The Elephant Story

Dali, Salvador. “The Temptation of Saint Anthony.” DaliPaintings.com

The Elephant Story

ZsaZsa Morel

Ekphrastic Approaches: Main Figure Ventriloquism, Description, Minor Figure Ventriloquism, Interrogation of self, Giving an Account of my Experience

A wild white horse and five elephants, all with tall spidery legs, are marching towards me. They call out my name and attempt to tempt me…

Saint Anthony leans against a rock while holding up a cross to cast out the demonic figures who were sent to tempt him. They march in a line towards him. A large, white horse leads the caravan and stands on its hind legs in a menacing stance. Behind it are elephants with tall spidery legs, each carrying a tall building full of viceful symbols. The first elephant carries a nude woman posing sensuously and touching her breasts while standing on a pedestal. The second, a tall, narrow structure like a pyramid, with four ascending circles of decreasing size. The next two elephants march side by side sharing the weight of a golden palace with an open window showing a woman’s nude body and two statues of human figures on its roof. The last elephant trails behind with a tall, round tower, whose only design is a small, dark window at the top, and is often described as phallic. Three of the elephants are taller than the white clouds. In the gray clouds on the right side, above the last elephant, is a floating castle, like heaven watching down…

I have spent a long time looking at this painting as I try to notice all of the little details. Like, why is there an angel in between the legs of the elephants? Who are the two little figures in the center: a dark figure standing in front and a figure in red who is holding a crucifix out towards the dark one, similar to Saint Anthony? Is there another tiny figure, perhaps with a dog, in the center, under one of the elephants and in between its legs? There’s also a skull by St. Anthony’s foot. Why? The large figures are easy to figure out: St. Anthony and the surrealist animals who tempt him. But, what do the other little figures show?

From my perspective, in the middle of the painting, looking up at the figures in the sky, I cannot make out what they are supposed to be. They are so tall! Are those elephant trunks hanging down? I’ll just keep walking forward and minding my business. This is a strange place to walk through with all these thin poles extending into the sky.

Reverse Ekphrasis

Source text:

But at that moment I glanced round at the crowd that had followed me. It was an immense crowd, two thousand at the least and growing every minute.It blocked the road for a long distance on either side. I looked at the sea of yellow faces above the garish clothes—faces all happy and excited over this bit of fun, all certain that the elephant was going to be shot. They were watching me as they would watch a conjurer about to perform a trick. They did not like me, but with the magical rifle in my hands I was momentarily worth watching. And suddenly I realized that I should have to shoot the elephant after all. The people expected it of me and I had got to do it; I could feel their two thousand wills pressing me forward, irresistibly. And it was at this moment, as I stood there with the rifle in my hands, that I first grasped the hollowness, the futility of the white man’s dominion in the East. Here was I, the white man with his gun, standing in front of the unarmed native crowd—seemingly the leading actor of the piece; but in reality I was only an absurd puppet pushed to and fro by the will of those yellow faces behind. I perceived in this moment that when the white man turns tyrant it is his own freedom that he destroys. He becomes a sort of hollow, posing dummy, the conventionalized figure of a sahib. For it is the condition of his rule that he shall spend his life in trying to impress the “natives,” and so in every crisis he has got to do what the “natives” expect of him. He wears a mask, and his face grows to fit it. I had got to shoot the elephant. I had committed myself to doing it when I sent for the rifle. A sahib has got to act like a sahib; he has got to appear resolute, to know his own mind and do definite things. To come all that way, rifle in hand, with two thousand people marching at my heels, and then to trail feebly away, having done nothing—no, that was impossible. The crowd would laugh at me. And my whole life, every white man’s life in the East, was one long struggle not to be laughed at.

Orwell, George. “Shooting an Elephant.” Shooting an Elephant, and Other Essays [1st American ed.]. ed., Harcourt, Brace, 1950.

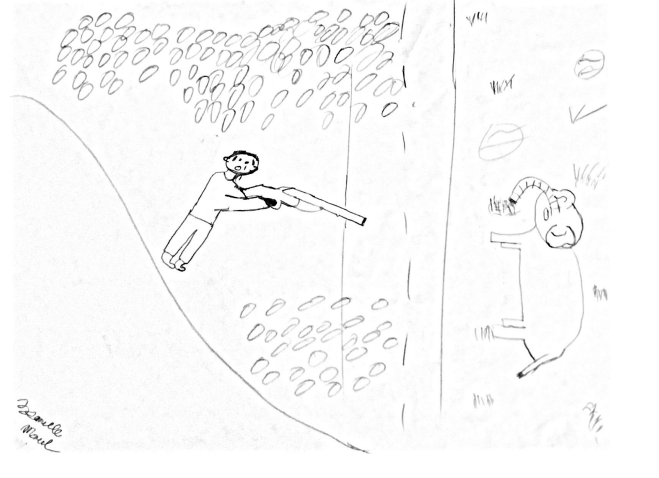

Ekphrastic drawing: