Finding Carnival in Silence

When visiting a museum, you expect to see artwork throughout the building. When going to a sporting event, you expect to see athletes compete against one another. When going to a concert hall, you expect to hear an artist perform music. So, when the virtuoso pianist David Tudor sat down at the piano to play a piece composed by John Cage at the Maverick Concert Hall in New York during a recital for contemporary music on August 29, 1952 and played no music for four minutes and thirty-three seconds, the audience felt like they had been cheated of a performance and exploited by Cage.

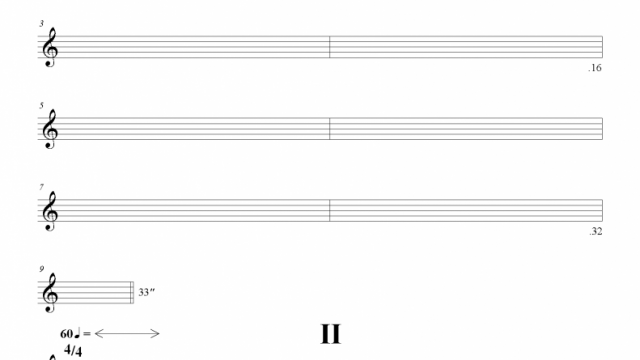

The Sheet Music for “4’33″”

This performance, known as “4’33””, is the composition of silence. Or, more accurately, the music that is found with the absence of conventional music. At its first performance, Tudor sat down at the piano onstage, and over the course of four minutes and thirty-three seconds, opened and closed the piano lid three times before standing up and exiting. John Cage scandalized the audience by producing an arrangement that had no music. Instead, the piece was composed of any and all ambient noises heard in the concert hall during the three movements. The audience’s rearranging, coughing, stomach rumblings, sniffling, scratching, quiet murmurings, and movements, along with the shutting of doors, rain pattering on the rooftop, and footsteps of audience members leaving the concert hall was the music of the piece. By allowing the audience to create the music, John Cage successfully broke the barrier that existed between the performer and the audience. For the four minutes and thirty-three seconds that Tudor sat at his piano, the ordinary divide between spectator and performer no longer existed. There was a second, upside-down world that was created within the space of the concert hall due to the effects that the composition had on the audience. This alternative world and the conditions created within it were very similar to what the Russian philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin wrote about when describing the carnival of the Middle Ages and Renaissance in his book Rabelais and His World. Carnivalesque features can be expanded to, as M.D. Fletcher argues, “all cultural situations where the authority of a single language of authority is called into question, notably by the simultaneous copresence of other languages, which can challenge it’’ (Fletcher 23). By challenging the authority of music with silence within the concert hall, “4’33”” becomes an unlikely modern-day carnival.

The Maverick Concert Hall

Bakhtin claims that the rowdy nature of the particular celebration, festivities, and events of the medieval carnival created a second life that represented a liberation from everyday social hierarchies, rules, and norms that allowed for social cohesion through the behavior of the citizens. A carnival democratized culture through the universal, mass contribution of the breaking the rules and social norms of conventional life. The carnival “celebrated temporary liberation from the prevailing truth and from the established order; it marked the suspension of all hierarchical rank, privileges, norms, and prohibitions” (Bakhtin 87). At the carnival, the king was decrowned and became the fool, the fool was crowned king, and there was the free and eccentric interaction between all different types of people. Although the composition does not share all the characteristics of a carnival, it shares a surprising amount. Silence is not the rowdy fun traditionally associated with a carnival, but by democratizing culture within the concert house, the composition inspired many of the same cultural results of the traditional medieval carnivals that this theory is based off of. Thus, “4’33”” can be considered a modern-day demonstration of carnival due to the transformational nature of its performance.

When the composition begins, rapid changes occur within the concert hall. The audience members, expecting a masterpiece to be performed, are confronted with silence. They themselves begin to create the piece with the performer onstage. Instead of controlling the instrument and the sounds that are produced, the performer must relinquish her power as the sole composer and include the audience and their surroundings. Thus, “4’33”” undoes the ordinary divide between the performer and spectators within the concert hall by allowing both the audience members and the performer to compose the music together. In the concert hall, there is no differentiation between the performers and the audience.

The carnival relied on a “suspension of all hierarchical precedence” so that “all were considered equal during carnival” (Bakhtin 88). Just as the king gave up his crown at the carnival, the performer in “4’33”” relinquishes her power to control the music and transcends her role as the king by allowing the audience to create the music with her. “4’33”” does the work of the carnival: it “does not acknowledge any distinction between actors and spectators” (Bakhtin 86). Therefore, equality is ensured since the composition makes everyone the authoritarian composer and the active listener. The composer – the king – decrowns himself and reverses traditional power structures since his spectators are now his equals. In “4’33”” however, there is one necessary power that the performer must retain: the ability to control time. The medieval carnival atmosphere did not last indefinitely. Rather, it was effective at democratizing culture because of its temporary state. Similarly, in “4’33””, the performer needs to have the ability to control the space and time so that this modern-day carnival can occur.

The carnival quality of universality can also be found in the performance of “4’33””. By reversing the social hierarchies of everyday life to create equality, the carnival allowed for universality in participation. No matter class, race, or age, all were allowed and encouraged to participate. The “carnival is not a spectacle seen by the people; they live in it, and everyone participates because its very idea embraces all the people” (Bakhtin 86). In “4’33””, mass participation is not a choice. Just by being in the concert hall, the audience contributes to the carnival. Social hierarchies no longer matter since the everyone from the wealthiest guest sitting in a box to the poorest guest sitting in a restricted seat in the very last row of the hall are a participating member of the carnival. Everyone contributes by clearing their throat, gently repositioning, and even breathing during the four minutes and thirty-three seconds they are sitting in the concert hall. Even when leaving the concert hall, all are adding to the music through their footsteps, apologies to the other guests when they pass by them in the row to exit to the aisle, and the sound of the door opening and shutting behind them. Just like at the carnival, during a performance of “4’33”” all members join together to create this upside-down world where all are considered equal.

An example of a traditional concert hall.

Carnival is not just a deconstruction of societal norms, but a place where rowdy fun, chaos, and the grotesque are encouraged and expected. Most every and all forms of behavior are permitted, since it was a time for rules to be broken. The carnival is defined by festivity. Although it might not seem like a concert hall is the setting for these types of behavior, essences of these qualities can still be found today within “4’33””. Ordinarily, there is a strict etiquette for a concert hall, which includes staying as silent as possible during a performance. The carnival, on the other hand, “is the people’s second life, organized on the basis of laughter” (Bakhtin 86). Whereas rude, loud, and obnoxious behavior is common at the carnival due to the rowdy fun, it is unacceptable at a concert hall. If someone needs to cough, she is expected to hold out until a loud point in the piece and make it as silent as possible. Yet, the feelings associated with rowdy fun of the carnival is found in the humor and irony of a performance of “4’33””. Instead of getting to listen to a master pianist perform, the audience gets to sit awkwardly in their seats for what feels like an infinity, listening to the ambient noises of the other two hundred people in the concert hall. The performance can feel like a comical mockery of the concert hall, by being a celebration of what is not official. The music is official, the silence is not. Thus, by creating a musical composition out of silence and forcing the spectators to listen to the ambient noise, “4’33”” mocks the officiality of the strict social norms of the concert hall.

Furthermore, the grotesque quality of a carnival can be found in “4’33”” because, by relying on the sounds of bodily functions to create music, it transgresses the boundaries between life and art. A carnival “belongs to the borderline between art and life. In reality, it is life itself” (Bakhtin 86). The performance of “4’33”” is dependent on the body and the sounds it creates. Both the sounds created by a spectator pass gas during a performance and the accompanying laughter is the music the audience has just paid to listen to. The experience of being united through these bodily functions promotes a cohesion throughout the concertgoers that is unique only to its carnivalesque quality. These sounds create the grotesque realism that is a key characteristic of the carnival because, as Ross Singer writes, it “promotes laughter in a way that does not invite an alienating gap between audience and performer… it is an ambivalent laughter that expresses recognition of human connectedness, rather than private individual reaction to the whole world” (Singer 137). Instead of being scorned for coughing during a performance, “4’33”” creates an ironic, unified, upside-down world where those sounds are necessary and indispensable because they form the basis of the music. Grotesqueness facilitated the departure from the conventional concert hall etiquette as another way equalize the audience. By emphasizing the body and its uncomfortable, yet amusing functions, the performance takes on a grotesque quality, albeit to a much smaller degree than a traditional carnival.

Like a medieval carnival, the performance “4’33”” provides an alternative social space where the participants find a world turned upside-down. By providing an imaginary suspension of the modern power structures of social hierarchies, having universality in participation, mocking the official notion of a concert hall, and having a grotesque quality, the composition “4’33”” creates a temporary carnivalesque condition by democratizing the culture within the concert hall.

Works Cited

Fletcher, M. D. (1987). Contemporary political satire. Lanham, MD: University Press of

America.

Mikhail Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World, Helene Iswolsky (trans.), Bloomington: Indiana

University Press, 1965/1988, pp. 4-11.

Singer, Ross. “Anti-Corporate Argument and the Spectacle of the Grotesque Rhetorical Body in

Super Size Me.” Critical Studies in Media Communication, vol. 28, no. 2, June 2011, pp. 2-1-2-18. EBSCOhost doi: 10.1080/15295036.2011.553724.