“Milton’s Paradise Lost: Author and Book as Concomitant Experience”

By Victoria Wang

Prompt: 8. When we read a novel or poem, the author is, in a sense, part of the fiction. The author, this is to say, possesses an image or reputation. It doesn’t matter whether this image is correct or not; it’s a kind of literary effect alongside a given novel’s other literary effects. Readers bring to many books things they at least think they know about their authors, and this author-image will frame how they read in ways that we as literary critics and historians shouldn’t just ignore.

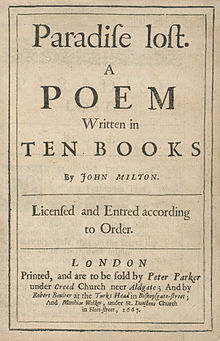

The author is not dead. More precisely, the author as sole creator of a text’s truth has diminished, but the author as image and description is well and alive (Foucault 121). In his seminal essay “The Death of the Author,” Barthes states, “The Author, when believed in, is always conceived of as the past of his own book; book and author stand automatically on a single line divided into a before and an after” (145). However, the Author need not be an anchoring antecedent on his or her book. One can believe in the Author yet conceive of book and author as existing simultaneously. If we view the Author as more of an author-persona than an author-person, an analysis incorporating the author does not purport to capture some unassailable, singular reality about the historical figure’s intentions or psychology (Walker). Rather, the analysis takes into account the fact that the lives of authors are often public knowledge in the same way their books are. It acknowledges that many readers have at least a rudimentary conception of the author (at the very least, a proper name) that will frame how they read the book. Thus, the author does not come before the book; most often, he or she comes attached with the book.

Textual purists contend that knowledge of whether a poem was written by Milton or Dryden should not affect evaluation of that poem. That is to say, the poem should stand apart from whoever’s hand penned it. This high-minded conception of a text as “detached from the author at birth” sounds rational in theory, but what should happen is often not what happens in practice (Wimsatt and Beardsley 1376). Unless I cover my eyes such that I avoid ever glimpsing a proper name in a book, I know that I am reading Paradise Lost by Milton and not a Paradise Lost by Dryden or a Paradise Lost that miraculously manifested without a creator. Insisting that I feign ignorance about the author’s identity while reading is like asking Eve to go about her days as if she hadn’t already consumed the fruit from the Tree of Knowledge – regressive, inefficient, and futile. There is no cure for cognizance; knowledge is not so easily erased or suppressed. Readers could attempt to keep themselves in check whenever they stray too far from what is strictly within the text, but surely there are better uses of our time than disentangling perceptions of the text from perceptions of the author.

If we grant that enacting curative measures around authorial awareness is difficult if not impossible, then we turn to the possibility of preventive methods instead. For instance, one could advise readers to limit their exposure to authorial context. We already know that Milton wrote Paradise Lost, but perhaps we have not yet learned about Milton’s other writings or about his biography. In order to appreciate the text in isolation (or as close to isolation as we can reasonably achieve), we should refrain from seeking out any additional information regarding the author. Yet something about this recommendation feels antithetical to the scholarly spirit. I am hard-pressed to consider the perpetuation of ignorance liberating. A modification of this preventative strategy could involve avoiding authorial context up until we have separately formed our impressions of the text. This process effectively forces the author to come after the text instead of before the text. To test this “temporary ignorance” strategy in action, I conducted a pre-author and post-author analysis of the first 26 lines of Paradise Lost:

Of Mans First Disobedience, and the Fruit

Of that Forbidden Tree, whose mortal tast

Brought Death into the World, and all our woe,

With loss of EDEN, till one greater Man

Restore us, and regain the blissful Seat,

Sing Heav’nly Muse, that on the secret top

Of OREB, or of SINAI, didst inspire

That Shepherd, who first taught the chosen Seed,

In the Beginning how the Heav’ns and Earth

Rose out of CHAOS: Or if SION Hill

Delight thee more, and SILOA’S Brook that flow’d

Fast by the Oracle of God; I thence

Invoke thy aid to my adventrous Song,

That with no middle flight intends to soar

Above th’ AONIAN Mount, while it pursues

Things unattempted yet in Prose or Rhime.

And chiefly Thou O Spirit, that dost prefer

Before all Temples th’ upright heart and pure,

Instruct me, for Thou know’st; Thou from the first

Wast present, and with mighty wings outspread

Dove-like satst brooding on the vast Abyss

And mad’st it pregnant: What in me is dark

Illumine, what is low raise and support;

That to the highth of this great Argument

I may assert th’ Eternal Providence,

And justifie the wayes of God to men.

I relied on the text and only the text for the first “author-less” portion of my analysis. One thing I noticed in my textual analysis is that Paradise Lost makes multiple allusions to Greek classics. Its invocation “Sing, Heav’nly Muse” is clearly reminiscent of Homer’s Odyssey (“Sing to me of the man, Muse, the man of twists and turns”), and the poem also refers to the Aonian Mount, a mountain that was important to the Muses in Greek mythology. Thus, Milton frames Paradise Lost as an epic of Man. The plain meaning of the introduction is that Milton beseeches the Heavenly Muse, the Christian counterpart to pagan Greek Muses, for assistance in telling his story and upholding God. The reader may be tempted to conclude that Milton is subordinating himself to the Heavenly Muse. However, if we look at the specific diction in the poem, we draw a much different conclusion. Upon closer examination, Milton draws parallels between himself, his poem, and the Heavenly Muse. His adventurous song intends to soar “Above th’ Aonian Mount, while it pursues/ Things unattempted yet in Prose or Rhime” (15-16). By saying that his song intends to soar over this mountain, Milton suggests that it both overlooks the Greek muses and classics, i.e. it recognizes them and uses them as a landmark or measuring stick, and ultimately hopes to surpass them. This action of soaring imbues the adventurous song with avian characteristics. Later, Milton says that the Heavenly Muse should instruct him with its knowledge, since “Thou from the first/Wast present, and with mighty wings outspread/Dove-like satst brooding” (19-21). The Heavenly Muse is described as possessing wings and being “dove-like,” a direct continuation of the bird-like imagery used to characterize Milton’s writing. Finally, we switch subjects to Milton himself. He writes, “That to the highth of this great Argument/I [emphasis added] may assert Eternal Providence,/And justifie the wayes of God to men” (24-26). Now Milton is the one at great heights asserting his persuasive power; he has also become bird or dove-like. Read in this way, the author is his work is the omnipotent figure from whom he seeks inspiration and knowledge.

For the second part of this “temporary ignorance” exercise, I reread Paradise Lost after learning about Milton’s biography and religious beliefs. In my research, I discovered that Milton read classical epics such as Homer’s Odyssey and Iliad during his school days and envisioned writing a nationalist English epic himself. While he enjoyed and respected Greek classics, he “did not think the Greek classics the most important branch of learning or the best of all literature. Ethics was the one, the Bible the other” (MacKellar and Merritt 209). Previously, I interpreted the lines “Invoke thy aid to my adventrous Song,/That with no middle flight intends to soar/Above th’ Aonian Mount,” (13-15) as suggestive of Milton’s desire to contribute and perhaps even surpass the lineage of epics that came before Paradise Lost. The biographical data supports my interpretation that while Milton appreciated the Greek classics, he believed that he could do better in subject material, that is, the Bible. But while this particular tidbit of information corroborates my “author-less” analysis, other pieces of authorial context may invite greater uncertainty. For example, secondary sources posit that Milton viewed God as an author figure and Christians as readers (Stallard xvi.). I noted that Milton draws parallels between himself as author, the text, and the inspiration or guidance of the Heavenly Spirit. But if God is in fact the original author, then it seems Milton is comparing himself and God, which comes off as a peculiarly ego-driven, even blasphemous act for such a fiercely devout Christian. In this scenario, permitting the author to enter literary criticism produces more questions than it resolves. The author’s biography does not have to serve as a shortcut for or substantiation of textual analysis; it can also disrupt previous readings of a text and incite us to take on different angles during interpretation. Far from “closing” the text as Barthes has accused, giving Paradise Lost an author actually “opens” it further.

Although this “temporary ignorance” strategy appears to make space for both text-based and author-based readings, I balk at the idea of enforcing an experimental procedure onto the act of reading. Delaying full comprehension may be a popular method in the sciences, as exemplified in double-blind experiments (keeping information about the test from the participant and researcher until after the trial outcome is known in order to eliminate unrecognized biases), but it is a restriction imposed on literary analysis precisely like that which anti-author critics are trying to avoid. As we have seen from my case study of Paradise Lost, the introduction of biographical context can generate new interpretations of a text. Furthermore, a basic level of author awareness is a literary effect inescapable to the point that I question why we feel the need to escape it in the first place. Knowing Milton’s religious beliefs affects how one reads Paradise Lost, but that would be the case with any type of prior knowledge or experience. Having read the Odyssey, or having lived in the U.S. as opposed to England, or having sympathy for rebellious figures – these are all biases that could affect how a reader interprets Paradise Lost. Nothing exists in uncorrupted isolation; reading a book is no exception. Awareness of the author is quality readers have in varying degrees, just as they may have different levels of exposures to Western canon or to general discourse surrounding the book. We should not treat author and book as source and output, nor should we force the author to come after the book through the methodology of sequential reading. Instead, we should think of author and book as literary experiences that occur simultaneously. Author and book cannot and should not be separated.

Sources

- Barthes, Roland. “The Death of the Author.” 1967.

- Foucault, Michel. “What is an Author?” 1969.

- MacKellar, Walter, and Merritt, Hughes. A Variorum Commentary of the Poems of John Milton: Paradise Regained. 1975.

- Milton, John. Paradise Lost. 1667.

- Stallard, Matthew. Paradise Lost: The Biblically Annotated Edition. 2011.

- Walker, Cheryl. “Persona Criticism and the Death of the Author.” Contesting the subject: essays in the postmodern theory and practice of biography and biographical criticism, edited by William H. Epstein. West Lafayette, Ind: Purdue University Press. 1991.

- Wimsatt, William K. and Beardsley, Monroe C. “The Intentional Fallacy.” 1946.