If you are one of the three in ten Americans who believes that the Bible must be taken literally (Gallup), I should warn you that this essay will call your conviction into question—but not for the typical reasons. Countless researchers have disproven “strict creationism”—the notion that God created the earth and all its creatures in their present forms in six days—through such techniques as radioactive dating and evolutionary analysis, but often creationists simply reply that those techniques must be flawed; after all, the creation of the universe is laid out clearly and explicitly in the Bible. I will argue on those terms: not that creationism is scientifically invalid, but that it is biblically invalid.

If you are one of the three in ten Americans who believes that the Bible must be taken literally (Gallup), I should warn you that this essay will call your conviction into question—but not for the typical reasons. Countless researchers have disproven “strict creationism”—the notion that God created the earth and all its creatures in their present forms in six days—through such techniques as radioactive dating and evolutionary analysis, but often creationists simply reply that those techniques must be flawed; after all, the creation of the universe is laid out clearly and explicitly in the Bible. I will argue on those terms: not that creationism is scientifically invalid, but that it is biblically invalid.

This may sound like an outrageous claim, but read the Judeo-Christian creation narrative closely and one will find not just that it should not be read literally but that it cannot be read literally, that the story is in fact incoherent and unintelligible: the famous first sentence is a hopeless grammatical nightmare; sequencing the creative events is impossible; and there are in fact two distinct creation narratives, one after the other, that prove irreconcilable despite scholars’ greatest efforts. Indeed, the number of days of creation isn’t even certain. If you believe that God created the world, the last thing you should do is pick up a Bible—and to see one reason why, we need look no further than the very first word.

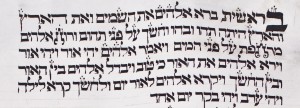

It is popularly known that according to Genesis, God created the world “in the beginning” (בְּרֵאשִׁית, b’reishit), but this is not in fact what the first word of the Bible means. “The,” first of all, is nowhere to be found in the text: בְּ (b’) means “in,” but the definite article (הַ) is lacking—b’reishit instead of b’hareishit—and though biblical poetry occasionally omits definite articles, expecting the reader to fill them in, biblical prose never does. This prompts a translation of “In a beginning,” which in turn raises all manner of questions: Are there multiple beginnings to this world? Are there multiple worlds? If so, did our God create those too? But this translation is not quite correct either, for if it were, the text would have read bareishit, changing the vowel underneath the בּ from בְּ to בָּ. With this particular vowel, b’reishit means “in the beginning of,” requiring a noun after it—there are four other places in the Torah where it does so and none where it does not (Genesis, 1.1; Reb Jeff)—but the next word in the sentence, problematically, is not a noun but a verb: בָּרָא (bara), meaning “created.” A literal translation, then, of the first two Hebrew words in Genesis would read, “In a beginning of God created”—in other words, an “ungrammatical mess” (Reb Jeff). Most modern “literal” translations approximate the Hebrew as “In the beginning of God’s creation” or “In the beginning of God creating”; this still proves inadequate since בָּרָא is neither a noun nor a gerund (Goodheart and Osborne), but if a translator seizes this approach, interestingly enough, Genesis 1-3 could be one large sentence, as punctuation was only added by the early Christians. One such translation: “When God began to create the heavens and the earth, the earth being formless and void, darkness upon the face of the deep, and the breath of God hovering upon the face of the waters, God said, ‘Let there be light’: and there was light” (Giere, 18).

It is popularly known that according to Genesis, God created the world “in the beginning” (בְּרֵאשִׁית, b’reishit), but this is not in fact what the first word of the Bible means. “The,” first of all, is nowhere to be found in the text: בְּ (b’) means “in,” but the definite article (הַ) is lacking—b’reishit instead of b’hareishit—and though biblical poetry occasionally omits definite articles, expecting the reader to fill them in, biblical prose never does. This prompts a translation of “In a beginning,” which in turn raises all manner of questions: Are there multiple beginnings to this world? Are there multiple worlds? If so, did our God create those too? But this translation is not quite correct either, for if it were, the text would have read bareishit, changing the vowel underneath the בּ from בְּ to בָּ. With this particular vowel, b’reishit means “in the beginning of,” requiring a noun after it—there are four other places in the Torah where it does so and none where it does not (Genesis, 1.1; Reb Jeff)—but the next word in the sentence, problematically, is not a noun but a verb: בָּרָא (bara), meaning “created.” A literal translation, then, of the first two Hebrew words in Genesis would read, “In a beginning of God created”—in other words, an “ungrammatical mess” (Reb Jeff). Most modern “literal” translations approximate the Hebrew as “In the beginning of God’s creation” or “In the beginning of God creating”; this still proves inadequate since בָּרָא is neither a noun nor a gerund (Goodheart and Osborne), but if a translator seizes this approach, interestingly enough, Genesis 1-3 could be one large sentence, as punctuation was only added by the early Christians. One such translation: “When God began to create the heavens and the earth, the earth being formless and void, darkness upon the face of the deep, and the breath of God hovering upon the face of the waters, God said, ‘Let there be light’: and there was light” (Giere, 18).

In the face of such opacity as the first few words of Genesis, what are readers to conclude? We may call that vowel a mistake, but those who believe that God dictated those words and that “Nothing is here by chance” will no doubt resist that interpretation (van Kooten, 5); or, alternately, we can reach for a super-grammatical meaning, such as, “The world was created, but it never stopped being created. The world has a beginning, but it is a beginning that has never ceased” (Reb Jeff). This, of course, is not the literal interpretation three out of ten Americans demand, but those readers fail to realize that “the ambiguity is inherent in the text itself”: no literal exegesis is possible (Giere, 20).

In the face of such opacity as the first few words of Genesis, what are readers to conclude? We may call that vowel a mistake, but those who believe that God dictated those words and that “Nothing is here by chance” will no doubt resist that interpretation (van Kooten, 5); or, alternately, we can reach for a super-grammatical meaning, such as, “The world was created, but it never stopped being created. The world has a beginning, but it is a beginning that has never ceased” (Reb Jeff). This, of course, is not the literal interpretation three out of ten Americans demand, but those readers fail to realize that “the ambiguity is inherent in the text itself”: no literal exegesis is possible (Giere, 20).

The enigma presented by the rest of the creation story is not that it is ambiguous but that it is quite unambiguous—and yet the two chapters are clearly contradictory. In Genesis 1, creation takes place over six days, and plants are created first, then animals, then man and woman: “male and female He created them” (Genesis, 1.27). Turn the scroll to Genesis 2, however, and suddenly the creation narrative changes. It begins, “These are the generations of the heavens and of the earth when they were created, in the day that the Lord God made earth and heaven” (Genesis, 2.4). Suddenly all of creation has taken place in one day, not six. Not only that, but the sequence has changed: man is created before plants and animals, and it specifically states that before man “no tree of the field was yet on the earth, neither did any herb of the field yet grow, because…there was no man to work the soil” (Genesis, 2.5). Only after all else is woman created, as an afterthought, and she is formed in a different way from man: while for man God “breathed into his nostrils the soul of life,” God shaped woman from one of man’s ribs (Genesis, 2.7, 2.21-22). These contradictions have profound implications for environmental ethics and gender dynamics, for if the natural world were created for man (if he were created first, if nothing could grow without him, if he named the animals), then at least some level of exploitation must be expected; and if woman were created not only after man but out of man, another step removed from divine breath, gender inequality might be justified in religious terms.

Many scholars have attempted to reconcile these two competing narratives. Rashi insists that “The listener may think that this is another story, but it is only a detailed account of the former,” which doesn’t at all explain the contradictory orders and number of days (Genesis, 2.8). As for the discrepancy in sequencing, he teaches that “everything was created on the first” day but was “brought forth” on different days: for example, plants were created on the third day as the first version requires, but “they stood at the entrance of the ground until the sixth day,” after man was created (Genesis, 1.24, 2.5). Though this explanation takes the liberty to add midrashically to the text, it is at least plausible, but it nonetheless fails to account for the second version’s claim that creation was only one day long. As for how male and female were created, Rashi suggests, “He originally created [man] with two faces, and afterwards, He divided him” (Genesis, 1.27); other scholars expound: “In the first story of creation (Gen 1:27) an androgyne is made by Elohim. In the second account of creation, YHWH Elohim separates man and woman by creating Eve (Gen 2:18). Now the androgyne is split up into two distinctive creatures, a male and a female” (Luttikhuizen, 4). Dividing a hermaphrodite in half, however, is quite different from creating man and then extracting a single rib to form woman; thus, this interpretation neglects the clarity and specificity of the second account. In the creation story, “inconsistencies and contradictions…come down to us as a single work” (Brichto, viii)—so when someone identifies as a creationist, it begs the question: which version?

Many scholars have attempted to reconcile these two competing narratives. Rashi insists that “The listener may think that this is another story, but it is only a detailed account of the former,” which doesn’t at all explain the contradictory orders and number of days (Genesis, 2.8). As for the discrepancy in sequencing, he teaches that “everything was created on the first” day but was “brought forth” on different days: for example, plants were created on the third day as the first version requires, but “they stood at the entrance of the ground until the sixth day,” after man was created (Genesis, 1.24, 2.5). Though this explanation takes the liberty to add midrashically to the text, it is at least plausible, but it nonetheless fails to account for the second version’s claim that creation was only one day long. As for how male and female were created, Rashi suggests, “He originally created [man] with two faces, and afterwards, He divided him” (Genesis, 1.27); other scholars expound: “In the first story of creation (Gen 1:27) an androgyne is made by Elohim. In the second account of creation, YHWH Elohim separates man and woman by creating Eve (Gen 2:18). Now the androgyne is split up into two distinctive creatures, a male and a female” (Luttikhuizen, 4). Dividing a hermaphrodite in half, however, is quite different from creating man and then extracting a single rib to form woman; thus, this interpretation neglects the clarity and specificity of the second account. In the creation story, “inconsistencies and contradictions…come down to us as a single work” (Brichto, viii)—so when someone identifies as a creationist, it begs the question: which version?

We have established the incoherency of the beginning of the creation story, and we have established that the main narrative contains serious enough discrepancies to undermine its integrity. None of these phenomena are introduced merely in translation; these contradictions, ambiguities, and grammatical peculiarities are rooted in the original text. The typical argument of “strict creationists” is a simple syllogism: “the Bible cannot be wrong”; “the Bible says the world was created in six days”; thus, “the world was created in six days” (Fitch, 3). The typical counterargument is to contest the former premise with science, but, as this argument has failed to convince 30% of Americans, this essay has taken a different approach by refuting the latter premise: that it is altogether uncertain how the biblical world was created, for the Bible first makes clear that it will not tell us when the beginning was—or perhaps implies that the beginning lasts forever—and then offers two contradictory answers for how long creation took. This is not a scientific argument, but a theological and literary one. If the biblical creation narrative is neither unified nor intelligible, how can it be read literally?

We have established the incoherency of the beginning of the creation story, and we have established that the main narrative contains serious enough discrepancies to undermine its integrity. None of these phenomena are introduced merely in translation; these contradictions, ambiguities, and grammatical peculiarities are rooted in the original text. The typical argument of “strict creationists” is a simple syllogism: “the Bible cannot be wrong”; “the Bible says the world was created in six days”; thus, “the world was created in six days” (Fitch, 3). The typical counterargument is to contest the former premise with science, but, as this argument has failed to convince 30% of Americans, this essay has taken a different approach by refuting the latter premise: that it is altogether uncertain how the biblical world was created, for the Bible first makes clear that it will not tell us when the beginning was—or perhaps implies that the beginning lasts forever—and then offers two contradictory answers for how long creation took. This is not a scientific argument, but a theological and literary one. If the biblical creation narrative is neither unified nor intelligible, how can it be read literally?

Reading the Bible as literature—concentrating on its language—tells us that Genesis 1-2 does not contain a literal account of creation, but this need not lessen its religious value, nor does it signify that the story has nothing to teach us. No one can explain what the first sentence of Genesis means, or even identify where it ends, but this allows for spiritual interpretations that transcend the literal; no one can reconcile the two creation narratives, but this duality encourages readers to grapple with the issues they raise concerning power dynamics, gender hierarchies, and human relations with the natural world. The “problems” in the Bible need not be problems at all: by unsettling any static interpretation, they prolong debates indefinitely and maintain engagement with important ethical dilemmas, encouraging us to question who we are as human beings and how we got here—but they do suggest that creationism is the one wrong way to read the Bible, for it halts the debates at the heart of religion. Where do we want our story to begin? What do we wish it to entail, in what order, with what end? The choice, says the Bible, is up to us.

Written in the style of Cicero (particularly his style of speeches like “Pro Caelio”)

Work Cited

Brichto, Herbert Chanan. “The Names of God: Poetic Readings in Biblical Beginnings.” (1998): i-481. ProQuest. Web. Dec. 2016.

Fitch, Walter M. “The Three Failures of Creationism: Logic, Rhetoric, and Science.” (2012): 1-194. ProQuest. Web. Dec. 2016.

“Genesis – Parshah Bereishit (show Rashi).” Chabad.org. Chabad Lubavitch Media Center, n.d. Web. Dec. 2016.

Giere, S. D. “A New Glimpse of Day One: Intertextuality, History of Interpretation, and Genesis 1.1-5.” (2009): 1-377. ProQuest. Web. Dec. 2016.

Goldwasser, Jeff. “Bereshit: In the Beginning of What?” Reb Jeff. N.p., 18 Oct. 2011. Web. Dec. 2016.

Goodhart, Sandor, and Monica Osborne. “Introduction: Reading Darkness: The Key, The Letter, and The Beginning.” MFS Modern Fiction Studies 54.1 (2008): 1-19. ProQuest. Web. Dec. 2016.

“In U.S., 3 in 10 Say They Take the Bible Literally.” Gallup.com. Gallup Inc., 08 July 2011. Web. Dec. 2016.

Luttikhuizen, Gerard P. “Creation of Man and Woman: Interpretations of the Biblical Narratives in Jewish and Christian Traditions.” (2000): 1-228. ProQuest. Web. Dec. 2016.

van Kooten, George H. “Creation of Heaven and Earth: Re-interpretations of Genesis 1 in the Context of Judaism, Ancient Philosophy, Christianity, and Modern Physics.” (2004): 1-299. ProQuest. Web. Dec. 2016.