In the 7th grade I became a philosopher. It is not that I had never read anything philosophical before, because by the 7th grade most Americans have, but the day my english teacher asked us to pull out our books to discuss a reading we had been doing the week before is one of my earliest memories of a truly intellectually engaging moment. Of course, it would be easy to dismiss reading The Kite Runner as reading just another somber novel that everyone’s uninspired english teacher loves to analyze the figurative language in. In part, that is what The Kite Runner and the hundreds of literary works required to be read in middle school, high school, and college, are rightfully used for. But those compositions are the very same compositions that have turned the American student body of English, yes, including you, into philosophers.

It is probably in my best interest to clarify what I mean by philosophy, as I am sure the above statement is going to make some heads turn. The idea of philosophy in the respect that I mean to use it is certainly not the exact same respect that comes to mind when someone says “Hey, how about the philosophy of that guy Aristotle”, nor is it the debatably useless major that so many colleges still love to offer (I can say this because I am a philosophy major myself.) The best way to characterize it would be to keep it to its less modern, and therefor less refined, primal components. Put in simplest terms, it is powerful writing conveying some serious thought or ideology, or “scholarly writing”, as some may call it. This writing is generally associated with only proportions of people that specialize in philosophy, the philosophy “scholars” if you will. Granting all this, it becomes a loose term as we realize that philosophical writing lays in a lot more than just a theory of ethics text book.

Source: http://khaledhosseini.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/TheKiteRunner-cvr-thumb.jpg

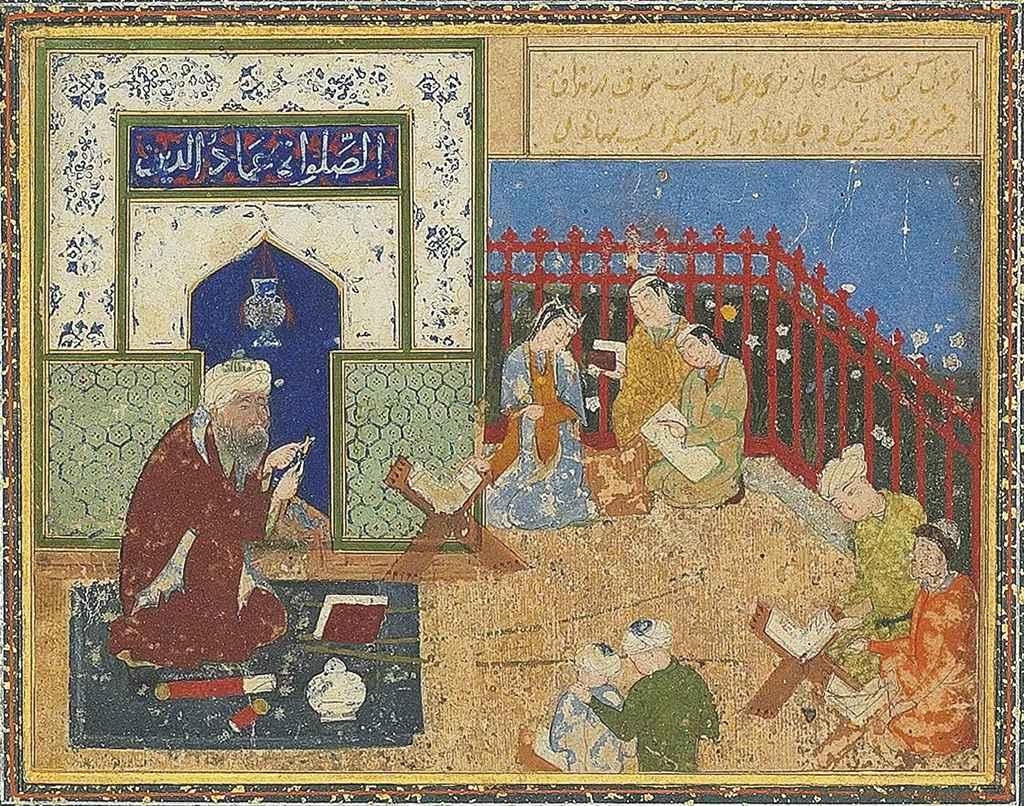

To understand the claim that Khaled Hosseini’s 2003 novel, The Kite Runner, is just as philosophical as, let’s say Nietzsche’s Genealogy of Morals (a philosophical work that discusses guilt and punishment, amongst other aspects of morality), it would help to provide some context of where the novel is coming from. Hosseini, who was born and lived many of his formative years in Afghanistan, wrote the novel with his homeland, which at the time of writing had been devastated by changes made by the Taliban, reflecting heavily on some characteristics of his early life, but also basing much of the book purely of imaginative fiction. The Kite Runner is like most melodramas of the 21st century. The common themes, striving for a seemingly distant father’s affection, reminiscing of a time in a place that is no longer present as it used to be, and regret, are all present throughout the book.

The plot line is a a simple one really, with a man, Amir, recalling his childhood in Afghanistan, and his relationship with one of his best friends, Hassan. As he recalls his childhood, he battles with understanding his relationship with his father, and his innocent juvenile selfishness that ultimately results in years of uncertainty, regret, and most important for the purposes of this paper, guilt.

There is a reoccurring, as English teachers love to call it, “theme”, regarding guilt and the emotional revelations experienced upon growing up throughout the novel. From the very beginning of the book, literally the first words “I became what I am today at the age of twelve, on a frigid overcast day in the winter of 1975…” (Hosseini 1), there is a suggestions of some traumatic event that haunted the protagonist for the rest of the novel. In the following paragraph, the ball is further dropped and a guilty conscious is confirmed with the line “It was my past of unatoned sins” (Hosseini 1).

But what does that mean to us, the reader, if there is a reoccurring theme of guilt? How does that have anything to do with revelations or philosophy. Well, those expository moments are the book’s way of leveling off with the reader and establishing a platform off which an argument is built. It would be strange to jump straight into whatever the book is trying to say of guilt and redemption without putting those two things in some context.

With a foundation set, Hosseini can, and does, spend the rest of the novel making some point of this marginally familiar feeling of guilt and desire of redemption. One of the most substantial points the book puts out, is the idea that guilt can make us act irrationally (no surprise there) and, in fact, lead us to undertake some business that we would not normally do. Hosseini demonstrates this theory using events that occurred in Amir’s youthful years leading up to his departure from Afghanistan. Amir, driven by biting feelings of guilt that are rooted in how he acted as a passive bystander to [spoiler alert!] Hassan’s rape, can not fathom how Hassan has no resentment towards him. Out of hopes to feel some release through punishment, Amir aims to drive Hassan into being angry at him by doing various despicable things. At one point, Amir pelts Hassan with pomegranates, later he frames Hassan for stealing a watch and some other birthday goods. Ultimately, Amir does not receive the release he is looking for, and his guilt manifests itself as anger toward Hassan for being so mild and not seeking revenge.

In addition to these irrational, and quite frankly ironic, actions that Amir takes in coping with his guilt, we also see into the primitive human mind. Amir is angry because he feels guilty and wants Hassan to punish him. By this, Amir is looking for his guilt to be relieved, and while it may seem that Amir is a morally conscious person who wants to be punished for his wrong doings, he really only wants to be punished so that he can move on with his life. Punishment would be a good thing for Amir, as he would be released from any “debts” he owes to Hassan.

The use of the word “debt” was not of pure chance. It is the gateway to the philosophy of all of what was discussed above. We can now turn to concept of the primitive human’s mind and the selfish desire to be relieved of any emotional debt owned, aka guilt. In Friedrich Nietzsche Genealogy of Morals, a fairly well-known work in the philosophy world, Nietzsche talks of the roots of guilt, and how it is strongly associated with the German word “Schuld” which means debt (Nietzsche 39). The very theme described by Nietzsche is paralleled Hosseini’s work, but put in a more personal setting.

Just as in The Kite Runner, In Genealogy of Morals Nietzsche also alludes to the idea of how being guilty limits the freedom people have in decision making. So like how Hosseini writes of Amir’s inability to make rational decisions when he is under the influence of guilt, Nietzsche argues that having an undisturbed conscience leads every individual to have the great responsibility of being liable for all their own actions. (Nietzsche 23)

Source: http://asiaportrayed.weebly.com/uploads/2/8/0/6/28061643/9861971_orig.png

Hosseini wrote The Kite Runner on and off for a little over three years, balancing out his morning writing sessions and his regular job practicing medicine, as we would expect of an entertainment writer. While many other popular novels had been published that same year, Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, The Five People You Meet in Heaven, and The Sisterhood Of the Traveling Pants, to name a few, The Kite Runner experienced some rather impressive successes. Its success as a novel is a great external factor as to why it can be seen as not just a plausible piece of philosophy, but a strong sample of philosophy for that matter. The parallels between the philosophy of Nietzsche and The Kite Runner should appear more than obvious at this point. What may not be as obvious, or at least not as much of a priority to think about when considering The Kite Runner as philosophy, is the idea that a work of literature just served an equally important lesson in the philosophy of ethics and guilt as Nietzsche, but in a more accessible and (a claim that I have only personal evidence to support but nonetheless is plausible) more entertaining fashion. When will you ever read the Genealogy of Morality on your own terms? How about The Kite Runner? It is safe to say that most of the young adults in America’s middle school, high school, and college systems now, would probably prefer to read a books like The Kite Runner as opposed to Nietzsche.

What does this say about literature as philosophy? For one thing, it certainly appears to be more accessible. That is a big claim to make considering that many have yet to see literature is philosophical (but if you read this paper and understood anything of it, I am sure you would at least reconsider taking a second look at the evidence supporting such a claim). Literature has undoubtedly historically been more accessible to general populations, as opposed to Philosophy, which requires a specific type of education and mindset. Literature makes philosophy more accessible, and because it is framed more attractively, it can spread ideas more conveniently. So, as we see that literature is more accessible than traditional forms of philosophy, we also begin to see that it is more effective at the job of spreading knowledge. It can be said that literature is like philosophy but more accessible and more effective. The effectiveness of literature to spread complex ideas comes partially from its natural accessibility, but also from its framing. The ideas are hidden in literature and cloaked in such a way that the reader almost has no chance to argue agains the philosophy. In order to enjoy and enjoy a novel in its rawest sense, there are philosophical ideas that are accepted as a baseline for understanding.

So what is the role of philosophy? In order to unpack the deep philosophical meanings within literary texts, experience in classical philosophy certainly will not hurt.

Any job that can be done by philosophy can most certainly be accomplished on a wider scale by literature. Literary philosophy, however, can be a two sided dagger. As suggested above, it will often require the acceptance of various philosophical ideas. Within literature, the acceptance of the ideas comes subconsciously. In other words, in books like The Kite Runner, philosophy gets served under the veil of entertainment. We can accept ideas without fully understanding them. The concern for lack of a deeper more holistic understanding, as opposed to a special case understanding, is likely to be the reason that regular philosophy is still around today. In other words, while philosophy in literature can be just as powerful and more accessible that traditional philosophy, we carry on with the study of regular philosophy because the philosophy scholars are afraid of losing their imagined “edge” over the rest of us philosophizing school kids.