make up for his lost dignity. The film closes with Bond shooting one of Vesper’s clients in a sad attempt to regain his manhood, a task he knows is undoable. Bond approaches his target clutching a large gun, a phallic object, in an erect position. Bond’s insecurity is unmistakeable. If anything, Casino Royale undermines stereotypical gender roles, particularly going against those portrayed in past 007 films.

Erected? Unlikely.

The Bond reboot discredits the common belief that Hollywood films are patriarchal. Casino Royale portrays both genders in their negative stereotypical fashions, but then puts either gender on tracks to transcend their norms. Femininity, represented by Vesper, ascends to independence and other qualities often associated with masculinity, whereas masculinity, represented by Bond, is effeminized. It is important to note, however, that Vesper does not come to represent masculinity, rather, she comes to adopt roles and qualities that men often exercise (i.e. business transactions, cheating, deception, financial independence, sexual instigations, etc). We see character transitions, when Vesper is washed of her womanhood (that is, when Bond washes the blood from her hands), and when Bond is tortured (or symbolically castrated). The film seems to reestablish norms by breaking the attributes that are hermetically sealed with either gender. Women can still be beautiful and emotional without succumbing to dependence and frailty. Men, on the other hand, can just as easily be emasculated, or in Bond’s case, castrated.

Works Cited

Amacker, Anna Katherine, and Donna Ashley Moore. “’The Bitch is Dead’: Anti-Feminist Rhetoric in Casino Royale.“ James Bond in World and Popular Culture: The Films Are Not Enough. Ed. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars, 2011. E-Book.

Worrell, Mark P., and Daniel Krier. “The Imperial Eye.” The Imperial Eye. Fact Capitalism. Web. 16 May 2016.