“Marvel’s ‘Luke Cage’ and the Trojan Horse of Fiction” by Victoria Wang

PROMPT

Philosophical and scholarly writing is often powerful, but is typically written only for already educated people. It teaches the already taught. Literature, by contrast, can convey serious thought, but it does so in generally accessible ways (and in a form that doesn’t feel like work). Poems and novels and plays are philosophy for the many.

NOTE: In this essay, I use a broad definition of literature that encompasses film and TV as well as written novels. I use the term “literature” interchangeably with “fiction” and “stories”. I refer to both written and non-written pieces as “texts” and those engaging with the texts as “readers” or “viewers” or the “audience.”

Stories are an exercise in empathy. In “Fiction: Simulation of Social Worlds,” Keith Oatley posits, “Fiction is the simulation of selves in interaction. People who read it improve their understanding of others.” A reader identifies with a character despite their differences; this empathetic identification even extends to a racial other. Psychology researcher Dan Johnson finds in his study “Changing Race Boundary Perception by Reading Narrative Fiction” that participants who read an account of a Muslim woman consequently exhibited lower categorical race bias towards Arabs. Although it is too early to conclude from this study that fiction can reduce racism, the potential for stories to affect their readers in the real world is certainly there. If we accept the far-reaching persuasive scope of fiction, then the question arises of how to harness this power for good.

Of the fall television premieres, Marvel and ABC’s Luke Cage is uniquely placed to inspire social action through storytelling. The protagonist of Luke Cage is a wrongfully convicted black man who gains impenetrable skin from a prison experiment. After escaping from jail, he attempts to keep a low profile but finds himself drawn into a conflict with Harlem crime cousins Cornell Stokes and Mariah Dillard. Luke must protect his neighborhood in the ensuing conflict between cops and criminals. Luke Cage tackles themes such as racial discrimination, gentrification, gun violence, and police brutality head on, and the creative minds behind the neo-Blaxploitation series have shown they are keenly aware of the real-world ramifications of fiction. Lead actress Simone Missick, who plays tough detective Misty Knight, says:

Black people have been traditionally disenfranchised and abused and misused in this country. […] All are things we know, but we haven’t really seen them talked about onscreen. It’s important because it gets a dialogue going. I don’t think this show is aiming to cure all these social ills, but it is opening up a dialogue […] The show’s ability to do that on a global scale is very powerful. (qtd. in Bastien)

While a show like Luke Cage cannot and does not attempt to single-handedly cure the social ills of the United States, Missick believes the show can at least start a conversation about these issues. She alludes to the capacity of popular media to spread messages to a global audience. Head of Marvel’s television division Jeph Loeb expresses a similar hope, “If we can get one person to watch the show and to think differently about what it is to be a hero in the present day, and what it is to be a black hero, then that’s a victory” (qtd. in Tanz). He explicitly declares an intent to sway viewers and takes for granted that a fictional TV show can do so. His statement also provides a clue as to where literature and fiction deviate from philosophical and scholarly writing. Before the creators of Luke Cage can get one person to think differently about the black hero, they need to “get one person to watch the show.” This prerequisite of capturing audience interest differentiates stories from more overtly didactic texts.

The cast and crew of Luke Cage understand that effecting real change through fictional means is a two-stage process. Mike Colter, the actor who plays the eponymous protagonist, notes that while Luke Cage may offer pointed social commentary, it is first and foremost “a Marvel TV show about superheroes” and needs the capacity to be enjoyed as such (qtd. in Friedlander). The show’s creator Cheo Hodari Coker explains:

And so with this show, you have the opportunity to kind of use it as a Trojan horse with which you can introduce a host of other issues besides it being a superhero story. […] It works on two different levels. It isn’t a polemic. And I really think that with this kind of show, you can do both. What I wanted to prove is that you can enjoy a superhero show and still be part of what’s happening in the world. (qtd. in Leon)

Luke Cage is simultaneously educational (the viewer becomes “part of what’s happening in the world”) and entertaining (the viewer simply enjoys a superhero show). In fact, entertainment serves as a vehicle to convey education to audiences. Coker portrays the show as a “Trojan horse,” a form of subterfuge that causes the target to invite his foe into a securely protected place. Once the viewer accepts Luke Cage as interesting enough to watch, he allows the “host of other issues” discussed inside the show access to his domain as well. The viewer expects an action-packed show about superheroes – which he receives! But he also receives a thoughtful exploration of black history and culture in Harlem. And if the show does this deftly enough, the viewer won’t even mind that he has been cajoled into learning a few things along the way.

The underlying assumption of this strategy is that people are cautious towards truths presented in lectures but are susceptible to truths wrapped in stories. Nobody walks into a story expecting truth; rather, they expect a beautiful lie. People appreciate artistry, the capacity of a work to create an appealing and convincing illusion. Going a step further, it can be said that people appreciate artifice – a term that originally referred to skillful human craft and later took on connotations of deceitful construction (Cronon, 488). Fiction embraces artifice more than any other human craft. However, audiences may not realize on just how many levels this subterfuge operates in fiction.

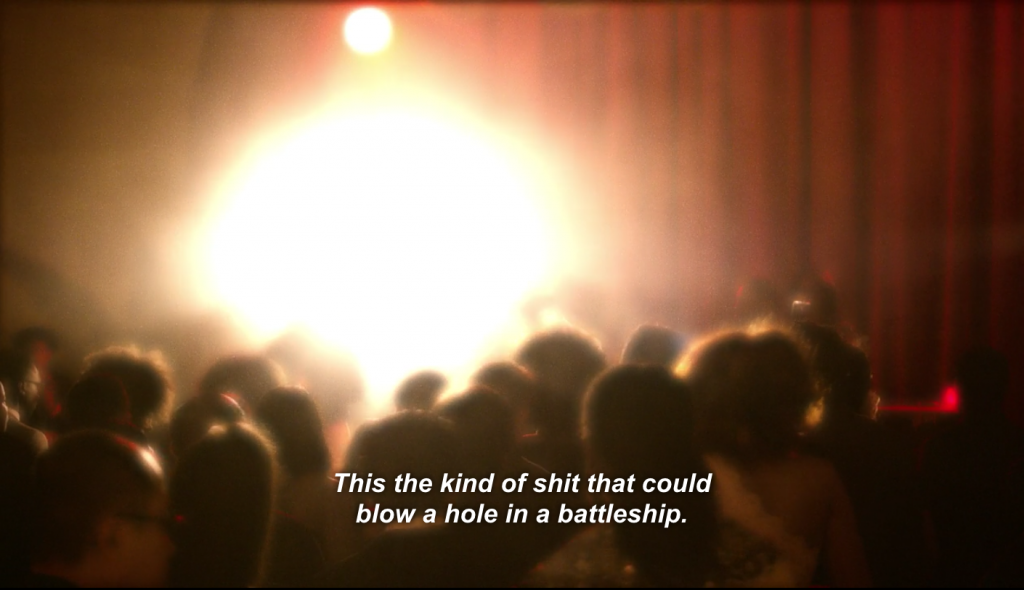

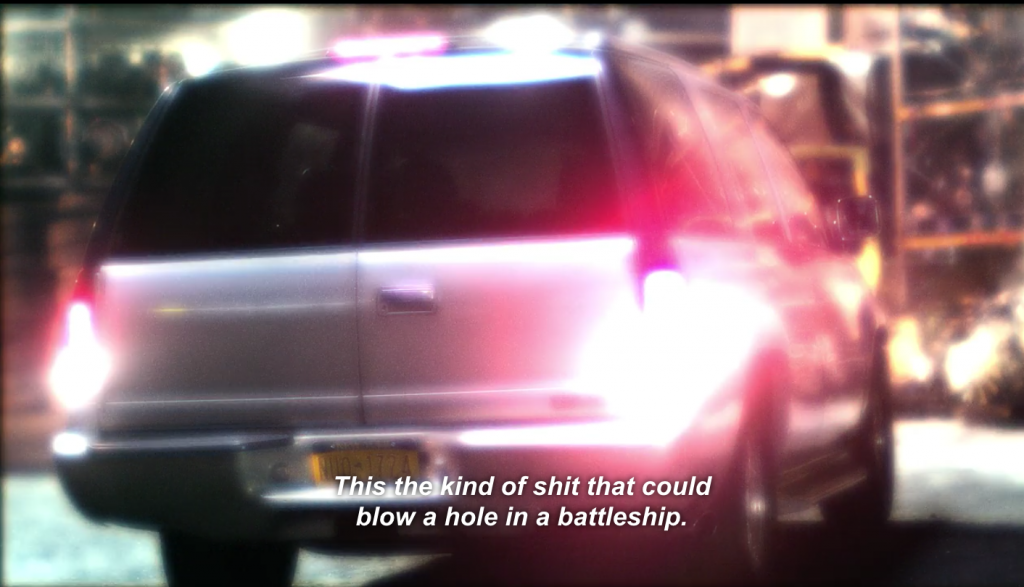

Deception within deception lays the groundwork for one of film’s greatest tenets: cinematic invisibility. Film uses a myriad of integrated techniques and concepts to connect the audience to the story while “deliberately concealing the means by which it does so” (Barsam 3). Even if a viewer doesn’t detect the precisely chosen color scheme or discern the purpose of a particular camera angle, he can still be affected on a subliminal level. The first episode of Luke Cage features a two-minute sequence that alternates between an illicit gun deal gone wrong at an abandoned junkyard and a soulful musical performance at the nightclub Harlem’s Paradise (36:50 to 34:55). Most viewers pick up on the dissonance of pairing gang violence with the ironically innocent song choice of “Angel.” Fewer viewers can unravel the combination of cinematic devices employed to evince this overall sense of juxtaposition. Cornell Stokes is known as the reputable nightclub owner of Harlem’s Paradise, but he also heads illegal drug and gun trading activity in the streets. As Stokes meets with a buyer on the balcony of Harlem’s Paradise, the club singer begins his performance. The stage lights brighten into the headlights of the car transporting the merchandise.

This self-conscious transition invites the viewer to compare the events of the two locations in the proceeding intercut sequence. It soon becomes clear that the two scenes are comparable. The fight scene at the junkyard is slowed to match the tempo of the performance at Harlem’s Paradise; gunshots ring out in the spaces when the singer pauses for breath or coincide with the drum beats in the song. We can also see that graphic and spatial relationships are maintained from shot to shot.

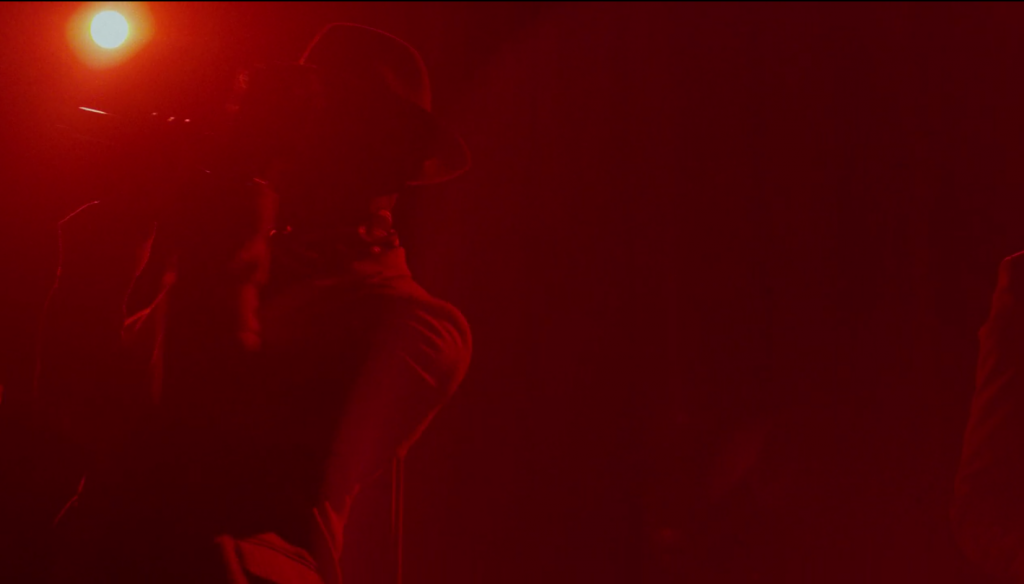

The visual composition of the frame featuring the gunman corresponds almost perfectly to the composition of the frame featuring the singer. The spotlight is located in the upper left-hand corner and the actor on the left side of the screen in both shots. However, the gunman and the singer face opposite directions, right and left respectively. Additionally, the color palette of the junkyard scene is blue, and the color palette of the Harlem’s Paradise scene is red: a complementary color scheme that implies conflict and contradiction.

The cumulative effect of these distinct techniques is to impress upon the viewer that violence and beauty are two sides of the same coin. Look, the show seems to be saying, look how beneath the glamorous veneer of Harlem’s Paradise lies a violent, crime-ridden underside, a Harlem’s Hell. But a viewer doesn’t require a background in film or literary analysis in order to receive this message. In fact, cinematic sleight of hand often produces a more seamless experience when it goes unnoticed — when the viewer has been completely taken in by the show. An eagle-eyed viewer is actually less likely to be moved by the story because he can expose the inner workings of its rhetorical devices and cinematic techniques. The perspicacious viewer has broken through the illusion of the illusion, and thus at least partially broken the hold of fictional trickery.

Yet fiction manages to pull off an even more impressive deception: the idea that it is somehow separate from reality. The viewer doesn’t think to gird himself against external influence when watching a superhero show the way he might when watching the news. Consequently, he is more vulnerable to the persuasion of fiction than to any philosophical teaching. It would be more accurate to say that fiction is a metaphor for reality, used as a Trojan horse to bypass the viewer’s inherent defense mechanisms around the real. Coker says of the superhero genre, “It’s much easier to talk about racism when you’re able to use mutants as a metaphor. People would much rather talk about Charles Xavier and Magneto than they would about Martin Luther King or Malcolm X” (qtd. in Moss). Fiction needs to be close enough to reality to stay relevant but far enough to maintain an aesthetic distance. Luke Cage can put the invincible black man in a bullet-torn hoodie as a nod to Trayvon Martin, but it can’t have a character give a ten-minute speech on racial profiling. The show must be careful not to jar the audience out of their impression that Luke Cage is a story, albeit a particularly pertinent one. This layer of obfuscation enables literature to impact the viewer without alienating him.

Sweet lies that mask the bitterness of truth, stories are all the more potent for their perceived disconnect from reality. The average viewer has not yet learned to be as wary of a superhero show as he is of a treatise on structural racism. Thus, fiction can change minds and incite action where sermons and lectures falter. A text can draw on any number of facts and statistics to thrust at its audience. 12,942 Americans were killed by guns in the year of 2015 (“Gun Violence”). One in six black men had been incarcerated as of 2001, and if the trend continues, one in three black males born today can expect to spend time in prison at some point in his life (“Criminal Justice”). On average, the probability of being black, unarmed, and shot by police is approximately 3.49 times the probability of being white, unarmed, and shot by police (Makarechi). That isn’t the tactic Luke Cage takes. Instead, the show gives us the wearied expression on Luke’s face as he is held at gunpoint by a young black gang member. It shows us the dehumanizing conditions of prison and the failings of the justice system through the lens of one man’s experiences. It tosses us an offhand, “Everyone has a gun, no one has a father.” Luke Cage is all the more persuasive for not conveying its message outright. The ability of stories to influence their audience without seeming like they are doing so is their most powerful asset. By pretending that it is apart from reality, fiction can change reality.

Sources

Barsam, Richard. “Looking at Movies: An Introduction to Film.” New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2013.

Bastien, Angelica Jade. “Luke Cage’s Breakout Star Simone Missick on Playing Misty Knight, the Politics of the Show, and Improv On Set.” Vulture. September 30, 2016. http://www.vulture.com/2016/09/luke-cage-simone-missick-misty-knight.html

“Criminal Justice Fact Sheet.” NAACP. 2016. http://www.naacp.org/criminal-justice-fact-sheet/

Cronon, William. Uncommon Ground: Rethinking the Human Place in Nature. New York: Norton & Company, 1996. Print.

Delistraty, Cody. “The Psychological Comforts of Storytelling.” November 2, 2014. The Atlantic. http://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2014/11/the-psychological-comforts-of-storytelling/381964/

Friedlander, Whitney. September 30, 2016. “Mike Colter Explains the One Word He Doesn’t Want Luke Cage to Say.” Esquire. http://www.esquire.com/entertainment/tv/q-and-a/a49109/luke-cage-mike-colter-interview/

Gørrild, M., Obialo, S. & Venema, N. “Gentrification and Displacement in Harlem: How the Harlem Community Lost Its Voice en Route to Progress.” Humanity in Action. 2008. http://www.humanityinaction.org/knowledgebase/79-gentrification-and-displacement-in-harlem-how-the-harlem-community-lost-its-voice-en-route-to-progress

“Gun Violence by the Numbers.” Everytown. December 2015. https://everytownresearch.org/gun-violence-by-the-numbers/

Johnson, Dan. “Changing Race Boundary Perception by Reading Narrative Fiction.” Basic and Applied Social Psychology. February 10, 2014. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01973533.2013.856791

Leon, Melissa. “‘Luke Cage’ Creator on Black Lives Matter and Bringing the N-Word to the MCU.” The Daily Beast. September 30, 2016. http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2016/09/30/luke-cage-creator-on-black-lives-matter-and-bringing-the-n-word-to-the-mcu.html

Coker, Cheo Hodari. Luke Cage. Marvel Television and ABC Studios. Retrieved from Netflix. 2016.

Makarechi, Kia. “What the data really says about police and racial bias.” Hive. July 14, 2016. http://www.vanityfair.com/news/2016/07/data-police-racial-bias

Moss, Charles. “Luke Cage Is Truly a Hero for His Time.” The Atlantic. September 30, 2016. http://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2016/09/luke-cage-gets-a-new-story/502229/

Oatley, Keith. “Fiction: Simulation of Social Worlds.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences. August 2016. http://www.cell.com/trends/cognitive-sciences/abstract/S1364-6613(16)30070-5

Pulliam-Moore, Charles. “How ‘woke’ went from black activist watchword to teen internet slang.” Fusion. January 8, 2016. http://fusion.net/story/252567/stay-woke/

Rivera, Joshua. “Why the Creator of Luke Cage Wanted to Make a ‘Hip-Hop Western.’” GQ. October 3, 2016. http://www.gq.com/story/luke-cage-cheo-hodari-coker

Sapolsky, Robert. “This is Your Brain on Metaphors.” The New York Times. November 14, 2010. http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/11/14/this-is-your-brain-on-metaphors/?_r=0

Tanz, Jason. “Why Netflix’s Luke Cage Is the Superhero We Really Need Now.” Wired. August 16, 2016. https://www.wired.com/2016/08/mike-colter-luke-cage/