Bob Marley: (Groundless) Proof that the White Westerner is not Racist

In the style of David Foster Wallace

Edited by Meghan Voss

Just so you know, right off the bat, I’m going to be using this term “White Westerner.” It’s not a real term, like White American, but it suits the group of people I’m talking about better, and I wanted it to retain the extra zing that comes with the capital letters. And by the way, I mean Westerner as an inhabitant of the Western World. So, you know a lot Westerners than your freshman roommate who dropped out and moved to Arizona and became a yoga instructor. Specifically, I’m going to be talking about White Westerners’ peculiar adoration of Bob Marley. I’m going to be arguing that Marley’s ethnicity is of as much intrigue to White Westerners as is the quality of his music. I’ll be asserting that White Westerners have perpetuated stereotypes about Bob Marley in order to increase his perceived blackness and Jamaicanness. I will also contend that part of the reason Marley is so popular with White Westerners is that he and his music have certain white features, not consciously registered by White Westerners, that make them more comfortable with a man of his ethnicity, despite the fact that his ethnicity is a large part of the appeal in the first place.

There is a significant gap between how much White Westerners actually listen to Marley and how much they worship him. For example, White Westerners buy Bob Marley T-shirts, hats and posters in far greater quantity than, say Elton John merchandise, even though the latter is decidedly more popular in the White West in terms of record sales. This is because they want everyone to know they listen to a Jamaican, not another white dude from Middlesex. Marley is the token Caribbean artist of interest to White Westerners. He adds an element of cultural flair to their musical diets of Billy Joel, Dire Straits and Aerosmith, or U2, R.E.M. and Radiohead.

White Westerners are not so much interested in Marley’s music as they are in creating an association between them and a Jamaican, however feeble that association may be. I’m going to make up another term, the ethnicity expansion reward, to describe the psychological benefit White Westerners receive by connecting themselves with foreign ethnicities, especially if that includes non-white races. The ethnicity expansion reward comes from a few sources. Bell hooks’ idea that the consumption of ethnic cultures provides a release from the constraints of whiteness holds some weight. But even more so, the ethnicity expansion reward stems from the common fear that White Westerners have of being accused of racism or bigotry (even if the accusation comes from oneself in the form of doubt over one’s tolerance). This fear stems from the fact that white people have been enormously, inordinately, preposterously racist for their entire existence, historically slaughtering, enslaving, abusing and segregating every race other than their own. After centuries of getting off scot-free, they are finally being called out for it. Hua Hsu captures the feeling many white people have today of being under attack for their race’s wrongdoings in his provocative essay, “The End of White America?” He quotes Bill Imada, founder of the IW Group, who says, “I think white people feel like they’re under siege right now–like it’s not okay to be white right now, especially if you’re a white male” (Hsu, 503). “I really feel like the hunted,” says a white man, “It’s a hard time to be a white man in America, because I feel like I’m being lumped in with all white males in America” (Hsu, 503). Today, having accepted the historical and contemporary oppression by the white man, and carrying a deep-seated sense of both guilt and fear for being a member of this oppressive group, an accusation of racism carries a special string to both the personal psyche and public reputation of a White Westerner. Hsu points to Williams “Upski” Wimsatt’s 1994 book Burn the Suburbs as an example of how the white ideology has shifted towards rejecting its own race and praising others (Hsu, 503-504). In the eyes of the White Westerner, interacting with and championing other ethnicities serves to prove they are not racist, or at least help the cause. Consider the classic, though hilariously misguided, White Western defense against an accusation of racism: “I have (a) black friend(s).” Or, even more harmful, the insensitive tourist who thinks “I have a real appreciation for these island people after listening to Bob Marley.”

In order to ensure their association with a Jamaican is in no way tainted–that they are interacting with a “true” Jamaican–so as to maximize their ethnicity expansion reward, White Westerners have taken special note of, and been sure to advertise, certain stereotypes they find present in Marley. In order to maximize Marley’s perceived Jamaicanness, Caribbeanness and blackness, they have flaunted the following stereotypes: poverty, marijuana use, Rastafarianism, a laid-back lifestyle and various physical attributes.

Essential to Marley’s fame among White Westerners is that he fits the stereotype of the poor, black (or Jamaican) man. To White Westerners, a wealthy black man is not really a black man, or at least not as much of one as a poor one is.

Another stereotype about black people, and especially Jamaicans, is that they love marijuana. While marijuana was an important part of Marley’s religion, and thus, his life, it was rarely mentioned in his music, save for a couple of tracks he recorded in his pre-international fame days in Jamaica. Regardless, White Westerners have played up Marley’s consumption of marijuana to an extraordinary degree. Marley’s image has been attached to everything relating to weed: bowls, bubblers, bongs, rigs, one-hitters, vaporizers, rolling papers, blunt wraps, grinders–you name it. There’s even a popular strain of marijuana bearing Marley’s name. There isn’t a person in the Western world whose name is more frequently associated with weed than Bob Marley.

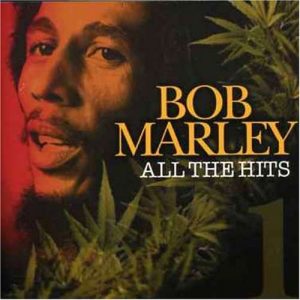

Even a popular Marley greatest hits album bears the Jamaican colors, along with a prominent display of marijuana

The tremendous focus White Westerners have put on Marley’s Rastafarianism also acts to increase his Jamaicanness. Christianity, the predominant White Western faith, “is visualized in white terms” (Manley, 2). Every essential character in the Bible is portrayed as white, including God and Jesus. Rastafarians, on the other hand, have an African man, Haile Selassie, as their savior, and their God, Jah, is depicted as black (Manley, 2). Before the recent advent of trustafarians–rich white folks who go around acting like Jamaicans–Rastafarians were entirely black Jamaicans. So, the fact that Marley was a part of this strange, ethnic religion adds to his Jamaicanness. Jamaican scholar Rex Nettleford identifies Marley’s Rastafarianism as the most important factor in his success (Manley, 4). Marley’s religion is so crucial, Nettleford argues, because it gave reggae music an underlying philosophy that the whole world could unite around (Manley, 4). The idea that White Westerners were so moved by Rastafarian objections to African diaspora and oppression that they’ve made Marley one of the central figures in music paints a utopian view of the capacity of White Westerners to sympathize with black people. Nettleford is correct, Marley’s Rastafarianism is a key factor in his global popularity, but as far as the White West is concerned, it’s simply another way of increasing his ethnicity.

There’s also the White conception of black people as lazy, and Jamaicans specifically as having a laid-back lifestyle. The latter stereotype is partly the doing of the Jamaican tourism industry, which has seen that visitors react well when they present themselves as easygoing. It’s also related to the aforementioned marijuana stereotype attached to Jamaicans. Whatever the cause, there’s no question that a relaxed “No problem, mon” has become the iconic Jamaican phrase in the minds of White Westerners. Demonstrating Marley’s attachment to the laid-back lifestyle is as easy at looking at what has become his most recognizable song among White Westerners: “Three Little Birds.” This song contains some of Marley’s most beautiful poetry. The two verses in the song go: “Rise up this mornin’/ Smiled with the risin’ sun/ Three little birds/ Pitch by my doorstep/ Singin’ sweet songs/ Of melodies pure and true/ Saying’ (this is my message to you).” The image of waking up with the rising sun to three birds tweeting along on your doorstep makes the listener want to smile along with Marley. But this part of the song, where the title is derived from, is all but ignored by White Westerners. That’s because the big sell is the chorus: “Singin’ don’t worry/ About a thing/ ‘Cause every little thing/ Is gonna be alright.” Because to them, that’s what Jamaicans do: roll up a joint, take a seat on the sand under the bay moonlight, and listen to the waves crash, not a care in the world.

Marley’s physical appearance is also of great interest to White Westerners. His dreadlocks–a hairstyle almost exclusively associated with black people until trustafarians started getting their blond hair braided–have become a symbol for his blackness. The green, yellow, red and black “Rasta hats” that Marley occasionally donned have become an even more famous representation of his Jamaicanness. This is why Marley is often portrayed wearing one, even though he so rarely did in his lifetime. More broadly, the colors green, yellow, red and black are usually incorporated into White Western depictions of Marley as yet another reminder of his ethnicity.

To demonstrate the importance of these stereotypes in disseminating Marley’s fame among the White West, suppose Marley was born to the owner of a successful plantation. Suppose he had a buzzcut, was Catholic and hated weed, and that he was known as an anxious guy, constantly preoccupied with worries about his demanding performance schedule, contractual obligations, catching the bus, remembering if he left the stove on, how damn difficult it is to open pistachios sometimes, etc. Suspend the constraints of logic and suppose as well that Marley’s body of music was identical. Having lost the stereotypes that make his ethnicity so flauntable, I’d be willing to bet the dreadlocks off of every trustafarian’s head that White Westerners would be a whole lot less excited about listening to his music.

Unbeknownst to White Westerners, both Marley and his music were naturally quite white. These white traits made him more appealing to White Westerners. With Marley, they could get their ethnicity expansion reward without having to suffer through something truly ethnic.

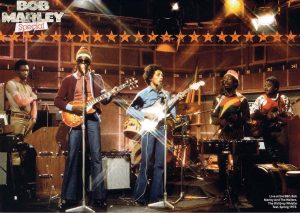

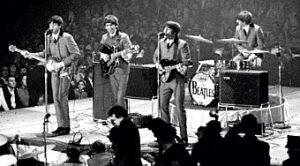

For one, while Marley was playing reggae, a distinct Jamaican genre of music, there were unmistakable elements of rock, R&B and doo-wop–styles that White Westerners had been comfortable with for years before discovering Marley–built into it. Even though all three of these genres trace their roots to African-Americans, by the early ‘70s, they had for more than 15 years been the central part of the White Western musical tradition. Reggae, the new genre that artists like Bob Marley came to define, arose from ska. Ska, in turn, is “a sort of marriage between American Rhythm and Blues, (American) Gospel and the indigenous mento form” (Manley, 2). In other words, the musical base of reggae is two-thirds American. Manley points out that because of African diaspora, the art of African drumming is completely lost in ska and reggae music, which instead adopts R&B drum beats (Manley, 2). In the transition from ska to rocksteady to reggae, led by Bob Marley, popular Jamaican music began to incorporate even more elements of American music, most noticeably heavy use of the electric guitar. Indeed, the fact that Marley had been doing Beatles covers from a young age says a lot about the kind of music he made.

The similarities between Bob Marley and the Wailers and Western rock bands are visually evident

Marley’s biggest hit among White Westerners is Exodus, which bears perhaps the most famous b-side in music history: “Jamming,” “Waiting in Vain,” “Turn Your Lights Down Low,” “Three Little Birds” and “One Love/People Get Ready.” Not coincidentally, this is also the Marley album with the most familiar sounds to White Westerners, in that Exodus is as much the blues, soul and rock as it is any form of Jamaican music. In his examination of the album, joshuatree, and emeritus from Sputnikmusic, concludes, “Exodus is much more rooted in the blues and soul, has a little pinch of the British rock that much of his fanbase was also listening to, with a reggae façade thrown on top” (joshuatree, para. 5).

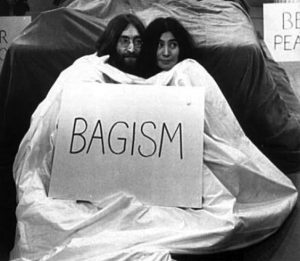

On top of that, by the time Marley rose to prominence, rebellion was the word in Western pop culture. With records like “Get Up, Stand Up,” “Soul Rebel” and “Redemption Song” catching fire, Marley clearly fit in as another anti-something, like Dylan, Lennon and Cash. His particular branch of rebellion was particularly attractive, as by the early ‘70s, most White Westerners were attaching themselves to the hip new idea that black people should have equal rights. His cries for freedom were eaten up by this emerging white market. “The greater part of Bob Marley is the language of revolution,” notes Manley, “…It is this, possibly, which sets (reggae) apart even to the international ear” (Manley, 3).

Best of all, Marley was half-white. So while he could still be flaunted as a negro, he lacked that offensive, often downright terrifying dark brown skin tone.

When White Westerners think of David Bowie, they think of his extra-terrestrial persona and lyrical themes, his catchy, but difficult to reproduce melodies, his tremendous impact on punk. They think of a music and performance god. Certainly, nothing of his “normal” British ethnicity comes to mind. But when White Westerners think of Bob Marley, whose breadth of music and scope of influence surpasses even Bowie, they think of great reggae, yes, but just as much they think of his ethnicity, supported by stereotypes of poverty, marijuana use, Rastafarianism, a laid-back lifestyle and his physical appearance. There is a seeming paradox in the White Westerner’s love for Bob Marley: special attention is given to the fact that he is of an oppressed race, and that black Jamaicans, specifically, are a population of former slaves, yet Marley’s similarities to White Western culture make him more appealing to the White Westerner. Overall, White Westerners are as interested in the guise of tolerance of other ethnicities that listening to Marley provides them with as they are in his actual music.

Works Cited

Hsu, Hua. “The End of White America?” The Atlantic, Jan.-Feb. 2009,

http://tylerthompson.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/93141039/. The%20End%20of%20White%20America%20-%20Hua%20Hsu.pdf.

Accessed 12 Dec. 2017.

Joshuatree. “Bob Marley and the Wailers Exodus.” Sputnikmusic, 9 Jan. 2008,

www.sputnikmusic.com/review/14837/Bob-Marley-and-The-Wailers-Exodus/.

Accessed 12 Dec. 2017.

Manley, Michael. “Bob Lives.” Rising Sun [Kingston]. National Library of

Jamaica, http://www.nlj.gov.jm/files/u8/bn_marley_rn_001.pdf. Accessed 12 Dec.

2017.