The Federalist No. 68

The recent presidential election, in which the winner of the popular vote did not also win a majority of potential votes in the Electoral College, has revived interest in no. 68 of the Federalist papers published in 1787–88 by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay in favor of the proposed federal Constitution.

The recent presidential election, in which the winner of the popular vote did not also win a majority of potential votes in the Electoral College, has revived interest in no. 68 of the Federalist papers published in 1787–88 by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay in favor of the proposed federal Constitution.

No. 68, written by Hamilton, addresses the means of electing the President. He argues that electors, chosen for the special purpose, would be “most likely to possess the information and discernment requisite to such complicated investigations”. Such men (at the time, it was only men) would be “most capable of analyzing the qualities adapted to the station, and acting under circumstances favorable to deliberation, and to a judicious combination of all the reasons and inducements which were proper to govern their choice”. This would also “afford as little opportunity as possible to tumult and disorder”, which is to say, it would avoid mob rule. Nevertheless, the electors would represent “the sense of the people” who, in effect, delegate to a smaller body their right to elect a leader.

The question of how to elect the President and Vice-President caused great difficulty to the framers of the Constitution. They did not want the Executive chosen by Congress, which could lead to undue influence on the President by lawmakers; and they did not want the executive officers chosen by state legislatures, in whom the framers lacked confidence. Election directly by the people was rejected, as it would give the most populous states an unfair advantage over the least populous; and at any rate “the people” were thought unable to judge candidates well who were not known locally, given the breadth of the country. The framers expected that the candidate with the most electoral votes would be declared President, and the runner-up would be Vice-President, but if the votes were dispersed by state (as seemed likely) the final choice would fall to the House of Representatives.

In the event, the creation of political parties soon changed the nature of the electoral system. In the election of 1800, when Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr, from different parties, tied in the Electoral College, the election was decided by the House – on the thirty-sixth ballot. The Constitution was amended to prevent this from happening again, but the Electoral College has remained controversial, and calls to abolish it in favor of direct election by the people are heard today as they have been since before the Constitution was ratified. Most famously, the Anti-Federalist “Republicus” asked in 1788: “Is it then become necessary, that a free people should first resign their right of suffrage into other hands besides their own, and then, secondly, that they to whom they resign it should be compelled to choose men, whose persons, characters, manners, or principles they know nothing of? And, after all (excepting some such change as is not likely to happen twice in the same century) to intrust Congress with the final decision at last? Is it necessary, is it rational, that the sacred rights of mankind should thus dwindle down to Electors of electors, and those again electors of other electors?”

Once again we are reminded that history holds lessons for the present day, and the words of the founders of the United States, and of their critics, are still worth reading. Many books and documents from the time of the framing, ratification, and amendment of the Constitution are in the Chapin Library at Williams, including two copies of the first collected edition of The Federalist (1788). These and other important materials are available in the Special Collections reading room in Sawyer Library (Room 441) or on display in the Chapin Gallery (Sawyer 406). – WGH

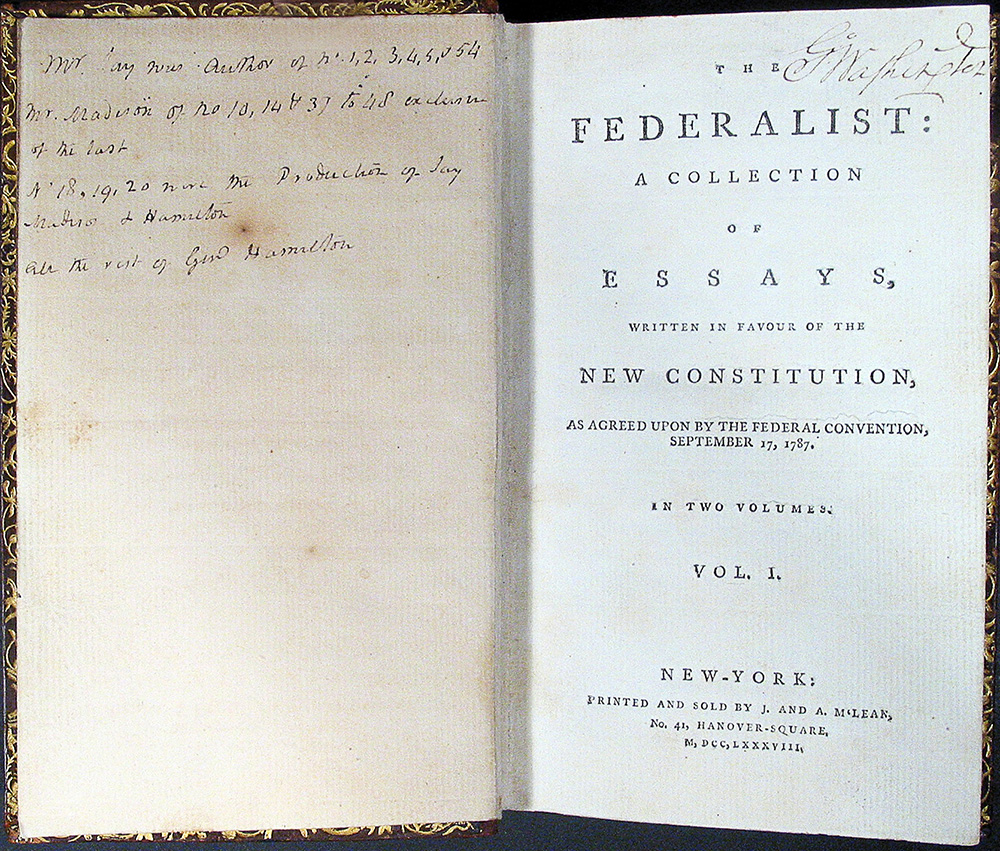

Shown is the title spread to volume 1 of George Washington’s copy of The Federalist, given him by Hamilton and Madison.