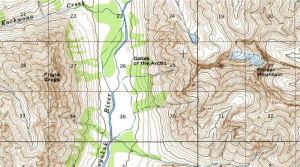

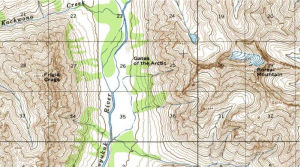

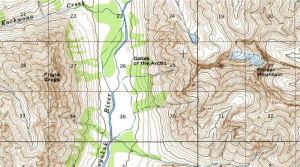

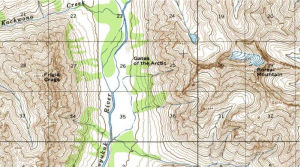

Ever since I spent a few days lost in the tundra of Northern Alaska, I have been in love with topographical maps. I think they are incredibly beautiful, and I am fascinated by the way they depict the world so scientifically without looking like the landscape they represent. Maps of the wild and of the geo-political world fascinate me, and apparently they have fascinated the world for all of human history.

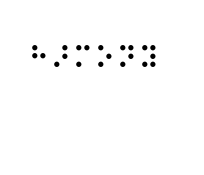

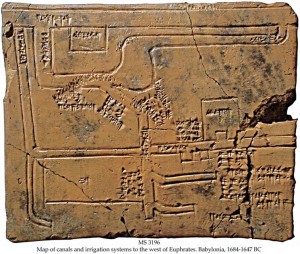

The human need to map the world we live in, to record and depict it, predates the written word (Clark 6). Fundamentally, mapping is about “the transfer of information from one form of presentation into a re-presentation of that information,” an effort that is both scientific and artistic (Pickles 75). Maps are not depictions of absolute fact; any two dimensional map is inherently inaccurate in terms of shape, distance, area, and/or direction, and cartographers’ choices on which information to sacrifice have effects beyond the page.

The technology of the 21st century has improved the accuracy and detail of maps; in fact, we are more and more using photographs (think Google maps) rather than drawing or graphs to navigate the world. However, the methods of old are still used today as well. Triangulation, or using trigonometry to establish distances between objects, is still used by surveyors, especially in mountainous areas. Sonar, GIS, and satellite images have also been added to the arsenal of tools.

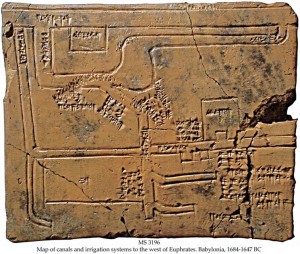

The oldest maps we know of (on clay blocks) were probably used to establish ownership of certain land areas (Clark 18). However, just as soon as we were mapping the earth, we began mapping the stars. Many surviving maps from centuries past were used by sailors, in conjunction with the stars, to follow trade routes. The undiscovered world was designated by images of sea serpents and other frightening creatures, with the inscription: “Here be dragons” (Casey 10). Other ancient maps were mostly artwork, adorned with elaborate pictures of gods and spirits, meant to depict the relationship between the realm of deities and the earth.

During the 2nd century, the Greco-Egyptian Ptolemy (famous for his geocentric model of the universe- another map) established the convention of putting the equator in the center, and invented the concept of a prime meridian as well as longitudinal and latitudinal lines (Clark 38). Centuries later, Columbus used Ptolemy’s maps in an attempt to reach Asia by sea; the Greco-Egyptians only knew of Africa, Asia, and Europe.

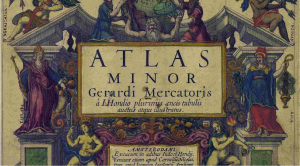

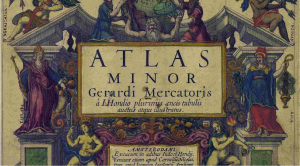

The 16th-17th centuries are considered the “Age of Atlases” (Clark 116). The 1500s saw a rise in the use of pictoral representations of mountains and rivers, although altitude was not accurately scaled. In 1590, cartographer Gerardus Mercator published a book of maps depicting the god Atlas holding the world on the front cover, and the term “atlas” was born (Clark 106). By 1686, maps included wind patterns, and sailors began adjusting for the difference between true north and magnetic north (Clark 52).

However, maps are not just reflections of observations, attempts at mirroring the natural landscape; throughout history, maps have also been used as the source of truth. 16th and 17th century land disputes between France and England over North America were fueled by propaganda maps that showed differing divisions of the land (Clark 120). The borders we see between countries and states are man-made designations that we have imposed on the world and put our faith in. The famous Peters projection depicts the earth south-side up, challenging a convention started by Europeans who (naturally) placed Europe above other countries (we are just floating in space, and the magnetism of the planet switches so it truly is arbitrary).

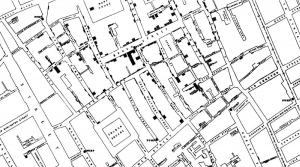

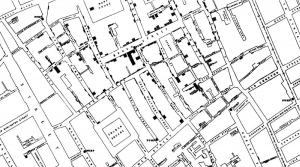

Other maps reveal truths. For example, scientist John Snow famously mapped the spread of cholera and used his findings to theorize the existence of germs (Clark 66). Maps that move through time can show the spread of a civilization or a religion.

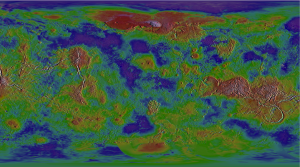

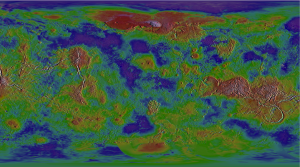

We also use maps to depict landscapes we will never see, reaching to the arms of the universe and to our inner beings. We send million-dollar probes to Venus and use sonar to penetrate the thick atmosphere and create a graph of the topology of its surface (Clark 100). We make maps of our own brains, trying to understand it as a space with divisions and specific functions. What Lord of the Rings or The Phantom Tollbooth fan hasn’t traced the paths of the characters through the maps on the inner book cover?

Our apparent obsession with mapping has bases in both pragmatism and the human desire for adventure. The maps of the tundra of northern Alaska, for example, were funded by the cold war military, showing details of topography and brush cover to use in the case of ground warfare. However, these lands were first scouted by the explorer Bob Marshall, who returned again and again to that land where the sun circles the sky in summer and never rises in winter for the sake of discovery. On the other end of the Earth, lives were lost in epic expeditions to the South Pole, in attempts to find the center and be the mapmakers. We are trying to map the ocean floor, perhaps for finding fossil fuels but also for the sake of discovery.

As we know more of the world, we reach farther away, searching for more of the unknown. We are looking at places we may never go, planets we may never see, and yet we try to understand the lines and edges, the curve of the land and the size of the oceans. The human race is on a never ending search for its dragons.

Works Cited

Casey, Edward S. Earth-mapping: Artists Reshaping Landscape. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1939. Print.

Clark, John O. E., ed. 100 Maps: The Science, Art and Politics of Cartography Throughout History. New York: Sterling Publishing, 2005. Print.

Pickles, John. A History of Spaces: Cartographic Reason, Mapping and the Geo-coded World. London: Routledge, 2004. Print.

Images

https://soloswimmer.wordpress.com/2012/07/17/here-be-dragons/http://www.thecanyon.com/http://www.americansouthwest.net/topo-maps/north-kaibab-trail2.jpghttp://expositions.nlr.ru/eng/map_merkator/4.phphttp://www.stonegallery.info/graphics/17thmapgraphics/ml-0693.jpghttp://blogs.plos.org/publichealth/files/2013/03/John-Snows-cholera-map-of-009.jpghttp://laps.noaa.gov/albers/sos/venus/venus_shaded.jpghttp://vignette3.wikia.nocookie.net/lotr/images/7/72/Middleearthmap.jpg/revision/latest?cb=20100402045252http://www.nps.gov/gaar/planyourvisit/images/The-Gates-map-800×500.jpg