Do we really care about the feminist struggles of the protagonists who disguise themselves as males to get an access to a male-dominated sphere? Often in movies and tv series, these female protagonists strive to refuse expected gender roles imposed upon them and prove themselves as professionals capable of achieving what the male characters do. Yet as viewers, at least for me, our central concern is not so much about their successful accomplishment in realm of professionalism but about the romance between a male and female character. We impatiently ask: so when is her future lover is going to find out that she is not a man? And it is a natural question to ask, since the tension that drives the plot is a romantic one, and confrontation of real life discrimination is given secondary importance in their depictions. It is fair to say that those media productions are in fact about love stories of the female and male character, who stays unbelievably oblivious until the very end despite the fact that the female protagonists usually have the stereotypical characteristics of traditional femininity–either very sassy outside the disguise or with traditional gender expectation of females–and those traits make the disguise unconvincing.

This golden cliche also applies for the female protagonist in She’s the Man, who dresses up as her twin brother to join the boys’ soccer team in his school. In the end, she is accepted as a member of the soccer team as a female and beat her ex-boyfriend in a rival soccer team. The festive scene in the end that shows her victory almost reminds one of a carnival scene: the loud crowd cheers at the players, people take their clothes off, and the comic depiction of the defeat of the traditional male power celebrates the inversion of hierarchy. As shown in the movie description, this scene indeed seems to show that “girls can do anything guys can do.” But it is not any girl who is accepted as a member of the domain allowed only for males is not any girl: it is the hot girl that is shown on the poster for She’s the Man, the one that falls in typical female gender description.

I am saying we should be bothered by such association established in the movie, and take this cheesy rom-com as more than a “harmless fun for the 12 year olds” as noted by one critic. The reason is that the ideas linked with different aspects of gender throughout the movie tells us a very different story about the ideal world suggested by the movie, and this feigned utopia is just a different way of describing the reality the female protagonist was trying to escape from.

Ideas and imageries this movie uses to frame and construct male and female genders are glaringly simple. The female protagonist, Viola, chooses to play soccer instead of becoming a debutante as constantly insisted by her mother. In Viola’s nightmare, she is wearing a heavy dress with flares which restricts her movements and make her embarrass herself in the soccer field (00:27:18). The dresses that police one’s body represent the traditional role of female, and Viola’s choice to be a female soccer player as a way of freely using her body is an escape from such gender expectation. If they are to refuse the dresses and be soccer players, what would be the new outfit that suits them? There is only scene from the entire movie that shows girls’ soccer team having a match, and they are all wearing bikinis (00:00:50). So an alternative to a dress is not a soccer uniform–but a bikini. The scene that celebrates liberation of these girls focus on their breasts, legs, and the curves of their half-naked bodies in close-up freeze frames. This opening scene of the movie sets a new definition of female gender: if they are not going to be ladies in pretty dress, they will be hot girls in bikinis seducing male audience. A coincidence or not, the lyrics of the background music of the scene, No Sleep Tonight by the Faders tell us what messages these girls may be sending to their male spectators.

“You want me

You want me all the time

…

Baby I’m what’s on your mind

You can’t stop this feeling”

These lyrics once again reinforce the mental connection between females and their sexual appeal. So the girls who want to escape from their traditional gender frame have to redefine themselves in terms of their physical appeals.

Viola’s transformation from female to male focuses on hiding physical features and process that defines females in this movie–her hair, breasts, and tampons. Then she learns to walk, talk, and spit like a man. (00:13:31) This juxtaposed contrast piece together for the audience that physical traits define a woman, and actions define a man. These differences become more apparent in the male-talk and woman-talk in number of occasions. When her ex-boyfriend Viola compliments her that she has become better at soccer, Viola responds that he has gotten better at kissing and that she has taught him well (00:02:57); when the two argue, the ex-boyfriend is the one who says “End of discussion!”, to which Viola responds, “Then, end of relationship.” (00:05:31). Because physical skills are alien to female gender, Viola and her soccer teammates are described as amateurs throughout the movie. In fact, when Viola tries out for a boy’s team disguised as her twin brother, she finds out that she is in fact not as good as male soccer players (00:18:35). Indeed, to break the limitations of her gender and be elevated as an amateur to a professional, Viola has to get help from her future boyfriend Duke–a name that connotes social status. Again, a simple binary distinction between the two genders arise from their interactions: women provide sexual pleasure to men, who in return can teach them skills and allow their entrance into realm of professionalism.

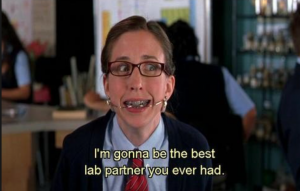

Other characters, Eunice and Monique, who do not fall in such description of femininity function as jesters whose appearance and behaviors induce laughters from the audience. Eunice, a socially awkward character who wears glasses and braces is the best representation of stereotypes about smart girls. When she becomes the lab partner with Duke and tells him that “I am gonna be the best lab partner you’ve ever had”(00:34:18) as she looks at Duke in an excessively seductive way. Her expression of sexual desire looks awkward, as if intelligence and sexual appeals are two incompatible characteristics that appear comical and elicit laughter. But what exactly are such scenes asking us to laugh at? Is it not encouraging us to mock the connection between a female with intelligence and their unpleasant femininity that, as confessed by one online commentator, even causes the feeling of “disgust”? Through the gender dynamic presented in She’s the Man, females with skills are unattractive, if not repulsive.

Monique, a stereotypical blonde girl who is considered “hot” among male characters in the movie, is on the other side of the spectrum and still the femininity she represents is also not desirable from the movie’s perspective. She is confident enough to reject a guy and say, “girls with asses like mine do not talk to guys with face like yours” (00:31:59). But Monique is rejected by Viola, who Monique mistakes for her twin brother Sebastian and makes fun of her in front of the crowd by calling her ugly. The defeat of the hot girl who is attractive yet unwilling to be their girlfriend generates feeling of catharsis among the male characters, who describe Viola as their role model. A member of female gender in the movie falls in one of the three categories: she is hot and spiteful, she is smart and repulsive, or she is attractive enough but also needs help from men. And I do not have to tell you which of the three types represents an authentic female the viewers and crowd cheer at in the end of the movie.

But Viola herself is subject to laughter before she reveals her true gender–that is, before she clarifies that her feeling for Duke is not homosexual. Physical contacts between Duke and Viola when she is pretending to be Sebastian always end in Duke’s awkward rejection or exaggerated shuddering. Even Viola makes it clear that she has no sympathy toward queer love. Meyer in her paper notes that Viola’s “persistent attempt to avoid intimate moments with Olivia”, a very attractive girl who mistakes Viola for a guy and falls in love, in fact “underlines the devalued and humoristic aspects of same-sex desire.” Homosexuality in the movie is something that can be readily used as a bad pun in a scene where Viola’s mom asks to the debutantes, “Now, who is ready to come out?” (1:03:49). She is the Man, a story that revolves around only two authentic genders, invites the viewers not only to laugh at queerness but also to root for Viola to reveal her heterosexual love for Duke. Viola’s choice to dress herself as a man lost its initial significance as a means to resist the discrimination in her life, and it is no more than an obstacle she has to overcome to be loved by Duke, a new life-goal that quickly replaces her original goal. Duke’s response to Viola’s confession of love summarizes how the movie views same-sex love in one phrase: “That’s just weird.” (1:27:10) Viola has to assert her femininity which is defined by her breast and her desire for a male. (Meyer, 2011). Now there indeed is no hindrance to their love, and Duke gladly confesses that “everything would’ve been so much easier if you [Viola] stayed as a girl” (1:38:14).

The carnivalesque scene in the end of the movie does appear to cheers Viola’s victory against her opponents and her successful achievement of the initial goal in wild festivity. It pretends to be a utopia where traditional hierarchy and rules are thrown out of windows. When Viola confesses that she is in fact a girl who pretended to be Sebastian to be a part of the team, her soccer coach explicitly claims that “we do not discriminate people based on gender” and tears up the soccer manual book (1:29:45). After a direct negation of the traditional rules, Viola runs as the first wing player while the American flag symbolically flashes in the background. However, even in this ideal world that claims to embody American dream, females are still associated with unprofessionalism. The soccer coach calls his players a “bunch of girls” as they lose focus of the game and end up fighting with one another(1:26:32). In this world, Viola confesses her feelings for Duke after the removal of an obstacle–her potential queerness–and succeeds in dating Duke, yet another traditional masculine figure who is described to be a “sensitive guy” with feelings but is quick to be seduced by sexual appeals of Olivia and Viola. In the ending scene, Viola is happy to be the girl accompanied by a male to her debutante party in her elegance dress, the traditional role of a female she was so desperate to escape from.

The utopia this movie suggests in the end celebrates the firm re-establishment of traditional orthodox power. In the end, just like many other bad rom-coms, love is an explanation to everything. But it has to be a heterosexual love between an attractive girl who is only made happy by a guy who teaches her how to be a professional. Her feminist goal? Again, coincidence or not, the closing song Move Along by The All American Rejects provides you with an answer:

“Move along, move along like I know you do

And even when your hope is gone

Move along, move along just to make it through”

Yes, move along, even if there still may be discriminations, because us women will be saved by our fellow men “as long as they conform to the codes of femininity within the matrix of heterosexual relationships (Butler, 1990).”

Revised by Juna Khang

Works cited

Butler, Judith (1990). Gender Trouble. New York: Routledge Falmer.

Fickman, Andy. About the Movie, ITunes Preview, web.

Meyer, Elizabeth (2011). “She’s the Man”: Deconstructing the Gender and Sexuality Curriculum at “Hollywood High”. Counterpoints, Vol.392.