Up until now we’ve seen revolutions depicted as contingent, even arbitrary events, the overthrow of kings and autocrats little more than happenstance, the unexpected, even unintended consequence of a fateful encounter between stumbling authority and a member of the crowd brave or exhausted enough to finally, definitively, say “no.”

This week’s readings presented us with nearly the opposite scenario: Revolutions as performance (Furet and Arendt), as incurable pathology (Arendt), an irresistible novelty (again, Arendt, and to a certain extent, Tocqueville), or in the case of Camus’ rebel, as redemption of an irrepressible human spirit. These accounts were met on the one hand by the skepticism of Burke (revolutions are bad) and Tocqueville (revolutions are unlikely in an era of equality), and on the other by the absolute certainty of Marx and Engels that (class) justice will be served (revolutions as historical necessity, the consequence of teleology).

Very briefly, between the two conceptual poles presented thus far in the course—revolutions as accidental affairs versus revolutions as destiny—where do you stand, and why? Use this blog post as preparatory notes for next week’s discussion.

Below, I’ve listed a number of passages that may help you as you consider your answer:

“Civil wars have generally been assumed to be sterile, bringing only misery and disaster, while revolutions have often been seen as fertile ground for innovation and improvement…civil wars are local and time-bound, taking place within particular, usually national, communities, at particular moments. By contrast, revolution seems almost a contagion, occurring when it does across the world, at least the modern world, which in a sense it defines, as an unfolding progress of human liberation.” Armitage, Civil Wars: A History in Ideas, pg. 122

“We insist that the part of man which cannot be reduced to mere ideas should be taken into consideration—the passionate side of his nature that serves no other purpose than to be part of the act of living…Rebellion, though apparently negative, since it creates nothing, is profoundly positive in that it reveals the part of man which must always be defended.” Camus, The Rebel, pg. 19

“…a revolution is an attempt to shape actions to ideas, to fit the world into a theoretic frame. That is why rebellion kills men while revolutions destroys both men and principles.” Camus, The Rebel, pg. 106

“The modern concept of revolution, inextricably bound up with the notion that the course of history suddenly begins anew, that an entirely new story, a story never known or told before, is about to unfold, was unknown prior to the two great revolutions at the tend of the eighteenth century. Before they were engaged in what then turned out to be a revolution, none of the actors had the slightest premonition of what the plot of the new drama was going to be.” Arendt, On Revolution, pg. 21

“Only where this pathos of novelty is present and where novelty is connected with the idea of freedom are we entitled to speak of revolution. This means of course that revolutions are more than successful insurrections and that we are not justified in calling every coup d’état a revolution or even in detecting one in each civil war…All these phenomena have in common with revolution that they are brought about by violence…but violence is no more adequate to describe the phenomenon of revolution than change; only where change occurs in the sense of a new beginning, where violence is used to constitute an altogether different form of government, to bring about the formation of a new body politics, where the liberation from oppression aims at least at the constitution of freedom can we speak of revolution.” Arendt, On Revolution, pp. 27-28

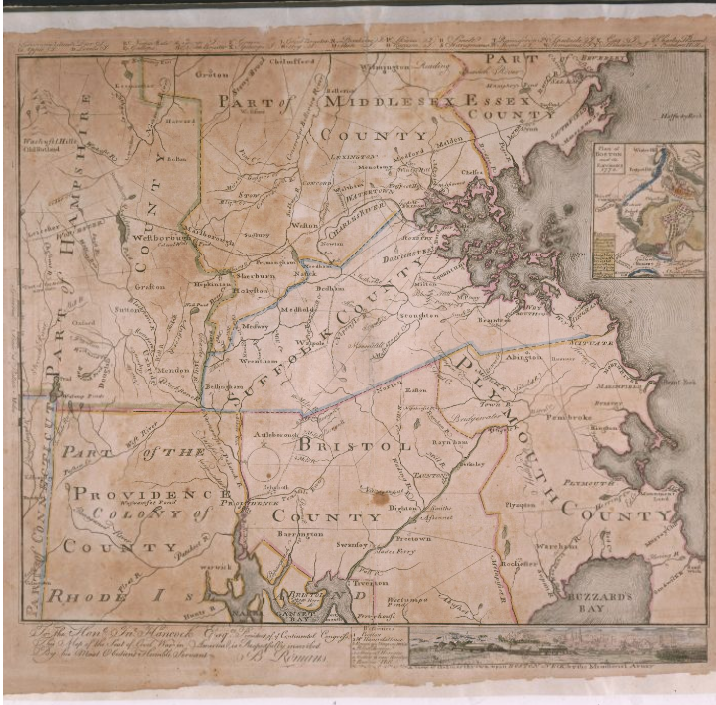

To the Hone. Jno. Hancock Esqre. President of the Continental Congress; This Map of the Seat of Civil War in America is Respectfully Inscribed

To the Hone. Jno. Hancock Esqre. President of the Continental Congress; This Map of the Seat of Civil War in America is Respectfully Inscribed