By Emma Lezberg

“Nature is perhaps the most complex word in the language,” said author Raymond Williams, and it has also become one of the most powerful—not despite its multivalence, but because of it.

First, there’s the meaning of essence, as in “the nature of the thing”. Then, there’s that trickier definition, the one that refers vaguely to those yellow leaves falling past my window, to those cows grazing in the field down the hill, and even, perhaps, to the tiny green shoots cracking the pavement in a parking lot across the street. It’s both the environment and the divine breath that infuses it.

This dexterity gives an author incredible leeway. Nature can be powerful or fragile, Eden or “avenging angel”, sublime or artifice—but whatever it is, it is a concept to be manipulated, even created, at the whim of the writer (Cronon, 48). The tornado threatening Dorothy’s home is menacing foreshadowing, the storm sinking Aeneas’ ships divine wrath, the wind whistling by Pocahontas’ ears a kindred spirit. And the connotations that arise from these uses have real-world effects: depending on how one defines nature, native peoples can be embodiments of a lost harmonious age or, conversely, savages marring pristine wilderness.

To environmental writers whose goal is to alter society’s relationships with nature, the flexibility of this concept has been their biggest ally.

Rachel Carson, a twentieth century scientist, set out to write a book detailing the dangers of chemical pesticides. Whether wittingly or not, her book also turned out to concern the Cold War, feminism, and injustice. That’s what you get when you write about such a malleable, hard-to-pin-down topic as nature.

Silent Spring, Carson’s 1962 masterpiece, begins with a fairy tale called “A Fable for Tomorrow”:

There was once a town in the heart of America where all life seemed to live in harmony with its surroundings. The town lay in the midst of a checkerboard of prosperous farms, with fields of grain and hillsides of orchards where, in spring, white clouds of bloom drifted above the green fields….

Then a strange blight crept over the area and everything began to change. Some evil spell had settled on the community: mysterious maladies swept the flocks of chickens; the cattle and sheep sickened and died. Everywhere was a shadow of death. The farmers spoke of much illness among their families….

In the gutters under the eaves and between the shingles of the roofs, a white granular powder still showed a few patches; some weeks before it had fallen like snow upon the roofs and the lawns, the fields and streams.

No witchcraft, no enemy action had silenced the rebirth of new life in this stricken world. The people had done it to themselves. (Carson, 1-3)

At face-value, this introduction is straightforward, a simple lesson in causality. The imagined town is utopian, but quite accurately reflects the American rural ideal. The fields are bountiful, the townspeople content, and “white clouds of bloom” signal the fertility of the landscape. Then, with the suddenness of witchcraft or a biblical plague, the fields turn brown, the livestock fall ill, and people begin to die. Turns out, though, that it was not by a divine decree or evil spell; rather, the “white granular powder” that replaced the spores in the air were the cause of the malady.

Wait a minute, you might be thinking: why begin with a fairytale? Sure, the white powder is pesticides, we get that—but this is no way to begin a scientific work!

Carson’s critics contended just that. They pointed to this fairytale introduction to argue that she wasn’t a true scientist and that her book was too emotional and too idealist to present itself as science (Smith 737-738). The counterargument would be that the main chapters in the book delve deeply into the molecular structure of pesticides, scientific studies, and field research, and that the introduction is her way of making her point accessible to a general audience. Still, one must admit that it’s a strange way to begin a scientific book…

But perhaps we’re missing something here. Perhaps the book opens with biblical imagery rather than chemical jargon because it is asking to be analyzed through a literary, sociopolitical lens in addition to a strictly scientific one.

Let’s start at the beginning, then. We said that the “white clouds of bloom” blowing in the wind were signs of fertility and prosperity. Then, suddenly, some “evil spell” was cast, the landscape was “silenced”, people grew ill, and “everywhere was a shadow of death.” What caused this? No “enemy action”, Carson makes a point of saying, but a “white granular powder” falling from above.

This book was published in September 1962, the month before the Cuban Missile Crisis, and nuclear threat had been escalating for years beforehand. Even topics unrelated to the Cold War were employing Cold War terminology, as that was the language of the day. Likening any threat to nuclear disaster, the most frightening and cataclysmic danger of all, granted it more urgency. Carson does just that, and the powder falling from the sky and the mysterious illnesses are only the beginning. In Ch. 3, Carson describes how little we know about the ultimate effects of pesticides such as DDT, citing that Food and Drug Administration scientists declared that it is “extremely likely the potential hazard of DDT has been underestimated” and adding that “No one yet knows what the ultimate consequences will be” (Carson, 23). Remind you of certain bombs being dropped and how few tests had been done beforehand? Later in that chapter, she likens effects of chemical pesticides to the effects of radiation, to which we are “rightly appalled” (37). Through this introductory fable and throughout her book, Carson is implying that spraying hazardous pesticides everywhere—treating nature as our enemy, as it were—would lead to a self-imposed result as catastrophic as nuclear disaster itself.

How to deescalate the conflict between humans and nature to avoid self-destruction? To put it in historical terms, détente. Turning to Carson’s concluding chapter, “The Other Road”, she states:

We stand now where two roads diverge…. The road we have long been traveling is deceptively easy, a smooth superhighway on which we progress with great speed, but at its end lies disaster. The other fork of the road—the one “less traveled by”—offers our last, our only chance to reach a destination that assures the preservation of our earth. (277)

Of course Carson is overtly discussing pesticide use, but that’s nuclear terminology if I’ve ever seen it. By the time this book was published, the Cold War had been raging for fifteen years; escalation was clearly the road most traveled by. Straying from that path—détente—was the only way to assure the “preservation of our earth”. Carson is not just discussing pesticides; she’s discussing political issues and the stubborn folly of man, in regards to nature and also in regards to other human beings.

Her book ends with this sentiment:

Through all these new, imaginative, and creative approaches to the problem of sharing our earth with other creatures there runs a constant theme, the awareness that we are dealing with life—with living populations…. Only by taking account of such life forces and by cautiously seeking to guide them into channels favorable to ourselves can we hope to achieve a reasonable accommodation between the insect hordes and ourselves….

As crude a weapon as the cave man’s club, the chemical barrage has been hurled against the fabric of life—a fabric on the one hand delicate and destructible, on the other miraculously tough and resilient, and capable of striking back in unexpected ways…. [The] practitioners of chemical control…have brought to their task no “high-minded orientation”, no humility before the vast forces with which they tamper.

The “control of nature” is a phrase conceived in arrogance, born of the Neanderthal age of biology and philosophy, when it was supposed that nature exists for the convenience of man…. It is our alarming misfortune that so primitive a science has armed itself with the most modern and terrible weapons, and that in turning them against the insects it has also turned them against the earth. (296-297)

Note how little insects are mentioned. Take out those few references and this could easily be a passage arguing against escalation of the Cold War. Politicians, who have “no humility before the forces with which they tamper”, must remember that they “are dealing with life”. They must “cautiously seek to guide” their enemies “into channels favorable” to themselves in order “to achieve a reasonable accommodation”. After all, they are capable of “striking back”. (Mutually assured destruction, anyone?)

What are those “modern and terrible weapons” she mentions: pesticides or nuclear bombs? They could be either, or both.

Although Carson wasn’t an overtly political person or a feminist, many readers ascribe antiwar, ecofeminist viewpoints to her, and it is easy to see why. Throughout her book, Carson argues for an appreciation of the balance of nature—what was considered a feminist ideal—over the harsh “control of nature” that men had championed. Her definition of nature—as both powerful and fragile, but, more importantly, as complex and interconnected—underlies her rhetoric, conceiving a nature that is not to be dominated but to be protected. She calls for humility and recognition of all life, while many politicians and scientists sought only destruction.

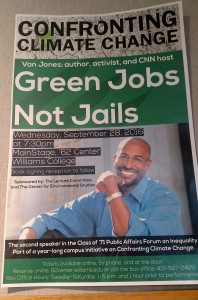

The question remains: if we allege that Carson was purposely bringing the Cold War into her book about pesticides, why would she do so? The fact that Cold War terminology was effective in conveying a sense of urgency is not the only reason. Ultimately, the two issues are related. Those who wanted to blow up the Soviet Union would also be blowing up our atmosphere, and as long as the world’s superpowers were focused on one-upping each other, they would not be able to work together to tackle environmental issues. As modern political and environmental activist Van Jones argues, “It takes all of us to save all of us.” Disposability is at the heart of the issue. To Carson, there is no disposable aspect of nature—everything is connected in the “fabric of life”—and there is no disposable human life either. Acting as if there is will only put us in more danger. The fates of man and nature are inextricably linked.

This is an ecofeminist concept: the idea that male domination has harmed both marginalized groups and the environment, and that it will take the nurture of women to heal this rupture between humans and nature. According to Smith, “through her use of metaphors about the balance of nature—precisely the language that so incensed many of her critics—Carson crafted a vision of nature that would resonate well with the philosophy of ecofeminism that began to develop a decade after Silent Spring was published” (734). Although calling Carson an ecofeminist would be anachronistic, her focus on preserving this “balance” and her insistence that all life is connected are right in line with ecofeminist views.

Yes, Silent Spring is anti-pesticides. But, more broadly, it is anti-domination, suggesting that what drives men to harm each other, to harm women, to seek uncompromising control in many spheres is also what drives them to harm the earth.

This is the heart of the argument. And now, as with all arguments like these, we must take a step back and channel our inner skepticism. Hold on, you might be thinking. We can extrapolate as much as we want from this text, but did Carson really mean to include all these sociopolitical messages in Silent Spring? Her first priority must have been to challenge the chemical industry, and she surely anticipated that critics would question her scientific qualifications. After all, she was a female scientist without a Ph.D., best known for her poetic books on marine biology (Smith 735). To be taken most seriously, wouldn’t her most logical course of action have been to focus on the science, to make her case against pesticides as objectively as possible? What if she really did intend to only write about pesticides, and other morals crept in inadvertently?

And that’s just it. I would imagine that she meant to draw this connection, that she recognized the “compromise” thread underlying potential solutions to many societal and environmental problems (why else start with the fairytale?), but here’s the key: it doesn’t matter if this connection were purposefully fashioned. The implications are present in Silent Spring whether or not such political ideas ever crossed Carson’s mind. By employing images like “white granular powder” falling from the sky and using phrases like “enemy action” and “most modern and terrible weapons”, the text is pointing to nuclear threat whether its author intended it or not. By its focus on “sharing our earth” and achieving “accommodation” and balance, the text is championing what would later be called ecofeminism, even if its author weren’t a feminist. And by connecting these two, by arguing against rash “control” and for “high-minded humility”, the text is urging readers to recognize the human arrogance underlying so many sociopolitical issues—even if she really did only aim to discuss pesticides. Language has an autonomy of its own, independent of its purported subject (in this case, pesticides), and sometimes even independent of its author’s intentions.

In fact, the under-the-surface nature of these secondary messages may have done the book a great service. Had Silent Spring made these connections less subtly—like the little-known book Our Synthetic Environment, published a few months prior and on largely the same topic—Carson’s book may not have had the impact that it did (Smith 745). But embedded in the connotations of its words, the text presented these implications to readers without turning them off as being too “political”. Silent Spring was a bestseller and succeeded in getting the harmful pesticide DDT banned, but it also led to the creation of modern ecological study. It changed the way people viewed the relationship between man and the concept of nature, and connected for perhaps the first time environmental injustice with social injustice. This may have been the book’s most far-reaching legacy.

Not every word has quite the dexterity that “nature” does—not every word can be invoked to argue such a wide variety of stances—but all language, as a cultural invention, always points back to the society that gave it birth. There is no way to describe concepts like disaster or equilibrium without invoking societal implications, just as there is no way to describe nature that is completely neutral and without connotations. That’s how a book about pesticides ends up discussing international politics and equal rights…and how an essay on a book about pesticides ends up discussing language itself.

WORK CITED

Carson, Rachel. Silent Spring. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1962. Print.

Cronon, William. Uncommon Ground: Toward Reinventing Nature. New York: W.W. Norton, 1995. Print.

Jones, Van. “Green Jobs Not Jails.” Confronting Climate Change. Williams College, Williamstown MA. 28 Sept. 2016. Lecture.

Smith, Michael B. “‘Silence, Miss Carson!’ Science, Gender, and the Reception of Silent Spring.” Feminist Studies 27.3 (2001): 733-52. Print.

Thorne, Christian. “Intro to Literary Theory.” Williams College, Williamstown MA. Oct. 2016. Lecture.

Williams, Raymond. Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society. New York: Oxford UP, 1976. Print.