Methologies III: Interpreting Performance

Posted in Assignments on October 5th, 2015 by Arielle Steele

Interpreting Performance

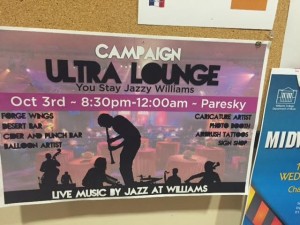

Last night, urged by the promise of an academic grade and a chance to practice real-time ethnographic research, I attended the Williams’ Campaign Ultra Lounge event. Held in the hub of student life, there in Paresky Center a mixture of students, professors, alumni and their children gathered for free food, gifts, and a host of other side attractions with the main one being the Williams College Jazz Band… or at least that was my perception.

I arrived at the event around 7:40 PM, wanting to get a chance to set up, take in my surroundings, and to eat since the event was slated to start at 8:30. I walked into Paresky Center entering Baxter Hall expecting the dimmed lights, hors-d’oeuvres, and décor suitable for an evening event, as the poster advertised.

Instead I walked into a perfunctory mish-mash of haphazard signs, some misspelled, luxurious appetizer tables, scantily decorated standing tables, and a solitary stage dotted with instruments and three purple columns too add some sense of flair (that admittedly it didn’t do much) to the setup. As the outdoor activities drew to a close, numerous bodies poured inside the center searching for warmth. The confused and excited crowd seemed more concerned with the heady spread of fall themed ‘deserts’ than the impending performance.

Anxious to begin our observation and participate in the night’s festivities that included a photo booth and caricature drawings, my classmates and I decided to staunch the pain of the wait with apple crumble in a cup, hot cider, chicken wings, and random note taking. This bought us maybe 15 minutes until we noticed it was 8:36 and not a movement was made toward the stage. The lights were on at full power and errant conversations about celebrities and people exchanging pleasantries surrounded me. Hurried students tried to hunt down the source of the ‘free gift’ (a portable phone charger adorned with the Campaign motto: “Teach It Forward”) a lucky 250 people would get for attending the event. The occasional parent-child duo milled around unsure of the ‘next big surprise’ the Campaign had in store for them.

Everything about this atmosphere read as if people could care less about the band and it’s apparent tardiness except for my classmates and I. So what did we do? Took more notes. The ferocity of our note taking interested many the passer by. “What are you guys writing? Is that, like, homework?” “What’s this little writing circle you guys have going on?” And the plain, almost aggressive “What is that?” were the questions our peers and alumni had for us. At first I responded saying that this “was a part of our Africana studies senior seminar class, and [that] we’re currently studying performance ethnography. We’re supposed to be taking notes on the jazz performance.” And with that people either joked about their apparent absence or left us alone, satisfied with the answer; but as the night wore on I got lazier and lazier and wound up saying, “Yeah this is homework for class” with a what-can-you-do face. In hindsight stationing ourselves in the back of the hall at standing table in the center wasn’t the brightest idea. We made a quasi-spectacle of ourselves in the absence of the band.

After these visits we realized this on some level and stopped taking notes. Partially tired of writing and tired of waiting, we took a break. My two classmates and I turned to the childhood game of *M*A*S*H*, to pass the time. It would be an understatement to say that this wait hardly put us in the mood to watch a performance. Even the crowd grew weary of waiting and petered out to a mere 70 some odd people still floating around. Fast-forward a whopping 30 minutes later, members of the band saunter onto stage and eek out a couple notes. I shook my head in disbelief at my cellphone screen that read 9:50 PM. The band seemed just as tired as I felt. Their movements oozed nonchalance as they slowly tested out the sound of their instruments. A blare of a horn here, a lazy sax note there, and timid keying of a piano made up the first sounds of the Williams Jazz Ensemble. Eventually they found it in themselves to play “Play That Funky Music”.

Being the first number of the show, the performance was still getting its legs. The musicians peered over at each other trying to match nonverbal cues with the rise and falls of the song. After a time the band seemed to ‘gel’ with one another. The base and the drums created an infallible foundation on which the horns, the saxophone, and the piano keys not only stood but also weaved in and out of one another. The band seemed to actually like what they were playing. For a moment it didn’t seem obvious to the meager audience that they were contractually obligated to be here.

However the true magic happened when another student provided vocals to the instrumental. At first it was unclear as to if he was a part of the ensemble. He sat down on the edge of the stage for about 20 minutes of the performance, and all the sudden he started vocalizing. Low and timid at first the voice seemed lost in the muddle of music, but as the song progressed so did the voice. With a bowed head and singular concentration the vocalist made his words stronger, clearer, filled with intent. It seemed as though the others felt this intention; the saxophone player especially. He not only swayed fervently to the singer’s words but he replied to them. The rest of the band lived within the pocket of music the two created. Though the crowd had dwindled to nil, the band played their best number. Two spectators even got up to dance to the smooth sound. In that juicy moment what happened could be described by Dwight Conquergood’s principal of dialogical performance:

This performative stance struggles to bring together different voices, world

views, value systems, and beliefs so that hey can have a conversation with

one another. The aim of dialogical performance is to bring the self and the

other so that they can question, debate, and challenge one another (Conquergood, 9).

The musicians heard each other’s ideas and expounded on them, responded. The people in the crowd saw this exchange of ideas and internalized them into their bodies. Though these ideas I am speaking of are purely abstract it doesn’t change the act of dialogue. Live music and dance is always a conversation, whether it is one-sided is up to the performers themselves. In this moment such an exchange was present. In this moment this was a good performance. However that crumbled quickly.

After becoming hyper aware of the fact they were playing to a mostly empty room, the musicians let the atmosphere die. They let this dialogue “dissolve [back] into the performer”, killing the beauty they had just created. They once again sounded as if they were in someone’s garage practicing for the hell of it, but not in a good way. The band seemed detached from the room, enveloped in themselves no longer reaching out for some sort of interaction with their intimate audience.

All this is to say that this was a lukewarm performance with little shining moments. Aside from two numbers, the jazz band seemed uninterested in their material and the space. The novelty of a heartfelt vocalist gave the performance the wings it needed, but just as quickly they came they left. The Williams Jazz Ensemble lacked connection, which made this event a venture I kind of regretted attending.