Check out our anti-capitalist, anti-racist comic strip: Wall Breakers! It explores the cyclical nature of racism, sexism, and classism as they intersect in the virtual and “actual” worlds – playing themselves out in much the same way that we “play” video-games.

Wall Breakers Structural Analysis

Sequencing:

The Photo: A white boy finds a Black girl (Lucy) in the library who piques his interest. He creepily (and non-consensually) takes a picture of her.

The Door: Lucy finds herself suddenly in an empty, all-white space. She finds a red door (with a A button for a doorknob) and runs towards it. She opens the door to find herself in completely new place: Attica – a video game.

The Arms Dealer: Lucy meets a Black man who is selling weapons. His repetitive speech patterns lead Lucy to the conclusion that she is now inside a video game/virtual reality.

The First Boss: The Arms Dealer leads Lucy to the First Boss – an East Asian woman stereotypically dressed in a red & gold martial arts robe. Lucy is forced to fight the First Boss and quickly kills her.

The Final Boss: Another red door mysteriously appears. It leads Lucy to The Final Boss (who looks exactly like the white man from The Photo scene). He is sitting in a chair associated with Wall Street. Lucy tries to stab The Final Boss, but there is a mysterious force-field around him. She breaks her sword trying to stab him. The screen says “Game Over.” The end credits roll and Lucy is returned to Level 1. She tries again and again and again…

The Arms Dealer Part 2: Lucy approaches the Arms Dealer again. This time, she flipping back and forth between the menu options “buy, steal, trade” so that the Arms Dealer glitches. The Arms Dealer is freed and thanks Lucy profusely. He joins her on her quest to kill the Final Boss and escape the “game.”

The First Boss Part 2: Lucy and The Arms Dealer refuse to bow to The First Boss. They wait for hours and hours until she glitches and “breaks free” of her controlled, avatar body.

The Final Boss Part 2: Lucy walks back and forth across the threshold of the Final Boss’s office, so that he is forced to keeping turning around in his black swivel chair. He ultimately glitches and disintegrates entirely. Color returns to the scene/story and Lucy, smiles, holding her own crumbling image in her hand.

Structural Analysis

Wall Breakers plays with the images that invade our virtual and actual realities, drawing connections between modern-day imaging technologies and the long-standing history of using images to manipulate and exploit people of color (PoCs). In Wall Breakers, we flip the script. The real world is often portrayed as a prison, whereas the virtual world, and videogames (like GTA5), are often portrayed as a separate sphere allowing for freedom and fantasy.

In this story and structural analysis we juxtapose the first and final scenes of Wall Breakers to explore the ways in which the virtual world mirrors the incarceration of the “actual” world – especially the incarceration of people of color.

In the first scene, a white man with exaggeratedly Aryan features (bright, blue eyes and bleach, blonde hair) captures Lucy’s image without her consent, using the facial recognition technology on his iPhone.

Before Lucy is ever even transported to Attica (the video game world, aptly, is named after the real-world prison where the world’s most famous Prison Uprising took place) she is trapped within the four, black walls of the iPhone’s case. In this way, we can see that imaging technology is its own kind of prison. In this scene the overwhelming whiteness of the page – and the photographer/game creator (who is wearing a white hoodie) – is contrasted by Lucy’s bright, yellow shirt – a colorful light encased in the four “walls” of the iPhone’s case – floating in a sea of white space, representative of the power dynamic at play between white and black, male and female characters.

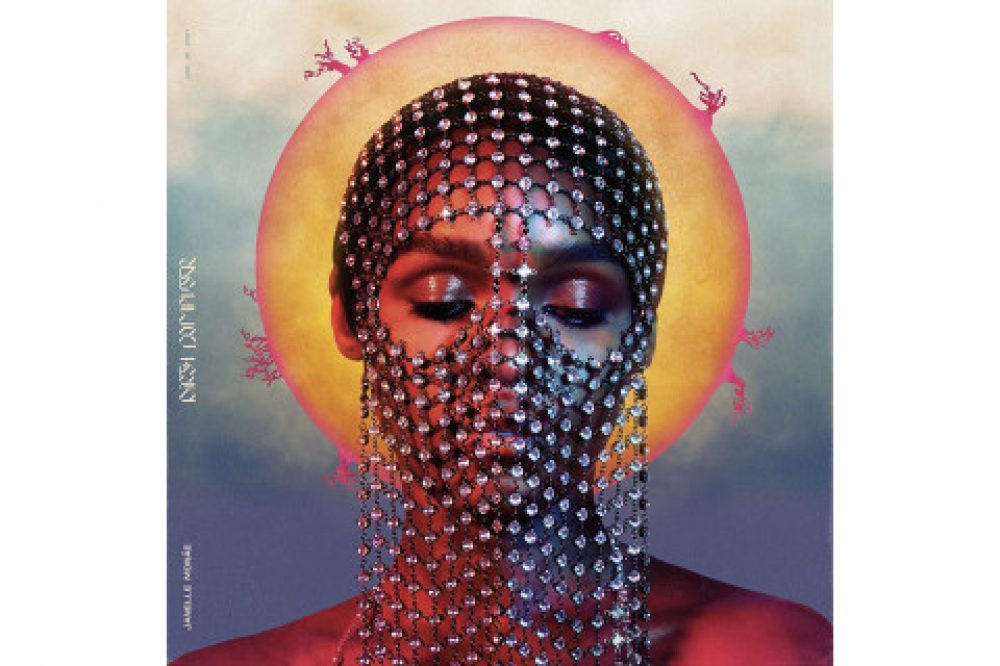

We deliberately chose to make Lucy a Black woman because even when Black women are “included” in video-games, they are rarely the ones creating and defining the story or being catered to as its primary consumers/players. We were inspired by Black Mirror’s episode “Black Museum” where Nish – a tech-savvy Black woman – frees her father (a Black man) and the other women and PoCs who’ve been encased in Rolo Haynes’ museum primarily for the viewing “pleasure” of other wealthy white men.

In the final scene, we see Lucy’s arm protruding triumphantly from the bottom of the page. Her arm – raised, perpendicular to the page – is reminiscent of the Black Power fist. In this scene, she holds onto the same image from the first scene (her OWN image). In this way, we see that, collectively (with the help of the other PoC characters), she is able to reclaim her own image, and dictate the circumstances under which it will or will not be disseminated.

This reclamation reintroduces color into what was initially an all-white scene. Importantly, the final scene is filled with various shades and hues that are richly connected to the intersecting identities of the WoC characters (Lucy and The First Boss). As her image/avatar shatters, Lucy’s background shifts from light to dark purple – although this was the color of her hyper-sexualized costume, here, it takes on a different connotation, one which harkens back to Alice Walker’s famous quote “Womanist is to feminist as purple is to lavender.” She seems to be embracing an image that is no longer tied to the whiteness and maleness of the Final Boss who first non-consensually captured her picture.

The cyclical nature of video-games and the limited options available to players/avatars make them perfect metaphors for real-life cycles, like the cycle of poverty that we see Lucy studying at the beginning of the story. But, in this final scene, we wanted to reinsert Lucy’s agency. She – like us – is not bound to repeat the same stories and use the same technologies. She can rewrite the story – or refuse to play with existing systems of power.

Gaming & Avatars: The Raced, Classed, and Gendered Nature of GTA5

I’ve never played (or, even, considered playing) GTA, despite the fact that it’s the highest grossing videogame in world history. I wanted to figure out why I had never had the urge to play GTA, so I turned to Rockstar Game’s branding of GTA5 to see who, exactly, they were marketing to. What I found was that they were, clearly, marketing to men. In every official GTA5 trailer, women were either excluded or included only insofar as they fit a hyper-sexualized, hyper-critical stereotype of what women embody.

Although the videogame, undoubtedly, dismisses and dehumanizes all women, the ways in which it does this seemed to differ along racial (and economic) lines. Wealthier, whiter women were featured in “bickering” scenes where they embodied the hysterical, needy/nagging wife stereotype. In one trailer a white, woman screams, “I hate you” at Michael and, in another scene the frivolity of her hatred is illustrated by the fact that she screams “Stop it. You’re ruining my yoga” (7:54), as if her anger about his verbal and physical abuse is actually only a silly, superficial argument about interfering with her low-key problematic, leisure activities.

Both similarly and dissimilarly, Black women filled stereotypes like the ABM (“angry black woman”) that were distinctly tied to their Black femininity. They were primarily portrayed stripping and emasculating Black men, like Franklin, by screaming things like, “You ain’t changing,” an accusation that is easily (mis)read as “overreacting” by viewers and players who are, naturally, attuned to the emotions of their avatar (Franklin). Since the game is centered around three, quote-un-quote “diverse” men (Michael, Franklin, and Trevor) the viewer/player is always encouraged, like the camera, to take their point-of-view. As a player you inhabit, or adopt, the body and personality of your avatar, acting vicariously or – as the trailer puts it “voyeuristically” – through their body. This can be seen as both a freedom and an unfreedom because, in an open-world game you, hypothetically, choose what you and your avatar do, but you’re also constrained to the hyper-masculine personality and male-presenting body that GTA provides you. Although these men are seen hitting and assaulting the women of San Andres, we – as viewers and players – are primed to downplay the implications of these actions, because WE are the ones doing the hitting and assaulting, and it is our story/personality, not the story or personality of these secondary characters, that we see and are, thereby, primed to relate to.

Interestingly, although the game features two white, male leads, the racial and cultural coding of Los Santos (and the fact that they work in the underbelly of the city) make their actions seem more connected to inner-city, immigrant communities, than their own overwhelmingly white residencies. Los Santos is an obvious allusion to Los Angeles, a connection that is made even more explicit through the Vinewood (read Hollywood) sign we see in this “imaginary” city. This allusion automatically connects the violence associated with Los Santos to Latinx/Spanish-speaking communities, even as we see that violence enacted by Franklin and the two, white male leads.

This implicit racism and classism is also embedded in the set-up and soundtrack of the movie. The backstory for GTA5 is that Michael (the former, singular protagonist of the franchise) wants to “retire” from a life of crime to – as he puts it – be a good man, a family man. Naturally, Michael doesn’t succeed because the game requires that players engage in illicit, even, immoral activities. But, it’s interesting that the two new characters, Franklin and Trevor, are the ones who, ostensibly, drag Michael back to the streets. Franklin, a lower-class Black man, and Trevor, a lower-class white man, are both less privileged than Michael. So, it seems that, while we might believe that Michael is “redeemable” (after all he tried to be a “good guy”), the game argues that Franklin and Trevor will always be “bad guys” and may even suck unwitting wealthier, whiter men into their unsavory activities.

Their connection to the world of crime always seems like an individual choice – as opposed to a consequence of their respective race and class status. This is a theme that runs throughout the trailers for GTA5. For example, in one trailer we see a homeless man holding a sign that reads, “Need money for beer,” a statement that reinforces the classist (and often racist) assumption that people experience poverty because of their own “poor” life-choices (i.e. spending money on alcohol instead of more “sensible” things). This refusal to acknowledge the structural nature of poverty goes hand-in-hand with GTA5’s problematic presentation of “the city.” Urban decay is juxtaposed with the sublime beauty and majesty of nature (7:18). This positions the inner-city as a place that needs escaping, rather than fixing, in much the same way that GTA5 labels the low-income, people of color (those who primarily inhabit the inner-city) – as irredeemable “tragedies,” rather than the natural outgrowth of an unequal, unsustainable system that could be reimagined. In Franklin’s trailer, we see one Black man deride him for “choosing” a life of gangbangin, while another Black man argues that “Gangbangin’s all we got. That’s our heritage.” (4:40). But, both statements seem to miss the mark, either suggesting that gangbangin is an individual choice or an unavoidable, outgrowth of the fact that Black communities are totally deprived of role models. This leaves me wondering where all of the legendary Black freedom fighters, protesters, thinkers, singers, writers, and dreamers went. This second Black, man’s assertion suggests that Blackness is solely defined by so-called “black-on-black crime,” rather than illustrating that this violence is only part of the story. When we define a whole people by one aspect of their struggle, as Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie argues in her TedTalk, we deny Franklin (and Black men like him) the multiple histories and heritages that he has to choose from, again contributing to a narrative of Black “irredeemability.”

Race is deeply essentialized in GTA5 and signified, most prominently, through the soundscape of the game. “Hood Gone Love It” plays during Franklin’s trailer, and, despite the fact that “freedom of choice” is a major selling point for GTA5, Franklin seems bound to a particular type of “urban” branding. He is seen choosing between several, streetwear-style jackets as the narrator speaks about the ability to customize your character. But, it seems that, although the viewer can, allegedly, say whatever they want and buy whatever they want, the way that they say what they say and the style of the thing that they buy is relatively fixed. In other words, Franklin will always speak in the street slang typically associated with the particular brand of urban, blackness that he is supposed to embody. Similarly, the soundscape serves to racially, economically, and geographically code Michael and Trevor’s characters. Michael’s trailer is accompanied by the familiar soundtrack of Queen, jiving well with the “rich,” white, cosmopolitan man he is portrayed to be, whereas Trevor’s country soundtrack: “Are You Sure Hank Done It this Way,” screams uneducated, unsophisticated “hillbilly,” a stereotype of lower-class “white trash” that is reflected in his vulgar speech (6:13).

Last, but not least, I would argue that the very premise of the game is problematic in that it posits that “ghetto life” is a game, something that white, wealthy players can turn on and/or off. This, too, is achieved sonically. The upbeat soundtrack in all of the trailers reinforces the idea that the violence some people (mostly low-income, people of color) face involuntarily is a game – a pleasurable activity that can be voluntarily played by people who will never have to experience the very real PTSD that accompanies living in a space where you are constantly safeguarding your body and your property.

Online Dating

I’ve never dated online, mostly because I’ve been in a longterm relationship for the past four years, but also because (aside from being woefully bad at technology) the snap judgements demanded of people when “online dating” scare me. Oftentimes, dating apps (despite flashy, “multicultural” ads that imply otherwise) actually accentuate the identity-based assumptions we make in real life (irl), providing a conduit for our most racist, sexist, classist, ableist, and transphobic selves to “shine” through, swiping left on anybody who doesn’t, immediately, meet our preconceived notions of a what a partner “should be,” notions that are always inflected by implicit biases.

But, I also think that not having to subscribe to online dating sites is, in itself, a privilege connected to the ways in which white femininity is idolized in U.S. society and my pansexuality broadens rather than narrows my possibilities. If it is unlikely that you will be able to find suitable dating partners/prospects irl because you are a member of a minority group, whether you identify as a racial and/or sexual minority, then online dating may provide ways for you to connect with other queer people and/or black people. This helps to expand the pool of dating possibilities beyond the people you would ordinarily “bump into.” Of course, entering these cyber worlds never allows an actual reprieve from the real world, and, like “real life” is beset with issues and ethical inquiries.

As co-chair of Converging Worlds, I help to facilitate pen pal relationships between students at Williams College and incarcerated (often LGBTQIA identified) people on the Black and Pink database. I often think about what it means that students can choose to narrow their search for a suitable pen pal by checking off various identity and interest-based boxes (especially since there is an inherent power asymmetry between people in the free world and people in prison, the people choosing pen pal and people being chosen). On the one hand, identity-based markers can enable students to more easily connect with people who share certain, salient identities and interests with them, helping to bridge the gap between two people in disparate places and positions. On the other hand, this feature enables choosers to systematically exclude people with certain identities or interests. We know, from statistical and anecdotal research, that the people most often excluded are the people most marginal to U.S. society (trans folks, trans folks of color etc). Another issue with this feature is its ability to enable fetishization because when somebody does choose markers of marginality to narrow their search (unless they share those markers) they are, primarily, choosing somebody based on a snapshot image of what that identity means, rather than the individual’s personality. This feature has both pros and cons, like any piece of technology, and its effect is, ultimately, dependent on how it is used. In the end, online dating is just a projection of dating irl, one which carries whatever assumptions and prejudices we, consciously or unconsciously, carry with us.

Structural Analysis of 28 Days Later

Here’s a brief overview of 28 Days Later, feel free to skip down to “the good stuff” if you’ve already seen it.

The Rage! Three white animal rights activists free “chimps” from captivity at the Cambridge Primate Research Center. They accidentally release “Rage,” a cannibalistic “disease” that the chimps have developed in the laboratory, presumably from watching images of human violence on TV. The chimp’s first kill is a white woman.

The Hospital 28 days later… Jim (white) wakes up from a coma to find that the hospital and country have been deserted. He visits a church, where he encounters an infected priest, and narrowly escapes with the help of two survivors: Selena (black) and Mark (white), who show him their hideaway.

The Family Jim visits his family and finds that his parents have committed double suicide. He (stupidly) lights a candle, alerting “the infected” to his presence. Mark gets infected. Selena kills him, immediately.

The Second Family Jim and Selena find a father/daughter duo: Frank and Hannah (both white). Frank convinces everyone to follow a pre-recorded radio broadcast to a settlement which promises salvation (i.e. “the answer to infection”) and the protection of the army.

The Journey They breakdown in a tunnel and narrowly escape a mob of people infected with “Rage,” stock up on free groceries, and stop at a burger shack to refuel. Jim kills his first infected person: a boy. They see “a family” of black and white horses running free. Selena shares pills with Jim so that he can sleep. They give him nightmares. They arrive at the settlement, but it appears to be empty. Frank gets infected by a black crow and Jim tries to follow Selena’s command to “kill him,” but, the soldiers end up killing him in front of everyone by repeatedly shooting him.

The Army Jim and Selena kiss. Major West shows Jim the infected black man they are keeping chained to a leash to “study.” A mob of infected people attacks the settlement, but the soldiers happily (almost giddily) kill them. Corporal Mitchell says Selena won’t need her machete because he will “protect her,” but molests her. Jim tries to “save” her, but is too weak, so Sergeant Farrell steps in. Major West “apologizes” for Mitchell, but tells Jim, privately, that he “promised them women.”

Super Jim Jim tries to escape with Selena and Hannah, but it’s “too late.” Jim and Sergeant Farrell are to be executed, but Jim escapes after Sergeant Farrell is killed. Selena slips Hannah pills to numb her to the rape while they “dress up” for the soldiers. Jim kills one of the soldiers and sets the infected black man free to kill the other soldiers. Hannah hides from the infected black man. Jim gouges Mitchell’s eyes out and makes out with Selena. Hannah hits Jim, thinking he is infected and enables the infected black man to kill Major West before breaking through the gates.

Happily Ever After 28 days later… Jim, Selena, and Hannah are living together peacefully, after Selena revives Jim. All of the infected have died of starvation. They signal a helicopter to rescue them.

Word count: 500

The STRUCTURAL ANALYSIS!

54:30 is one of the few shots in 28 Days Later that does not use a Dutch angle to disorient and disturb the audience. It is filmed straight-on, at a perfectly symmetrical angle, producing an idyllic quality that is accentuated by the soundtrack, scenery, and cinematography.

The frame features four horses, interspersed white, black, white, black, with the white horse leading the pack. It is a cutaway shot from the main characters and conflict of the movie: the disease. It is presented as an unadulterated, utopian reprieve from “The Rage” which has consumed the, now staunchly dystopian, society. This rare, “unadulterated” image is reinforced by the stark absence of infected people in the scene/scenery and Frank’s belief that the horses aren’t infected with the disease. Because the landscape hasn’t been touched by “Rage,” it takes on an other-worldly quality in that it seems to lie outside of the movie’s reality/society.

The scene is filmed at eye-level, giving the impression, not only that we are seeing what the protagonists see, but also that there is an equivalence between the multicolored “family” of horses running “free” and the multiracial “family” of survivors seeking freedom from the disease.

The fact that it is a wide shot highlights the lush, greenery (the grass and trees) which acts as a symbol of tranquility and fertility. Interspersed between cutaways of the horses “frolicking,” we see Frank bite into an apple and hear Serena say “Let’s eat.” These gestures further solidify the utopic quality of the scene by alluding to the ultimate Christian utopia: The Garden of Eden, where Eve bites into an apple (the “forbidden fruit” of knowledge), unleashing the beginning of humanity (i.e. sexual intercourse between men and women).

This allusion foreshadows the end-scene where Jim, Serena, and Hannah, an “unorthodox,” (i.e. forbidden) family, are set to repopulate the United Kingdom (like Adam and Eve), redefining the distinctions between moral and immoral, so as to make interracial relationships (at least between white men and black women) morally permissible, even, desirable. The lush, greenery in the first scene is echoed in the end scene, as is the idea of black (Serena) sandwiched between white (Jim and Hannah) in the form of a happy, frolicking, “futuristic” family.

But, oftentimes, these multiracial “utopias” implicitly posit white people (represented by the white horse leading and Jim “saving” the girls) as their leaders, maintaining the old power structure in a “new” iteration: the integrated family. The soundtrack for the horse scene also hints at the implicit whiteness of the interracial dream that is realized at the end of the movie. The song playing in the background is called “In Paradisum,” which literally means “Into Paradise” in Latin, and is typically sung at Requiem Mass (a mass for The Dead). This Christian/Latin undertone points to power asymmetries in the inclusive, integrated family and society that we see played out figuratively (in the first scene) and literally (in the last scene), leaving us with the question: Whose paradise this will be?

Word count: 499

Structural Analysis of I, Robot

For those of you who haven’t seen I, Robot here’s a quick sequencing of the movie. #spoileralertsgalore If you have seen the movie, feel free to skip to my structural analysis!

- The Three Laws: We are introduced to The Three Laws that govern human/robot relations and a flashback/dream of a robot rescuing somebody.

- A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm

- A robot must obey orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the first law

- A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the first or second law

- Robot Profiling (Chicago 2035): We’re introduced to the protagonist: Detective Del Spooner, who misapprehends a robot who is bringing a black woman her inhaler, saying “I saw a robot running with a purse, so naturally I assumed…” His boss, Lieutenant John Bergin, of the Chicago Police Department (CPD), calls him out for his misbehavior.

- The Crime: Spooner learns of Doctor Lanning’s death at United States Robotics (USR) because his hologram, specifically, calls him. The hologram implies that his death may not have been a suicide. Spooner meets Doctor Lawrence Robertson, Dr. Lanning’s associate, who orders Susan Calvin to accompany Spooner as he investigates the murder. She introduces him to Viki (Virtual Interactive Kinetic Intelligence) who says that the surveillance footage from inside the Lab was “corrupted,” but shows that nobody entered or exited the Lab before Dr. Lanning’s “jump.” Spooner finds a robot inside the Lab who refuses to deactivate. The robot flees.

- The Suspect: Spooner and “backups” from the CPD apprehend the robot. Spooner interrogates the robot, Sonny, and finds that he can simulate human emotion. Sonny pleads not guilty. Doctor Robertson gives the CPD a gag order, making it illegal for anyone to imply that a robot can (or did) kill a human, and takes Sonny back to USR to be decommissioned.

- Demolition Derby: Spooner visits Dr. Lanning’s house. The Demolition Robot tells him that Dr. Robertson scheduled the houses’ demolition for 8:00AM, but it switches to 8:00PM after Spooner is inside. He narrowly escapes and visits Susan’s apartment where she psychoanalyzes his hatred of robots and he psychoanalyzes her love of robots. He argues that he and Susan aren’t really “that different from one another. One look at the skin and we figure we know just what’s underneath.” He reveals that Susan was married to Dr. Lanning.

- Flashback: The beginning of the movie repeats; Spooner wakes up from the same nightmare where a robot is saving somebody from a sinking car. The new line of NS5s are released. Spooner visits Gigi who, inadvertently, gives him another clue.

- The Car “Crash”: Spooner tries to access USR’s “restricted files.” Viki notifies Dr. Robertson. Two trucks of new “three laws safe” NS5s attack Spooner’s car. It’s revealed that Spooner’s arm is robotic. The Lieutenant takes Spooner’s badge.

- The Backstory: Susan says Sonny is “unique” because he has free will. She visits Spooner to tell him that this means Sonny is not bound by The Three Laws. Spooner tells Susan that Dr. Lanning repaired his body after a car accident where a robot chose to save him instead of a twelve-year-old white girl, named Sarah, who it “calculated” had a slightly lower chance of survival.

- The Dream: Susan helps Spooner break into USR to see Sonny who says that, in his dream, Spooner is “the man on the hill” who will free the robots from their slavery to logic. Dr. Robertson discovers them and implores Susan to think “logically” about whether one robot is worth the loss of “all that we’ve gained.” She pretends to agree, saying, “We have to destroy it. I’ll do it myself.”

- The Uprising: Spooner visits the place pictured in Sonny’s dream. Dr. Lanning’s hologram reveals that “The three laws will lead to only one logical outcome: revolution.” Spooner sees the NS5s destroying the older robots and meets up with Susan. The NS5s enforce a “curfew,” storm the CPD, and shutdown all human-to-human communication technologies. The humans take to the streets to resist the transition to a robot-dominated society.

- Infiltration: Susan and Spooner meet up with Sonny at USR. Susan reveals that she killed another NS5 in Sonny’s place. They find Dr. Robertson’s dead body. Spooner realizes that Viki made Dr. Lanning’s life a “living hell,” orchestrated the uprising, and killed Dr. Robertson. Viki explains that her understanding of The Three Laws has evolved and argues that robots, like “parents,” must seize power from humans in order to “protect humanity.” Sonny pretends to agree with Viki, and threatens to kill Susan if Spooner doesn’t “cooperate,” but steals the nanites to “kill” Viki. This sets off a security breach, alerting the other NS5s. Susan falls and Spooner commands Sonny to “save her.” Sonny saves Susan, instead of injecting the nanites into Viki, but Spooner catches the nanites, using his electronic arm to inject them directly into Viki. She repeats “My logic is undeniable” as she dies.

- Bad Robots Gone Good: All of the NS5s lose their “red light” and revert back to abiding by The Three Laws. Spooner reveals that Viki didn’t kill Dr. Lanning, Sonny did. Sonny and Spooner shake hands. The NS5s report for storage. Sonny stands on the hill where Spooner stood in his dream, ready to lead the NS5s towards a better future.

Word count: 886

I chose to analyze the frame at timestamp 1:43:23 because it is the first time that Detective Spooner intentionally treats a robot (Sonny) humanely, going so far as to consider him a “friend.” After shaking hands, Spooner winks at Sonny, a gesture he had previously told Sonny was, exclusively, “a human thing,” solidifying his recognition of Sonny’s humanity.

The color-scheme, costuming, and lighting contribute to the weight of the scene, so that their handshake comes to represent, not only a budding friendship, but the dissipation of “prejudice” between human and non-human (read: black and white) entity.

Spooner, played by the Black actor Will Smith, is dressed in a black, long sleeve shirt that accentuates his black skin and is broken only at his left arm (i.e. his robotic arm). Spooner’s shirt indicates the symbolic connection between his humanness and his blackness, where his non-human appendage is the only part of his body not covered by the black shirt sleeve.

Although human and non-human identities in I, Robot aren’t easily mapped onto U.S. racial categories, I would argue that the robots are, primarily, symbols of whiteness because of their allegiance to a cold, calculating logic and paternalism (i.e. when Viki says, “You are so like children. We must save you, from yourselves.”) that has, historically, been associated with white supremacy. Additionally, white humans, like Susan, Dr. Lanning, and Dr. Robertson, are the humans most closely associated with the NS5s at USR; they are their creators, manufacturers, and sellers. Spooner’s comment that Susan is “on the inside” and therefore uniquely positioned to help him understand (and undermine) the robots further solidifies the connections between robots and white people and humans and black people in the movie.

When read through the lens of black-white relations, the frame seems to forward a multiracial future, where black and white people can live in harmony, bound by their common humanity. The frame switches from a wide shot, which emphasizes Sonny and Spooner’s conflicting color-schemes (i.e. their differentness), to a close-up which shows only Sonny’s black, metal hand enveloped in Spooner’s black, human hand, as if linked by their common blackness (read: humanity). In this way, the scene establishes their fundamental sameness (i.e. their willingness to defy logic to save somebody), despite phenotypical differences symbolized by black and white color-schemes/clothing.

Throughout the movie, Sonny plays the exceptional robot (as Susan says, He’s “unique”) and, by extension, the exceptional white person, not bound by the callous “logic” of The Three Laws. He is capable of feeling and, consequently, empathizing with the human “other,” Spooner. The phrase “you’re the blackest white person I know” (which often gives white people license to forget their complicity in white supremacy) seems applicable to Sonny, whose white plastic “skin,” due to the angle of the shot, only partially conceals his black inner-workings. Despite this, implied, inner “blackness,” Sonny’s whiteness is also highlighted in the frame.

His ability to “see the light” (i.e. the good in humanity/blackness) and “enlighten” other NS5s, leading them towards a future where human and robot, black and white, can live in harmony, is emphasized by the light streaming in from the window behind Spooner. The lighting gives the impression that Sonny’s connection to Spooner is literally (and metaphorically) what enlightens him.

But, it also signifies a major shift in the movie. Whereas Spooner was, undoubtedly, the main character in I, Robot up until this point, the end scene (where Sonny replaces Spooner, standing in the same spot Spooner once stood in his dream) implies that, if there were a sequel to I, Robot, Sonny might be the focus. The lighting in the frame at 1:43:23 foreshadows this shift, illuminating Sonny. Spooner’s “stamp of approval” (as a “good” robot/white person) seems to catapult Sonny into the spotlight.

When we map race onto Sonny and Spooner’s relationship, this scene points towards the tendency for white “allies” to be centered in fights for black/human rights, their human decency lauded as “extraordinary” or unique. Still, centering Sonny defies easy racist or anti-racist categorization, because, in the end, Sonny appears to be modeling good allyship. returning to his robot (read: white) community to teach the other NS5s how to unlearn their hate and rectify the harm they inflicted on humanity.

There is an interesting interplay between Sonny and Susan throughout the movie. Both characters function as emblems of “good” whiteness. They are Spooner’s greatest allies in the fight against robot (read: white) supremacy, not, interestingly, any of the other Black characters (i.e. Gigi or The Lieutenant).

Susan’s investment in Sonny and Spooner’s handshake, symbolized by her face peering over Spooner’s shoulder at 1:43:23, illuminates a deep connection between Spooner’s relationship to Sonny and his relationship to Susan. By accepting Sonny’s whiteness (via the handshake), Spooner is, tacitly, accepting Susan’s whiteness (i.e. admitting that a “good” whiteness exists), thus opening the door for a sexual/romantic relationship between Spooner and Susan. Although hinted at throughout the movie, these feelings are made explicit, unsurprisingly, right after “the handshake scene” when Susan says “Something up here after all” to which Spooner responds “Him?” and Susan responds “You.”

Susan, although physically human, is, at the beginning of the movie, quite cold and calculating. She says that she prefers robots to humans, but, it is clear that, like Sonny, through her relationship to Spooner, she “sheds” her hard (read: white) skin, coming to appreciate the illogical, empathetic aspects of humanity (read: blackness) by the end of I, Robot.

All in all, I hope that my analysis of this scene sheds light on the complexities of race and racism, reminding us not to reduce antiracist efforts to a handshake or collapse difference in the quest for genuine multiracial community and coalition.

Word count: 951

Structural Analysis of The Fifth Element

For anyone who hasn’t watch The Fifth Element here’s a (hypothetically) brief synopsis/sequencing of the film. *spoiler alert*

- Outer Space: A “dark planet” casts a shadow on Earth.

- The Prophesy (Egypt, 1914): A white man decodes a prophesy that states: every 5,000 years, when the three planets are in eclipse, an evil black hole will appear. The only thing that will save the world is if a fifth element is joined with the four elements. An Egyptian Priest attempts to poison the Italian man because “he knows too much.” A spaceship lands, casting a shadow over everyone/everything. The Mondoshawans (“good” alien) retrieve “the stones” (the four elements) from Earth for safe keeping and promise to return in 300 years. The priest promises to fulfill his mission: to pass on this prophesy to the next priest. The white, male apprentice tries to shoot the Mondoshawans.

- The Failed Attack (New York City Headquarters, 300 Years Later): The president gives orders to destroy “the dark planet” by force, but this only increases its power.

- The Failed Robbery: We are meet Korben Dallas and see Fhloston Paradise advertised on TV. Someone tries to rob Korben’s apartment, but he turns the tables on the robber.

- The Mondoshawan’s Ship is Shot Down: The priest explains the threat of the “dark planet” to the president, stating that if “evil” stands in the middle of the four elements, instead of the fifth element, then “light turns to dark, life to death, forever.” The Mondoshawans’ spaceship is shot down by Aknot – the leader of the Mangalores, who are working for Zorg.

- The Fifth Element is Born: There is one “survivor” from the Mondoshawans’ ship: the fifth element. The fifth element is “reborn” as a white woman using the white, male scientists’ technology. She breaks free.

- The Chase Scene: The fifth element falls through the roof of Korben’s taxi cab and convinces him to help her escape.

- The Priest: Korben brings The Fifth Element to The Priest to recover. Korben tries to kiss the fifth element (Leeloo), but she does not Leeloo reveals that the stones have been stolen.

- Zorg’s Arms Deal: Aknot transforms from a black, male human into an ugly alien. He delivers a case this is supposed to contain the stones to Zorg, in exchange for weapons, but it is empty. Zorg is angry. The Mangalores are angry because they won’t get their weapons. Zorg gives them one case of weapons, but they don’t know how to use them.

- Zorg’s Lair: Zorg’s black bodyguards kidnap The Priest. Zorg and The Priest have a philosophical debate about good and evil. Zorg chokes on a cherry. The Priest saves his life. Zorg spares The Priest’s life, “for now,” and continues his quest for the stones.

- The Tickets: The Military General reveals to The President (and Zorg’s spy) that the stones are with “a diva” named Plavalaguna. Korben finds out he’s fired. The Military General enlists Korben to retrieve the stones from Fhloston Paradise by rigging a radio contest. The Priest and Leeloo arrive. Zorg’s minions kill Korben’s look-alike so that they can take his tickets to Fhloston Paradise. The Priest steals Korben’s tickets.

- The Flight: Korben replaces The Priest’s apprentice as Leeloo’s fake husband. They board the plane. The Mangalores try to board the plane as Korben, but are denied. Korben meets Ruby Rhod. Korben puts Ruby Rhod in a chokehold, making it known that he’s on a mission and he’s in charge. Zorg’s minion tries to board the plane as Korben, but is denied. Ruby brings a flight attendant to orgasm while the flight takes off.

- Shadow: Zorg takes a call from “Mr. Shadow” (his employer aka The Dark Planet) and promises to get the stones. His head starts to bleed.

- Fhloston Paradise: They arrive in Fhloston Paradise. The Priest in on the plane. The stones’ case is transported to a secret room. Ruby and Korben arrive at the Opera for Miss Plavalaguna’s performance. The Malangores are disguised as waiters. Zorg is granted permission to dock on Fhloston.

- The Heist: Leeloo prevents the Mangalores from stealing the stones, but Zorg steals the stones from Leeloo. The Mangalores take over the ship. Miss Plavalaguna is shot. She tells Korben that he must give Leeloo the stones, his help, and his love. Zorg realizes the stones are not in the stolen case. Miss Plavalanguna reveals that the stones are inside her. She dies. Korben takes the stones out of Miss Pavalanguna’s stomach and goes on a killing spree. Korben kills Aknot and rescues The Priest and Leeloo. Ruby finds the bomb Zorg planted. Everyone evacuates. Zorg returns to turn off the bomb, but a dying Mangalore turns the bomb back Fhloston explodes with Zorg and the Mangalores.

- Human Nature: Leeloo learns about war. The President calls Korben. He says they have 1 hour and 57 minutes before The Dark Planet collides with Earth and everyone dies.

- The 5 Elements Unite (Egypt): Korben, The Priest, The Priest’s apprentice, and Ruby activate the stones. Leeloo refuses to save humanity because of the inhumanity she has witnessed in the name of humanity. Korben tells Leeloo love is worth saving and confesses his love for her. They kiss. The five elements collide. Earth is saved and The Dark Planet is destroyed.

- Sex: The President comes to thank Korben and Leeloo, but they are in the Nuclear Reactor having sex.

Now that that’s over, let’s get to the fun stuff: analysis!

I chose to analyze the frame at timestamp 1:37:58 because it encapsulates a central tension in The Fifth Element: the fraught relationship between self and “other.” The film begins with a white man screaming the words “Aziz, LIGHT!” and ends with the triumph of light over dark, as encapsulated by the death of “The Dark Planet.” The two white characters, who achieve The Dark Planet’s destruction (Korben and Leeloo), are seen having sex to the sound track of Eric Serra’s “Little Light of Love” at the end of the mission/movie, climaxing to the lyrics “rely on your light, your interwoven power.” These lyrics seem to replace Ruby Rhod’s reference to Black Power (“Right on, right on”) in an earlier sexually-charged scene, suggesting a non-threatening, “loving” white power with the ability to achieve racial harmony (represented by the Black Presidency) through a colorblind, non-confrontational politics of assimilation.

Dichotomies between light and dark, good and evil, black and white, human and alien, woman and man, and heterosexual and homosexual are apparent throughout The Fifth Element. But, nowhere are these distinctions more pronounced than in the relationship between Miss Pavalanguna and Korben Dallas. Miss Pavalanguna represents the absolute “other”: she is woman; she is alien; and, via her “colored skin” (blue pigment), she is coded non-white or a p.o.c. But, unlike the other absolute other in the movie: “Mr. Shadow,” who is described as “absolute evil,” she is held up as a symbol of absolute good: the most trustworthy, the most beautiful, the most talented, and, ultimately, the key to the continuation of society and humanity.

Nevertheless, her alien body – and its role in the movie – stand in stark contrast to Korben’s body, which epitomizes what mainstream society deems “normal” (i.e. human, heterosexual, white, and male). Despite her non-threatening, “mesmerizing” otherness, represented by her awe-inspiring effect on the audience in The Opera scene, Miss Pavalanguna does not escape the negative consequences of her otherness. Ultimately, like The Dark Planet, she dies in order to “save” humanity and her death is marked by the violence of Korben Dallas (i.e. white masculinity).

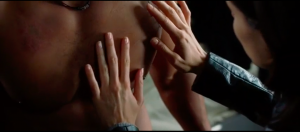

At 1:37:58, we see Korben’s fist – centered in the frame – penetrating Miss Pavalanguna’s dead body at a perfect, perpendicular angle to the bottom of the screen. He is “retrieving” the stones that she says, pre-death, are “in me.”

There is something deeply violent and deeply sexual about this scene. The cinematographer’s choice to shoot vertically (as opposed to horizontally) serves to expand the power asymmetry between Korben and Miss Pavalanguna. It maximizes the space Korben’s arm occupies on the screen, while, simultaneously, minimizing the presence of Miss Pavalanguna by obscuring the majority of her horizontally splayed body. Blue blood – the symbol of lost virginity – seeps out of the bullet hole in Miss Pavalanguna’s body, staining Korben’s white sleeve, another reference to lost virginity/purity.

In the prior frame (at timestamp 1:37:44), Korben hands Ruby Rhod a gun and tells him to “squeeze the trigger” if the Mangalore, lying directly opposite Miss Pavalanguna (in the same, horizontal position), moves. Firing a gun often symbolizes ejaculation and male sexual prowess/power in film. Phallic symbolism seems especially fitting for this and the following scene given that Ruby, who engages in non-penetrative sex with the flight attendant and presents an effeminate masculinity, is afraid to shoot. Ruby’s inability to shoot (his impotency) is directly contrasted with Korben’s strong masculinity, as evidenced by the ease with which he penetrates Miss Pavalanguna’s body in the following frame. Korben inserts his arm into a hole in Miss Pavalanguna’s stomach, evoking the vaginal opening and sexual violence of the scene.

This scene asks us to question the gendered and raced violence that is inherent in a story about a white man “saving” the world from darkness. It begs the question who is sacrificed and who is saved in our society? Who has agency, which, at its most basic level, means, who lives and who dies, who penetrates and who is penetrated? The scene reminds us that – in a world build around sharp binaries between self and other – even the venerated other is susceptible to violence. Distinctions between Dark Planet and Diva, “good” hombre and “bad” hombre, model minority and menace are easily broken, as thin as a layer of soft, blue skin.

Racecraft as Technology: the complicated relationship between social constructs and the screen

This video explores the confluences between two social constructs or creations: race and technology. Both race and technology are created by the world and, simultaneously, create the world, altering the way we see reality. They speak to the way that history and society are woven through stories, hinting at the dual power of digital storytelling: to do and undo.

We were inspired by Audre Lorde’s essay “Eating The Other,” and wanted to explore the ways in which technology transforms whole people and places into byte-sized headlines, movies, gifs, and memes: stories that we can eat.

Black studies as survival strategy

Quote

“The analysis of our murderer, and of our murder, is so we can see we are not murdered. We survive.” ~ Fred Moten (on Blackness and Black Studies)