Research Project Proposal

Posted in Assignments on November 4th, 2015 by Arielle Steele

Arielle Steele

Prof. Manigault-Bryant

AFR 406

Project Proposal

The Black Literacy Project

Research Question

How do our environments inform what young black women, at Williams College, read and how they perceive blackness in the Young Adult literary canon?

Background and Significance

Being an English major with a passionate (and at times questionable) love of young adult (YA) novels, I decided to center my final project on teen readership, specifically black female readership. Aside from the obvious issues of lack of black representation in the genre, I had questions about how black teens are reading these texts, and what they’re reading.

When I reflect on my teenage years, most of the stories I remembered reading and loving were supernatural, sci-fi, and were very white. This wasn’t to say that I didn’t read any Morrison and the like, but my heart lead me to the young adult book store without fail. However as I read deeper into the genre, I noticed that in the young adult section most of the novels that were authored by black writers were stories of tragedy. These tragedies were not those of Nicholas Sparks-esque teenage folly. They were neither romance gone awry nor adventure epics with the world hanging in the balance. These were grim narratives determined and informed by, in my perception, the main character’s race. It was a reality that my teenaged self was unwillingly to face.

The young adult black literary cannon, past and present, has an oversaturation of stories centered on gang violence, dismal ghetto life, historical fictions that span anywhere from slavery to the Civil Rights Movement, or some tragedy stationed in an ambiguous Africa. Though there are excellent exceptions to the rule, such as Sharon Draper’s body of work, I found the limited scope for black teens disappointing. I recognized that these stories being told were necessary to our literary canon, as they are a part of the black experience, but I hungered for narratives of that existed outside the continuum of suffering. I wanted novels about black teens being black teens. In my time as a young adult, I maybe came across two books that had main characters of color doing “normal” teen things or were in fantasy worlds. So, with no solution in sight I continued to read fantastical novels.

But when I look back I wonder to myself was that really it? Was it because I couldn’t find black fantasy or was it because my environment was predominately white? I wanted to be able to relate with my friends in school and read what they read, and they weren’t reading Octavia Butler, Junot Diaz, Sharon Draper, Walter Dean Myers, or even Sister Souljah. My mom was the one who introduced The Coldest Winter Ever, the novel that spawned street literature, as we know it and rocked almost every black girl’s world but mine, to me. My church friends and Del-Teens group[1] (read: my black girl friends) loved the novel, yet I couldn’t even finish it. I hated it and I felt defective for it. I wondered why I could relate or at least sympathize with characters who time traveled, started revolutions, or saw ghosts, but couldn’t find it in myself to even like the main character Winter Santiaga. So this served as a driving force for my project. “How does predominately white environments (in academia) effect black female readership?”

Together with Professor Manigault-Bryant, I formulated the idea of a book club that would be primarily comprised of underclassmen at Williams to read The Coldest Winter Ever and The Hunger Games to see how black women are reading blackness and alternatively whiteness in these novels.

This work is ultimately important to the field of Africana studies because young adult literature is a site of latent race and gender theory that, for the betterment or detriment of the genre, is highly accessible. Books, falling into two categories which I affectionately call mirrors of life experience or windows out to alternate realities, carry our imbedded racial, sexual, gender, and class politics no matter the genre. Under the guise of entertainment, inclusive spaces, and literary worlds that allow for a reimagined self, these books, often unconscientiously, and sometimes insidiously, color young adults’ worldview with the biases of the author and publishers. Uncovering and deconstructing the ways these biases are interjected into YA novels in a way that is considerate to teens, and not academically alienating, we can sooner dismantle the literary politic of hegemony. The power to name, to define with the pen can be wielded in a healthier manner, by first understanding how these novels are actually being received amongst teens. We need to go beyond mere ‘representation’ and make the young adult novel radical again for marginalized people, not just another site of oppression. Ultimately the Africana Studies field is about analyzing the nexus of history, academics, and the political and the personal for African diasporic peoples; what can possibly be more personal the imagined world we create for ourselves when we read novels? The YA novel is a significant fixture of childhood that should be analyzed as a text of theory, because after all theory is an abstracted ideal, a guide to understanding the world around us that is constantly disrupted by our realities. [2]

Research Site

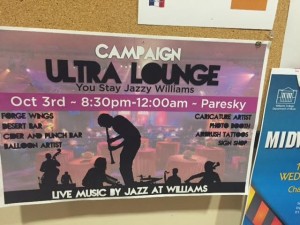

Bound by my inability to operate a vehicle and the subjectivity of my research, my work will be conducted on Williams College campus. To be specific, the observational period will take place over the course of four weeks, November 1-23, for an hour each week in Paresky 112; a space perfect for small gatherings. Simultaneously the other field of study will occur in online spaces.

Provided that my analysis cannot solely persist on the testimonials and dialogues of five young women, I will look to various blogs, articles, books, and interviews detailing the challenge of diversity in young adult literature. This issue is not novel by any means, but as the young adult genre becomes increasingly visualized via televisions shows and cinematic films, the culture and nature of discourse is in a state of constant flux. In order to provide the most accurate picture of black female readership at Williams and the racial/sexual/gender/class/ climate of young adult novels, authors, and publishers, a current snapshot of the field is necessary.

Theoretical Interlocutors

“For them, as for me, imagining is not merely looking or looking at; nor is it taking oneself intact into the other. It is, for the purposes of the work, becoming” (Toni Morrison, Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination).

At the heart of this study is the understanding that young adult literature constitutes more than the space of imagination, it is the philosophical creation of relationality, to the self and others. For Morrison and myself, literature encompasses the politic of being. Moving beyond the notion of the bildungsroman, a genre which arguably both texts (The Coldest Winter Ever by Sister Souljah and The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins) embody, the basis of young adult literature, all of which are imbued with the politics of identity, is about the formation and deformation of self-epistemology. Pairing this notion with the construal of blackness in literature, these books have the potential to serve as either a hegemonic or existential road map of black life.

Toni Morrison’s Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination not only observes this analysis but also details the formation of the American novelistic tradition through the lens of the formation of the black “other”, a notion that speaks directly to my questions of the real ramifications of blackness in the literary imaginary. Morrison deconstructs the ‘Great American Novel’ and its many incarnations (romanticism, the gothic, et.) for the use of black bodies as an amorphous repository for any ‘un-American’/anti-Puritanical sensibility. This could range anywhere from blackness representing an unwholesome desire to the creation of the ‘mad double’ in the gothic literary tradition. Ultimately this simultaneous disavowal of blackness and the black reader intrigues Morrison:

For reasons that should not need explanation here, until very recently, and regardless of the race of the author, the readers of virtually all of American fiction

have been positioned as white. I am interested to know what that assumption has meant to the literary imagination. When does racial “unconsciousness” or awareness of race enrich interpretive language, and when does it impoverish it?[….]In other words how is “literary whiteness” and “literary blackness made, and what is the result of that construction? (Toni Morrison, xii).[3]

Once again Morrison’s analysis has come to the crux of my research: what is blackness (to young black women)? It is the underlying question one must answer in order to construe how they are reading blackness in any given text.

Along side The Coldest Winter Ever and The Hunger Games, I will be using Morrison’s Playing in the Dark as a lens through which to form my scholarship, that ultimately is a question of existence. As Morrison says, “I was interested, as I had been for a long time, in the way black people ignite critical moments of discovery or change or emphasis in literature not written by them” (Morrison, viii). I want to know what lies beneath the slim scope of YA literature for young black women.

Methodology

Because my research question is one that requires an in-depth response that cannot be achieved through a cursory survey, and given the brevity of the project, I elected to employ ethnographical research in the form of a focus group, specifically a book club. This format will allow me to interview my participants in a lower stakes atmosphere, an atmosphere that is welcoming, informal, and void of the austerity that tends to plague the process. Furthermore because this ethnographical research is crafted in the book club format, the interviews will be more of a dialogue, in which I will be posited as a participant-observer.

Armed with discussion questions pulled from other book clubs[4] to ensure a neutral starting ground, I will slightly guide the conversation eventually allowing the participants to steer the conversation as the session wares on. Each meeting will take place weekly for the duration of an hour for four weeks. Given this time allotment, the roster for the book club must remain small to ensure thorough research.

Having these stipulations in mind, I casted my first call for participants in an email to a group of 16 black female underclassmen in the Williams College. I gathered their names using the networking of Facebook, choosing black underclasswomen. The selected participants were comprised of black underclasswomen under the premise of their youth and assumed availability (seeing as your academic career intensifies with each coming year). In addition to their academic status, this initial focus group was ideal because of their maintained proximity to the texts/subject matter, being teenaged black girls. However once I received only one response regarding the club, I had to rethink my study.

I then opened the study up to women I knew in the Williams College community to give new life to my study. While still small with a focus on teen readership, I now focused my attention on the thoughts and analyses of those present within my group. Ranging from ages 18 to 22, the four participants shaped my research in way in which incorporated a timeline into my research. Engaging in both books that are foreign to the subjects and familiar, the current participants offer a multilayered dialogue that converses with the past teenage self, as well as their present. This group has the potential to craft analyses that is the mediation between adolescence and adulthood.

Satisfied with the revival of my project, I held our first session on November 1, 2015. After getting settled in and agreeing to being recorded through audio means via verbal acknowledgement, the group got to work immediately discussing The Coldest Winter Ever. The method of recording proved to be unobtrusive to the discussion process, as participants spoke freely and honestly. So as the club progresses, Apple Voice Memo application will be the primary method of recording research. Overall I hope to collect my research through interpersonal means, relying heavily on verbal analyses primarily as we read the two texts, and in my supplementary findings utilize the analyses of literary critics, authors, and bloggers.

Findings

As I formulated this project I thought of all the ways the composition of my ethnography could be seen as invalid in its failure to provide objectivity and significant breadth. The fact that the subject of my research is centered on black teenagers and the cult of young adult literary canon, yet of my participants there are only two women who may be considered teens unnerved me. I pondered to myself, “Can my findings yield a proper analysis of the teen literary climate with subjects four years removed from the target age group?” “Does their respective removal provide an inaccurate picture of the teenage literary canon and its affects?” “Is this focus group actually indicative of the young adult black female readership?” These critical questions, qualms rather, plagued my mind as I began my research. Questions that could color my research differently, and ultimately tested the legitimacy of my work. I had to keep in mind that though my focus group is not ideal for the intended age-sensitive group study, their age does not necessarily render the rest of my participants’ contribution to my research invalid.

The beauty of my research lies in its subjectivity. My research asks about the personal experience with various texts, past, present, and possibly future. The advantage of having two teenagers and three young adult women is the range of perspectives, the knowledge of YA texts spanning almost 10 years. The interpolation of differing epistemologies will ultimately prove to be not only an unexpected addition to my research but a significant source of analysis.

This hypothesis eventually proved itself to be true from the very first book club meeting. Initially I expected the questions and themes of desiring a mirror vs. window out in literature/reality vs. fantasy, urban vs. suburban environments, and school vs. home in relation to literature to crop up as the ruling subjects of discussion in the book club, but our discussion evolved into much more. These dichotomies were a mere springboard for deeper conversation at our first meeting. After a brief series of introductions for both the members and the novel itself, the members instantly took the dichotomy of mirror/window-out into a conversation of representation. The depth of the conversation did not lie in the topic of representation itself, but in the nuances the members teased out of the ideology of representation. Outside of needing more authors and stories of color, the members asked if we could find value in the representations available to us. Providing that the cult of literature of color does not essentialize the Black/Latino/Asian/Indigenous experience, the women questioned if we reify the very same matrices of oppression on a given representation that allowed for such a small canon of literature to be published. That is if these stereotypical representations do in fact ring true for some of the black experience, is it entirely fair to chastise authors like Sister Souljah for portraying such a gritty narrative in The Coldest Winter Ever?

They then continued to postulate Souljah’s hard-nosed and often egotistical character’s place in the embodiment of female blackness. Winter’s determination to retain her “princess” status even when she had nothing, was worthy of note to the group.[5] Looking beyond the character’s belligerent attitude, the show of unabashed confidence was novel for a black girl character. So many narratives centering on black women deal with a coming of age or coming into the self, because the world we live in posit black women at the bottom of the racial hierarchy. Winter’s unwillingness to compromise is empowering through this lens.

Ultimately the subjectivity of their blackness and womanhood have allowed the members of the book club drive my research in both the right direction and unexpected avenues. Their dialogue has not only revisited and reconfigured notions of the place of the black YA novel, but also forced me to question the figure of the black woman in this world and the next. If our discussions continue on in this fashion, I expect that the results of this project will not only redefine the relationship between blackness and literature but also redefine black girlhood and womanhood for myself.

Bibliography (as of now)

Collins, Suzanne. The Hunger Games. London: Scholastic, 2010.

Kuficha, R. Dafina. “Emery Book Club.” Emerybookclub. March 7, 2011. Accessed November 1, 2015.< https://emerybookclub.wordpress.com/tag/the-coldest-winter-ever/>.

Kwaymullina, Ambelin. “Whitewashing: The Disappearance of Race and Ethnicity from YA Covers”. June 23, 2013. Accessed November 2, 2015. < https://insideadog.com.au/blog/whitewashing-disappearance-race-and-ethnicity-ya-covers>

Morrison, Toni. Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1992.

Souljah, Sister. The Coldest Winter Ever: A Novel. New York, New York: Pocket Books, 1999.

Steele, Arielle. BCBG Meeting One. Williamstown, Mass: Voice Memo Recording. November 1, 2015.

[1] Delta Sigma Theta Sorority’s Albany chapter had a female youth group I was a part of until my senior year in high school. The organization focused on the academic and social empowerment of black girls.

[2] Manigault-Bryant, Rhon. Class Notes on Africana Critical Theory. October 21, 2015.

[3] Morrison. Toni. Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination. 1992. Print.

[4] I will be using questions from the Emery Book Club’s WordPress site, for the duration of the first novel, The Coldest Winter Ever by Sister Souljah. <https://emerybookclub.wordpress.com/tag/the-coldest-winter-ever/>

[5] Steele, Arielle. (2015). BCBG Meeting One. [Voice Memo recording]. Williamstown, MA.

Word Count: 2733