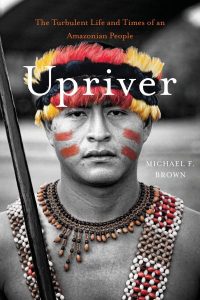

“Upriver: The Turbulent Life and Times of an Amazonian People” (2014)

Upriver: The Tu rbulent Life and Times of an Amazonian People, by Michael F. Brown. Harvard University Press. Hardcover, $29.95 • £22.95 • €27.00, ISBN 9780674368071, September 2014. Find a bookstore.

rbulent Life and Times of an Amazonian People, by Michael F. Brown. Harvard University Press. Hardcover, $29.95 • £22.95 • €27.00, ISBN 9780674368071, September 2014. Find a bookstore.

Books about unfamiliar social worlds take many forms. There are studies based on scientific description (“The Erewhonians live at latitude X, longitude Y, and their current population is 12,000”), romantic ones that emphasize exotic customs and beliefs, and analytical accounts that marshal evidence in the service of a larger point. In the Amazonian case, variations on the latter are as diverse as the ecology of the rainforest itself: materialist, symbolic, sociobiological, historical, feminist, psychoanalytic, linguistic, ontological, even psychedelic.

If forced to classify Upriver, I’d call it a portrait of a distinctive people’s everyday life, written in straightforward prose and attending to the complexity of lived experience. Stylistically, the book leans toward the laconic as a way to honor negative space, the things that remain unknown and perhaps unknowable to an outsider. (Sample passages from the book are viewable here.)

Upriver chronicles the modern history of the Awajún (Aguaruna) people of Peru’s northern montaña, a rugged zone where the Amazon and Andes meet. The Awajún must be counted among the continent’s toughest and most resourceful indigenous peoples. They are closely related to the better known Shuar (Jívaro), with whom they shared fame for their resolute resistance to European rule.

From p. 47: “A large-scale Awajun assault in 1914 led to the immediate abandonment of the Marruecos rubber station. ‘Uprising of Aguaruna Indians,’ clamors the headline of an account of the attack published in a Lima newspaper.”

During the Rubber Boom (1879-1912), Awajún war parties attacked Peruvian villages and raided indigenous rivals on a regular basis.

By the late 1940s, however, they had begun to gather in relatively stable villages and engage more peacefully with missionaries and settlers. They were among the first groups in the Peruvian Amazon to come into contact with American missionary-linguists, who promoted both evangelical Protestantism and literacy in Spanish and Awajún. Missionaries trained the first cadre of Awajún leaders who could communicate effectively across cultural boundaries.

I landed in their midst late in 1976 after abandoning a project elsewhere in eastern Peru. My acceptance by the elders of a village called Huascayacu—one of nine Awajún communities then established in the valley of the Alto Río Mayo, not far from the town of Moyobamba–represented a form of cultural exchange. I was given permission to study the villagers. They, in turn, were free to study me.

Impressed by the geniality and good humor of my hosts, I was soon troubled to learn of their intense fear of sorcery and their sometimes violent response to it. This had led to suspicions that were tearing the village apart. Equally unsettling was a high rate of suicide (among the highest reported anywhere in the world), especially among girls and young women. Buried even deeper under the surface of everyday life was a history of murderous vendettas in which most of the men had been involved years before.

Over the roughly twenty months that I lived in Huascayacu and a second village, a complicated picture emerged. In contrast to the stereotype of indigenous Amazonians as deeply committed to traditional spirituality, the Awajún I knew had mostly abandoned their ancient rituals, the sole exception being shamanic healing involving the use of the hallucinogen ayahuasca. Some converted to Christianity and even, in a few cases, to the Baha’i faith, although there was plenty of backsliding over time.

What they didn’t give up on was their identity as Awajún. They saw themselves as smarter and tougher than the colonists pouring into the region from played-out fields in the Andes. They were determined to acquire the education and political skills needed to defend their lands from outsiders. It is no accident that Awajún leaders were disproportionately represented in the indigenous federations that began to spring up throughout Peru and elsewhere in South America.

Upriver consists of two parts. The first focuses on events in 1977 and 1978. I visited the Alto Mayo almost annually afterwards until that pattern was broken by Peru’s Shining Path insurgency, which by the late 1980s made fieldwork unacceptably risky to me and to anyone receiving me hospitably.

The second part describes the Awajún’s trajectory through 2012, when I visited the scene of my earlier work and interviewed university-educated Awajún in Lima, one of whom, Eduardo Nayap, had become the first indigenous Amazonian elected to the Peruvian Congress.

Some of my 2012 discoveries were surprising. Traditional Awajún dress and adornment, scarcely to be seen in the Alto Mayo in the 1970s, had been revived, although mostly for strategic assertions of ethnic identity. Awajún intellectuals talked about reviving the traditional vision quest, but in a new form focused on educational and economic advancement rather than success in combat. The Awajún population had doubled to nearly 55,000 since the early 1970s, and legally titled Awajún lands together comprised territory nearly as extensive as the state of New Jersey.

Yet the pressure on these lands had increased as well—from the Awajún’s growing population and, more important still, from the extractive policies that propel Peru’s booming economy. The only thing that restrains complete despoliation of Awajún country by petroleum and mining interests is Awajún militancy, which manifested itself spectacularly in the violent 2009 encounter popularly known as the Baguazo.

From p. 230: “The official record states that the multiple clashes of the Baguazo resulted in a total of 33 confirmed deaths, one police officer missing and presumed dead, and 200 injured . . . Most unnerving to the Peruvian public was that more than two-thirds of the reported dead were policemen, including members of an elite special operations unit.”

Where the the fate of the Amazon rainforest and its Native peoples are concerned, most 21st-century accounts end on a gloomy note. Yes, there is much to be concerned about, much injustice to be rectified and cultural loss to be mourned. But despite these challenges, the Awajún are determined to carry on. Their ambition and self-confidence, honed by their ancestors in the field of war, is now directed to education, economic activities, and the struggle for self-determination. Perhaps the greatest irony of their experience is that the traits that powerfully marked them as “uncivilized” in the minds of Westerners—combativeness, suspicion of the motives of others, impatience with social hierarchy and assertions of control by outsiders—are the qualities that have allowed them to survive in what passes for civilization on the Amazonian frontier.