Objects were central to religious worship in late medieval Christian Europe. From the chalice used to celebrate the ritual of the Eucharist to the rosaries and books of hours that assisted the faithful in their devotions, material things helped to regulate and make tangible the sacred. In the Reformations, objects gained a new salience when many Reformed believers came to see them as the graven images condemned in the Old Testament–symbols of idolatry.

Inspired by recent scholarship, the students of History 330 (Spring 2020) have approached Reformation-era material culture to investigate the different histories of the sacred that objects tell. In spite of iconoclasm, many late medieval objects survived into modern times. Indeed, they did more than survive. As Caroline Bynum writes, “The materiality of objects carries forward the experience of people in the past.” Paying attention to that materiality can help us understand religious continuity and change in a more multifaceted and nuanced way than can the study of doctrines and decrees alone. ❧

A donor and his sons protected by his patron, a bishop

Flanders, c. 1520

Stained glass

Dimensions: 21 3/4 × 19 1/2 in. (55.2 × 49.5 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

This pane of stained glass, produced by an unknown Flemish artist ca. 1520, can best be described as a donor portrait: capturing the religious devotion of a wealthy churchgoer. The work was produced in Mechelen, in present-day Belgium, and had an accompanying sister-pane, which depicted St. John overseeing a number of praying women. The donor is depicted at front, cloaked in a luxurious, intricately patterned overcoat in conjunction with his two sons who, like their father, are kneeling in prayer. The standing figure appears to be a bishop, donned in his elaborate miter and equipped with his crosier. Perhaps the pane’s most striking visual feature is the tortuous detail present in the work’s foreground and background; the trees seen through the spaces between adorned columns have individual leaves, and the plush fabrics worn by the figures have depth and vibrancy. This painstaking detail and the presence of the bishop in the work likely reflect the wealth of the donor. Although visually striking, works such as this stirred controversy among early 16th century religious reformers, who believed that lavish material patronage to the Catholic Church—which this window represented—proved largely incongruent with scriptural teachings. The year of the work’s production, 1520, was a significant one for the Protestant Reformation: within the span of that calendar year, the movement’s most prominent German thinker, Martin Luther, produced some of his most famous works, including To The Christian Nobility of The German Nation, which directly addressed the notion of transactional Christianity. (Will K.)

Saint Michael

Touraine, France, c. 1475

Limestone w. traces of paint and gilding

Dimensions: 33 1/2 x 17 7/8 x 12 in. (85.1 x 45.4 x 30.5 cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Covered Chalice

Toledo, Castile-La Mancha, Spain – late 15th century

Silver, gilded with rubies, sapphires, diamonds, and crystals

Dimensions: 17 3/16 x 7 3/4 in. (43.7 x 19.7 cm)

The objects in this exhibition are meant to help us further our understanding of our course’s titular concept: Reformations. So why have I chosen a chalice from Spain, the heartland of the Catholics and a bastion against the threat of Protestant Reformation? Precisely for this history. The chalice is made of solid silver and precious gems, such as diamonds, rubies, and sapphires: quite a haul. Even subtracting out the added value from the workmanship and labor necessary to craft such an object, the chalice must have been worth a great deal in the raw materials it was made of. That it has survived to modernity without being smashed or melted down suggests its insulation not only from religious hatred but also pecuniary greed. Can this lead us to wonder whether the more open acceptance of Protestant values, and specifically iconoclasm, in German lands might have been primed by economic factors as much as theological reasoning? The chalice was also a symbol of the divide between the laity and the clergy, as only priests were allowed to drink the blood of Christ from the chalice in the ritual of the Eucharist. Were the Spanish less resentful of the hierarchy that elevated priests over commoners? Finally, the chalice’s primary purpose, embellished with busts of Christ and the Latin uttered by archangel Gabriel announcing the forthcoming birth of Christ, seems to be to worship the Son. Yet there are also representations of the saints that might be criticized as idolatrous deifications … but is the blasphemy so clear? (Giebien N.) ❧

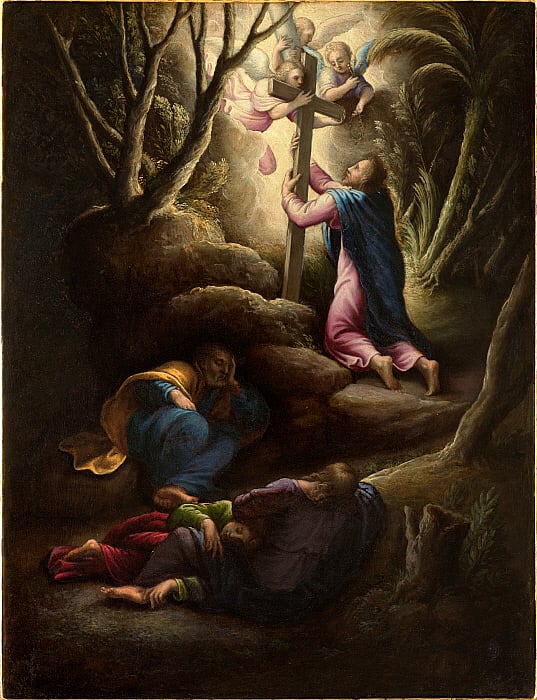

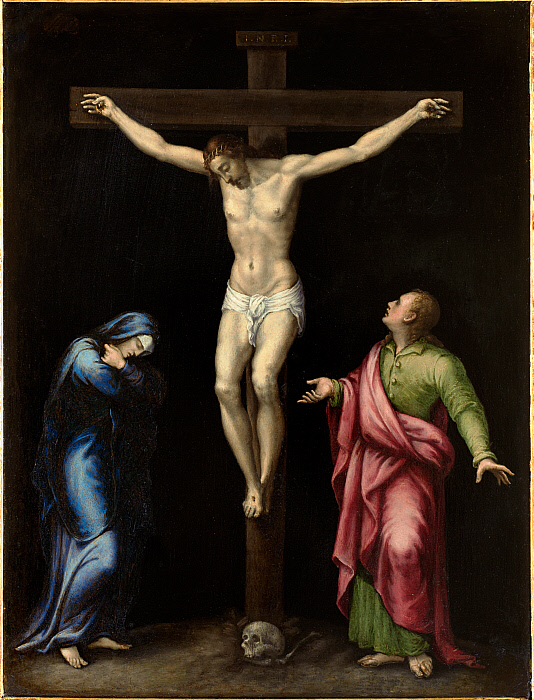

Giovanni Battista Cremonini, The Agony in the Garden (r); The Crucifixion (v)

Northern Italy, c. 1595

Oil on copper

Dimensions: 16 5/8 x 12 9/16 in. (42.2 x 32 cm)

Clark Institute

This work by Giovanni Battista Cremonini (ca. 1595) is an oil-on-copper depiction of the Agony in the Garden and the Crucifixion of Christ. Painted on both sides, it would not have been hung on a wall, but likely displayed so that both the Agony and the Crucifixion would be visible to the viewer. This feature distinguishes the panel from most painted art; it was more of a painted object and less of a painting, as it would have stood on a support rather than hanging on a wall in the periphery of a room, and thus have been more prominent. This method of display would also have invited the viewer to walk around it. Cremonini makes effective use of dramatic lighting in both scenes of the panel. In the Agony in the Garden, the only source of light is heaven, from which angelic figures seem to communicate with Christ. The face of Christ is illuminated, but the divine light does not travel far; His sleeping disciples do not share their master’s illumination, and much of the background is completely invisible to the viewer. This represents the absolute saving power of God. In the Crucifixion of Christ, there is no source of light whatsoever. The two onlookers, likely St. Mary and St. John, lack haloes, as does Christ. The total blackness of the background and the absence of divine light emphasize the devastation felt when Christ died, and the absence of a halo emphasizes His human aspect. (Brendan K.)

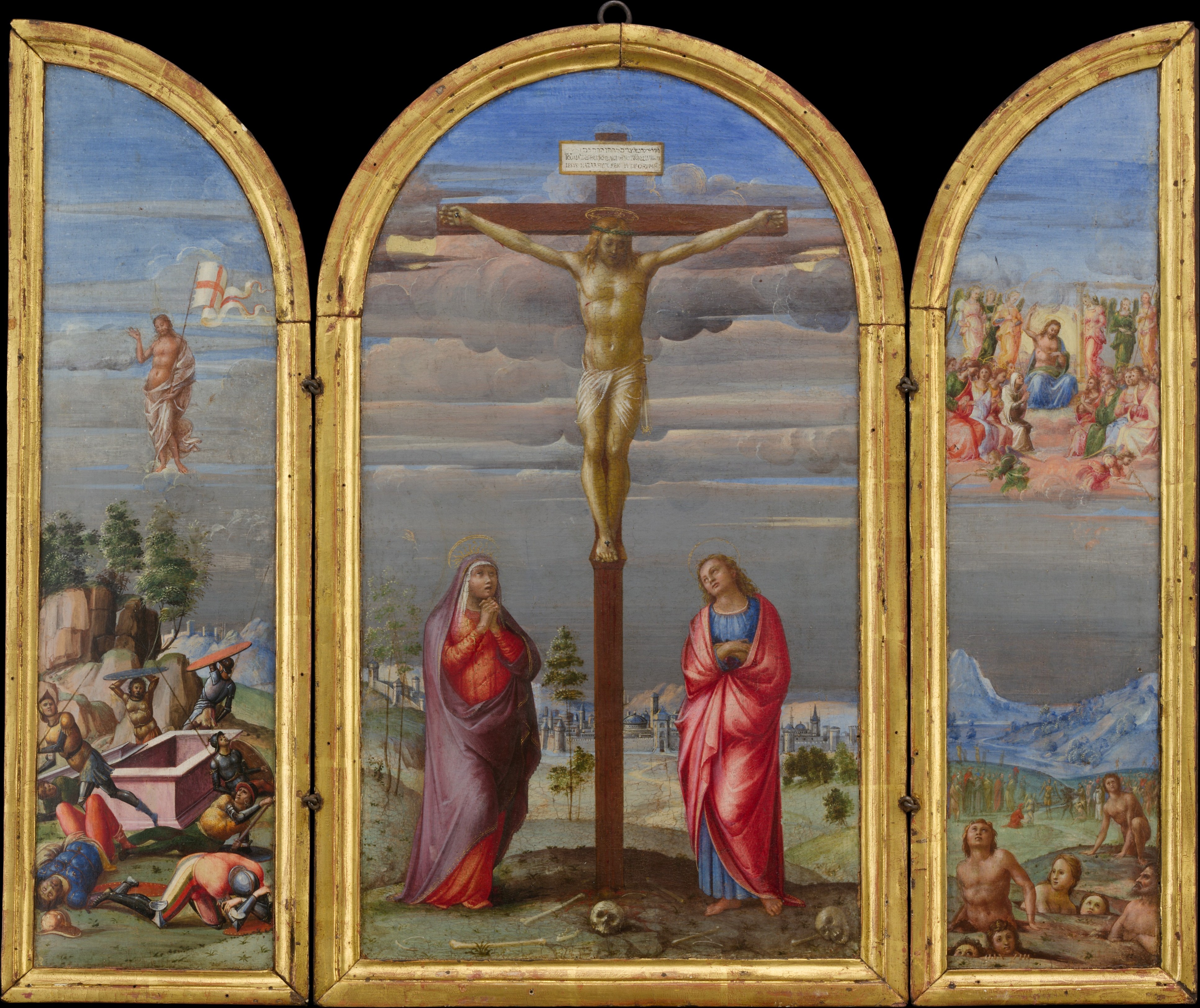

Francesco Granacci (Francesco di Andrea di Marco), The Crucifixion

Central Italy, ca. 1510

Medium: Tempera and gold on wood

Dimensions: Central panel 19 x 11 1/2 in. (48.3 x 29.2 cm); each wing 19 x 6 in. (48.3 x 15.2 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

As a piece meant for private devotion, this triptych exemplifies the trend among early modern Christians to worship in their own homes. Standing at less than two feet tall and a foot wide, the triptych could have been transported easily. Its size and elegant design suggest it may have been made for someone wealthy enough to commission such a piece but not wealthy enough to build their own private chapel, as was common among the elite in Florence at the time. Each panel represents a different scene from Christian teaching. The left panel displays the Resurrection, Jesus on the Cross in the middle, and the Second Coming of Christ on the right panel. This work also includes three separate translations of “Jesus Christ King of the Jews” on the cross in Latin, Greek, and Hebrew. The triptych’s painter, Francesco Granacci, was active in 16th-century Florence. He studied under Domenico Ghirlandaio with Michelangelo, whom Granacci would go on to assist in painting the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel for a short while. The two were close friends, and their styles were so similar that a painting originally attributed to Granacci was found to be one of Michelangelo’s works. Granacci would continue to paint Catholic images until his death in 1543. (John R.)

Otto van Veen, The Martyrdom of Saint Andrew

Netherlands, c. 1595

Oil (brunaille) on paper; framing line in pen and brown ink, probably by a later hand

Dimensions: 11 1/4 x 7 5/8 in. (28.6 x 19.3 cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Saint Andrew was crucified on a unique X because he considered himself unworthy of the cross that Jesus died on; it became his symbol. Here he is being prodded by soldiers and saved by angels as chaos ensues around him. The question of whether it was acceptable to worship images such as this one ignited an iconoclast movement during the Reformations, largely led by men of higher rank from the church or state. Despite their often-aggressive efforts, the worship of images and objects never truly went away. An example of this is Otto van Veen’s “The Martyrdom of Saint Andrew,” an oil sketch on paper completed in 1595. This preparatory sketch was made for the high altar of a church, Antwerp’s church of Saint Andrew. It was, in other words, part of an effort to restore traditional worship after the iconoclast movement in Flanders. It is notable that the Church of Saint Andrew in Antwerp had many portrayals of martyrs. They are a critical part of early Christianity. Perhaps the representation of martyrs served not only as a way to honor those who died for their beliefs but also to remember all the precious art that had been destroyed just a few years before. (Frankie S.) ❧

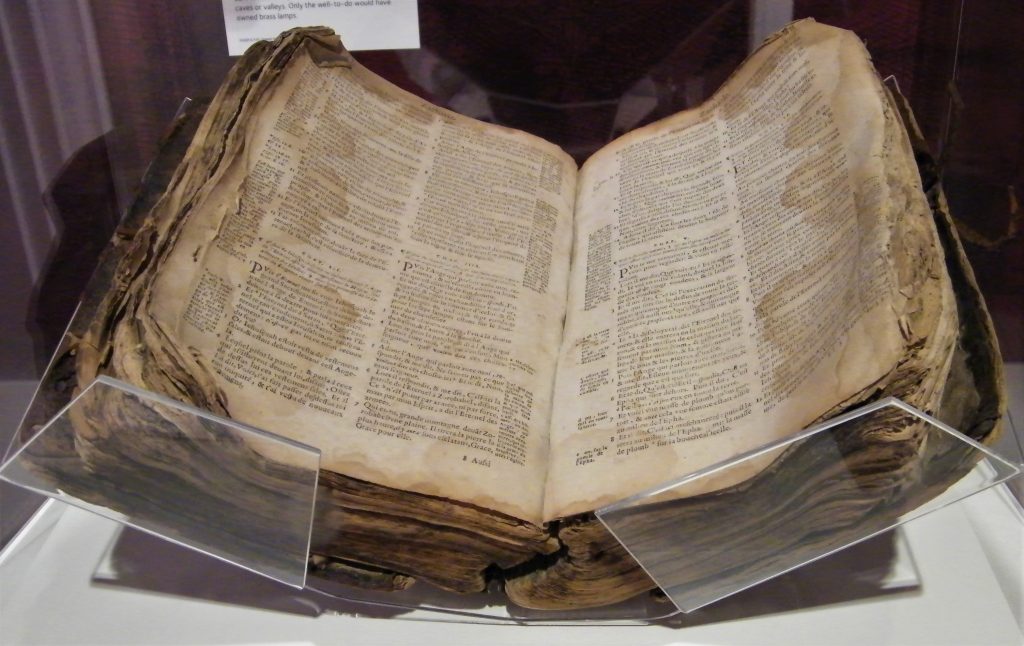

French edition of the Geneva Bible, c. 1590

Huguenot Museum

4. Female Piety in the Reformation Era

Alessandro Allori, Portrait of Joanna of Austria

Late 16th century

Oil on panel

Dimensions: 17 1/8 x 13 11/16 in. (43.5 x 34.8 cm)

Williams College Museum of Art

This portrait of Joanna of Austria was created in Florence during the 16th century by Alessandro Allori. Though this may not be one of Allori’s most memorable works, the subject of his creation — Joanna — was quite an interesting individual. The daughter of Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand I, Joanna grew up the youngest of fifteen and never met her mother, who unfortunately died during her birth. At just 18, the young woman was married off to a wealthy member of the Medici family, despite her protests, and was forced to move with him to Florence. Upon arriving, she was heavily discriminated against for her Austrian background, and also received criticism for not being able to produce a male heir for her husband. Finally, things began to be looking better for Joanna after she delivered a son (her 7th child), but young Isaac passed shortly after his birth. Just a year later — during her 8th pregnancy in 13 years — Joanna fell down the stairs and was forced into early labor, which eventually led to her demise at just 31 years old. This tragic life story of Joanna of Austria proves that although a few powerful women — such as Queen Elizabeth I — were able to overcome gender stereotypes and have a prominent role in the Reformation era, the majority of royal women were still seen as little more than child bearers and housekeepers by society, despite their elite status. (George C.) ❧

Jacques Callot, Les Martyrs du Japon (The Martyrs of Japan)

France, ca. 1627

Etching on laid paper with watermark

Dimensions: sheet: 17.1 x 11.7 cm (6 3/4 x 4 5/8 in.); platemark: 16.7 x 11.3 cm (6 9/16 x 4 7/16 in.)

Cleveland Museum of Art

The typical tale of Jacques Callot is a two-act affair. Act One profiles Callot the witty satirist, cataloguing his ascent to prominence under Medici patronage in Florence from 1609-21, when he excelled in producing lively caricatures of secular subjects – drunkards, hunchbacks, jesters, and the like. Act Two, spanning 1621 to his death in 1635, foregrounds Callot the stern moralizer. Against the backdrop of the Thirty Years War, Callot, having returned home to serve the court at Lorraine, produced his most famous set of prints, entitled “The Miseries and Misfortunes of War,” depicting war crimes carried out ostensibly under the banner of creed. This 1627 print, emerging from that context, undermines clean notions of rupture between the ‘two acts’ and ‘two Callots’ of his career. This is irony in earnest. The scene recalls news from Nagasaki, in February 1597, that twenty-six Christians had been crucified on orders from the Japanese Emperor Hideyoshi Toyotomi. The Japanese had in 1549 welcomed Jesuit missionaries under Fr. Francis Xavier, hoping to strengthen mercantile and cultural ties with Europe. As suspicions that Catholicism was a euphemism for colonialism festered, the relationship took a violent turn. Europeans were quick valorize the martyrs, casting palms and laurels from afar like the angels in the scene. But Callot’s wry wit – in a decidedly dark register – entreats viewers to consider whether their religious zeal to ‘emulate Christ,’ at home and abroad, could lead only to an endless line of misunderstandings – crucified victims receding endlessly, senselessly, into the background of history. (Robert D.) ❧