Queer Carnival

Pride festivals are celebrated in major cities across the globe. At these events, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ) people gather to celebrate community and visibly practice authenticity in public spaces. LGBTQ people are a marginalized population in society, so pride events create an abnormal atmosphere in which members of the community can openly practice their identity without fear of the violent adversity they might encounter on any other day of the year. Historically, pride events held political motives when they began in June of 1969 as a response to a violent police raid on the Stonewall Inn, a gay bar in New York City. By the 1990s, however, Pride events shifted their focus to celebrating community and practicing visible queerness in public spaces. Today, the average LGBTQ Pride festival includes a parade equipt with themed floats, performers, and marchers that engage with spectators by tossing props, ranging from flyers to condoms, into the audience. There are drag, dance, and costume competitions, LGBTQ merchandise vendors, resource booths sponsored by LGBTQ organizations, and public displays of queer affection. In this space, LGBTQ people and their allies of all ages, socioeconomic classes, cultural and racial backgrounds find themselves networking across societal boundaries and breaking heteronormative and cisnormative ideas surrounding sex and gender. In this respect, pride festivals fall within the scope of what Bakhtin would define as carnival.

The carnivalesque atmosphere of LGBTQ pride events provides for safe heterosexual participation in gay community. Pride is an inclusive atmosphere for all members of the community, local and beyond, as long as participants are respectful of each other. In “Narrating Defiance: Carnival and the Queering of the Normative,” van der Wal et. al. writes:

“Yet, it is precisely this carnivalesque difference that attracts the tourists to the Gay Village in the first place. People who would not ordinarily be seen in this space temporarily move through it and endow it with a festive atmosphere. They provide ‘exotic’ appeal for a limited period of time, and constitute visual stimulation for the tourist gaze, yet they conveniently leave after the event is finished and thus restore the Gay Village to its putative safeness and sanctity” (van der Wal et. al., 137).

Those who would normally eschew gay association can safely bring their family out and enjoy the festivities and gay culture without fearing reprisals from co-workers, neighbors and friends who may be homophobic. In “A party with politics?(Re) making LGBTQ Pride spaces in Dublin and Brighton,” Kath Browne writes:

“Thus, for some, Pride offers a respite and a chance to be ‘out’ in terms of enacting a nonheterosexual identity. The lack of fear and the opportunities to express one’s sexuality ‘openly’ for some is only possible in the ‘gay times’ of Pride and their enactments constitute Pride spaces as different from their daily lives” (Browne, 76).

As non-heteronormative identities are not only accepted but celebrated during Pride, all people can openly express homosexual affection regardless of how they choose to behave in their private lives.

LGBTQ Pride festivals create spaces in which people can express themselves and their love without fear of violence. Except for within a few cities, many people shy away from being visibly queer in public spaces because of potential adversity. On any given day, a queer couple might avoid holding hands in a park because there is no way of anticipating how a passersby might react. Will they carry on as they would if they saw a heteronormative couple or will they stop to stare at, harass, or even assault the queer couple? Pride festivals provide respite from these circumstances by creating safe homonormative spaces in which the visual perception of all sexualities are celebrated. In Music and queer culture: Negotiating marginality through musical discourse at Pride Toronto, Todd J. Rosendahl writes:

“Gay spaces, such as bars, clubs, cafes, residences, and public spaces (parades and festivals), allow opportunities for self-expression for those in the queer community . This control over a particular space is an important element of identity given that most public space is heterosexualized” (Rosendahl, 14).

Pride festivals also showcase LGBTQ bodies. In Body Acts Queer: Clothing as a performative challenge to heteronormativity, Maja Gunn writes, “Pride festival parades, which are also carnivalesque acts, have grown to become an important part of making queer bodies accepted and visible in the city” (Gunn, 208). By providing the safe space to be truly “out” in behavior and appearance, a Pride festival creates the “laws of its own freedom” that Bakhtin references when discussing the carnival (Duncombe, 86).

By disrupting the traditional order of the city space, Pride festivals succeed in becoming carnivalesque. In “Narrating Defiance: Carnival and the Queering of the Normative,” van der Wal et. al. writes

“The Cape Town Pride Parade plays itself out as a festival that has the capacity to reverse social hierarchies and cross various boundaries for a limited period of time, and thus presents itself as disruptive of normative order and social stability. Being often contradictory in nature, the carnivalesque is not only a force that can impose its own set of regulations and provide coherency for its own structures, but is also a phenomenon with the capacity to disrupt the hegemony of city space” (van der Wal et. al., 134).

Bakhtin states that these are precisely the kinds of things that the carnival succeeds in doing. It creates an atmosphere in which the traditional roles that people play in society are disregarded while people interact across boundaries that normally exist.

Some would challenge whether Pride festivals can be fairly characterized as falling within the boundaries of Bakhtin’s carnival. One reason has to do with the rising popularity of Pride and its commoditization. In 2016, over two million people came out to watch over thirty thousand people march in the New York City’s Pride Parade (Walsh, “More Than a Million”). As a popular cultural event, Pride spaces become sponsored by corporations, politicians engage, and access to certain aspects of the festival such as after parties can come with the price tag of an admittance fee. Once Pride begins charging for participation, some people from lower socioeconomic backgrounds can no longer mingle freely with wealthier patrons. “Here, in the town square, a special form of free and familiar contact reigned among people who were usually divided by the barriers of caste, property, profession, and age” (Duncombe, 88).

Once the socio-economic barriers begin to rise, Pride necessarily becomes less carnivalesque in Bakhtin’s eyes. “The temporary suspension, both ideal and real, of hierarchical rank created during carnival time a special type of communication impossible in everyday life” (Duncombe, 88). If the mayor of New York City is marching in the Pride Parade as the mayor of New York City, rather than appearing anonymously and costumed as a participant, he has maintained his profession and hierarchy among those in the festival. Once the hierarchical rank is reintroduced to the festivities, Bakhtin’s special communication is reduced. While the carnivalesque aspect of Pride may have been slightly diminished by the increasing commoditization of its space, however, the temporary suspension of rank and stature remains largely intact. People come to have fun and socialize.

Another challenge to classifying Pride Festivals as carnivalesque has to do with how you would characterize the participants. Are people there enjoying in their own release or are they merely voyeurs being entertained by the spectacle of behavior that society will only tolerate for one day? In “Gay Pride and the Carnivalesque,” Dawn Pendergast writes:

“Gay Pride also perpetuates the othering of homosexuality. By setting aside one day and place for the free expression of homosexual desire, and infusing that day with parody, cagey performance, revelry, the rest of the world watches the feathered drag queen or the topless dyke on television. The carnivalesque atmosphere may be a ‘release’ to those individuals celebrating, but the spectacle of the carnival poorly reflects the serious political and social issues inherent in sexual expression and orientations” (Pendergast).

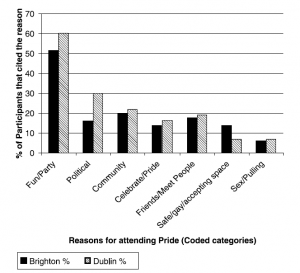

Bakhtin is quite clear on this subject, “Carnival is not a spectacle seen by the people; they live in it, and everyone participates because its very idea embraces all the people” (Duncombe, 86). Research suggests, however, that hedonism plays the primary role in Pride attendance. “Hedonism clearly has an important place in the LGBTQ Prides of early twenty-first century… The pursuit of self-gratification and enjoyment then is a strong motivating factor for a large proportion of the participants who come to ‘party at Pride,’” (Browne, 70).

While LGBT Pride festivals originally captured the essence of Bakhtin’s carnival, different influences over the history of Pride have skewed the event’s ability to remain purely carnivalesque. The primary focus of Pride is to rebel against societal norms by freely expressing non-hetero/cisnormative interpretations of gender and sexuality. This is accomplished through the festival’s visible display of marginalized gender and sexual orientations with representatives, speakers, and performers from different sectors within the LGBTQ community. As Pride events become commoditized, occupying space within the parade or an information booth comes at a cost that would not be feasible for the average participant, reserving those opportunities for local organizations and larger corporations that can secure additional funding. Pride allows for inter-community dialogue surrounding the experiences of gender and sexual minorities, but having one day or weekend designated for the inclusion of this community can result in the “othering” of this population (Pendergast). Within the context of the greater LGBTQ rights movement, this may not be the best way to approach societal inclusion. Having one day of festival allows individuals to deliberately avoid areas with greater population densities of queer people, eliminating any conversation between members of the community. While this is possible, without Pride there are very few state-sanctioned events that elevate the visibility of queer identities. To combat this “othering,” members of the community should freely and openly express themselves on a daily basis, however, this requires broad acceptance within society to occur safely. For some of the most marginalized members of the LGBTQ community, Pride is their only opportunity for visibility and it is the only event in which they can openly identify without fear of violent assault. Until marginalized communities can openly express who they are and have their identities accepted by the masses without fear of reprisals, Pride festivals will continue to be carnivalesque.

Works Cited

Browne, Kath. “A party with politics?(Re) making LGBTQ Pride spaces in Dublin and Brighton.” Social & Cultural Geography 8.1 (2007): 63-87.

Duncombe, Stephen, ed. Cultural Resistance Reader. Verso, 2002.

Gunn, Maja. Body Acts Queer: Clothing as a performative challenge to heteronormativity. Diss. Högskolan i Borås, 2016.

“More than a Million Attend NYC’s Annual Pride March.’ CBS News, CBS Interactive, 26, June 2016, www.cbsnews.com/videos/more-than-a-million-attend-nycs-annual-pride-march/.

Pendergast, Dawn. “Gay Pride and the Carnivalesque.” What Birds Give Up, D. Pendergast, 25 June 2002, http://www.whatbirdsgiveup.com/gay-pride-and-the-carnivalesque/.

Rosendahl, Todd J. Music and queer culture: Negotiating marginality through musical discourse at Pride Toronto. The Florida State University, 2012.

van der Wal, Ernst, and Lize van Robbroeck. “Narrating Defiance: Carnival and the Queering of the Normative.” (2010).

Walsh, Shannon M. NYC Pride Parade Attendance: How Many People Are Expected to Attend? Heavy, 25 June 2017, heavy.com/news/2017/06/nyc-gay-pride-parade-attendance-how-many-people-attend-number-statistics-2017/.