Amando and The Eclipse (PDF)

AMANDO AND THE ECLIPSE: AN ADVENTURE IN MEXICO

Jay M. Pasachoff and Donald H. Menzel

A total eclipse of the sun happens when the moon hides the bright sun in the daytime. Astronomers like us can then photograph the sun’s corona. The corona is like a halo or wreath around a black circle. The black circle is the dark side of the moon. To see the eclipse of March 7, 1970, we went to Mexico, where we met Amando.

We flew in jets to Oaxaca (Wa-ha-ka), a state capital. Then we followed the road south. The local people took the rickety bus, piled high with baggage and baskets. The dozen of us from the Harvard and Smithsonian Observatories drove in a jeep and a truck. The people were mostly Indians. They lived in huts made of wood and straw. We forded a few streams, where floods had washed out the bridges.

A hundred kilometers (65 miles to us Americans) to the south, the paving, the electricity and the telephone lines all ended. We came into the village of Miahuatlan (Mia-wah-tlan). Our friend, Engineer Reyna, had found an empty schoolhouse where he could live and set up our equipment. It lay up a dusty road, on top of a hill to the left of a church.

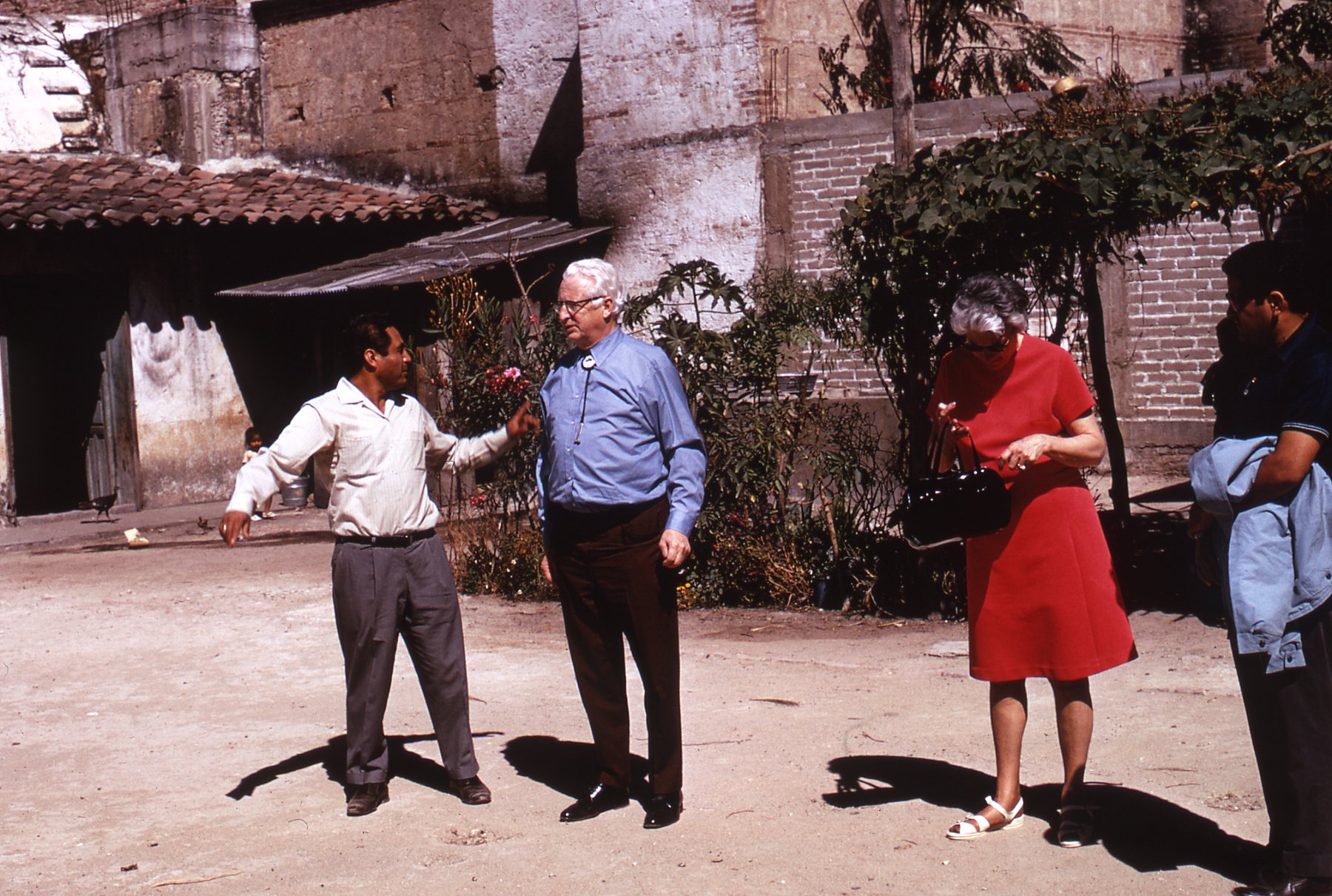

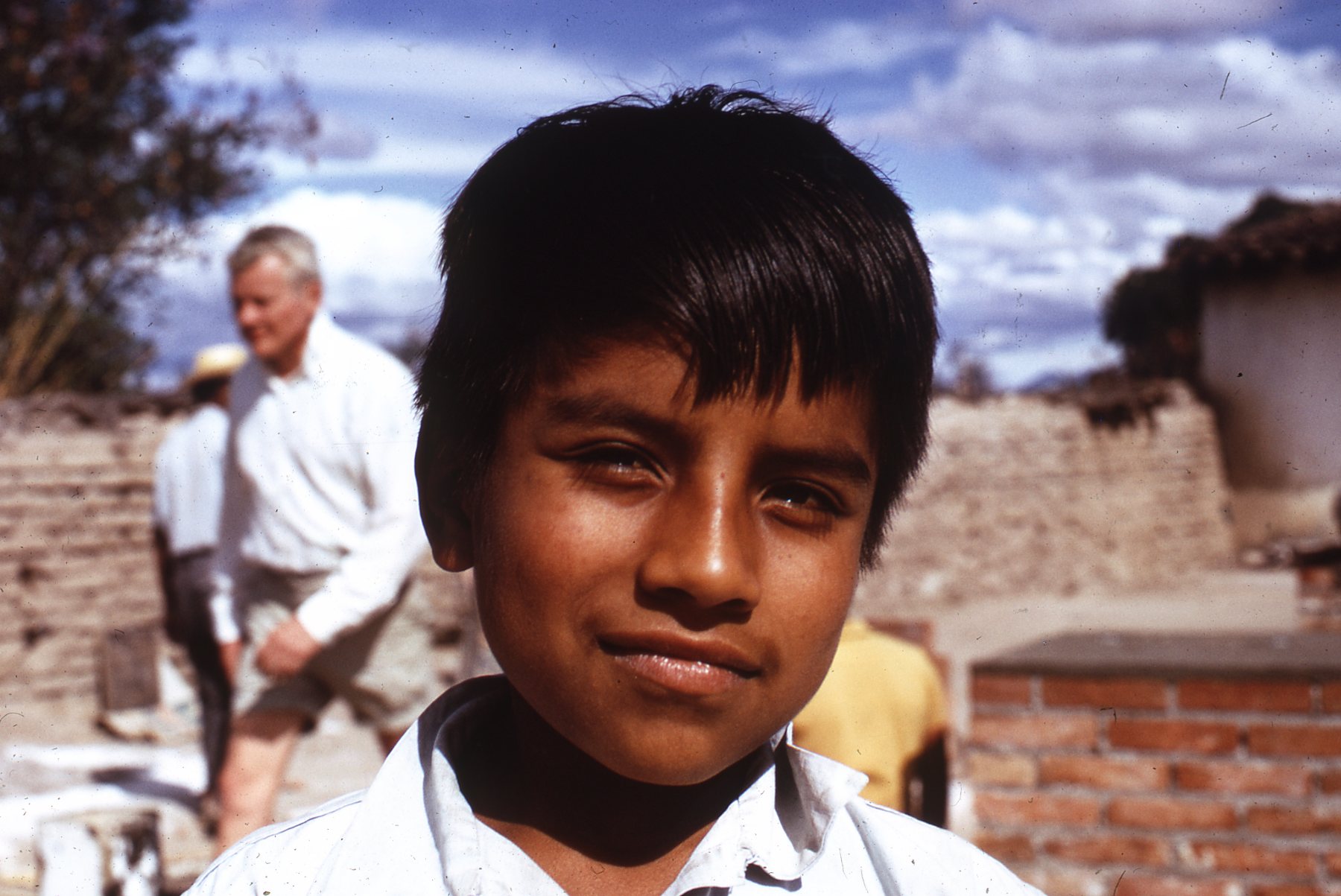

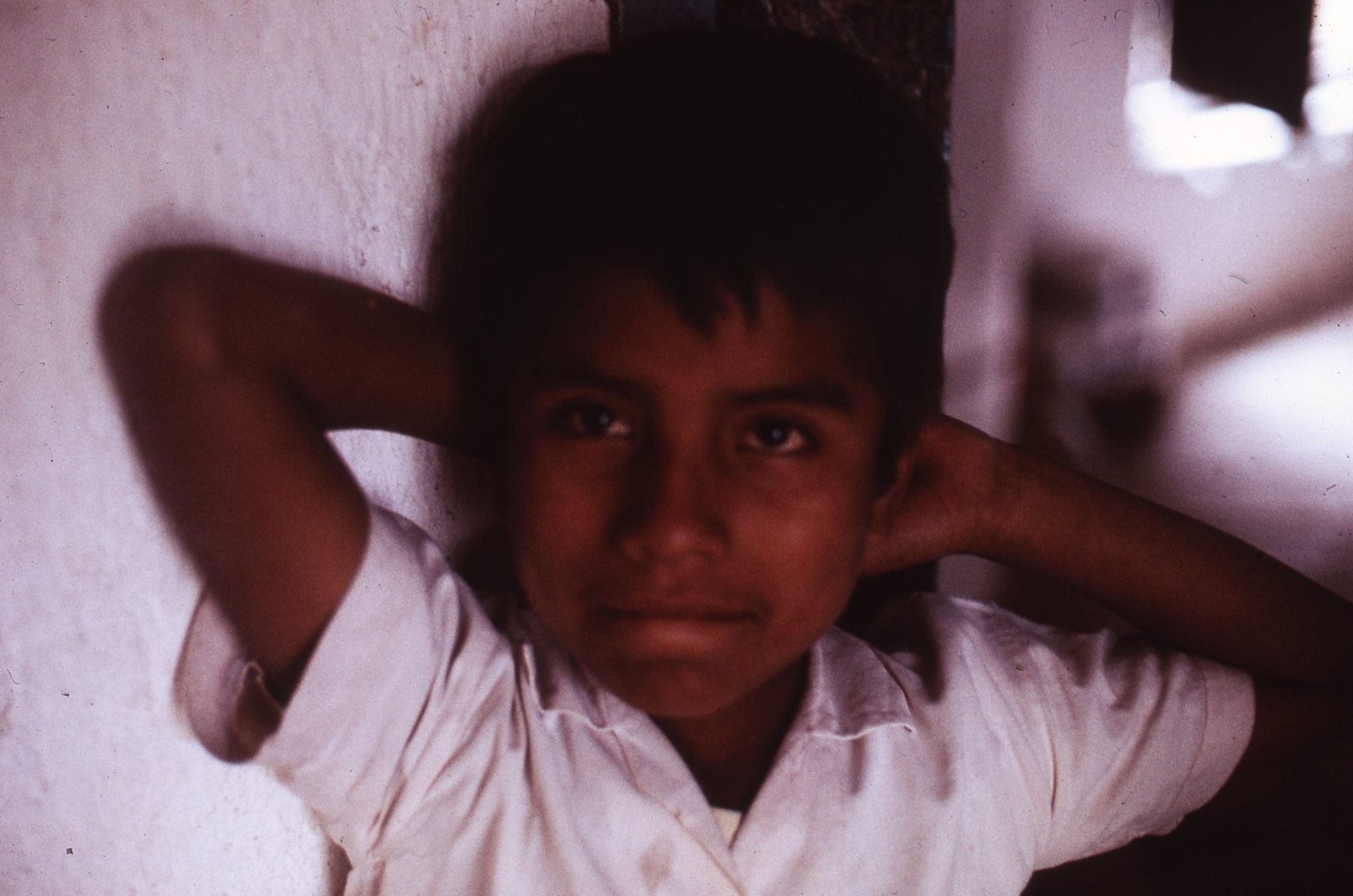

We met Senor Garcia and the Presidente, which is what they call the mayor. The schoolhouse patio was perfect for us. Right away we started to figure out which telescope would go where. Soon a boy came up to us and smiled. “Como te llamas?”, “what is your name?” we asked him. “Amando-Martinez Morales para servirle,” “at your service,” came the reply. And so we gained a new member of our expedition.

Amando’s mother and little sister were outside in the patio, washing a frying pan. Cold water ran from a faucet. Whenever they wanted some hot water, they built a little fire with sticks of wood. As soon as she smiled, we knew that our stay here would be a good one. The Presidente and some of the children from the village came over to see us, and we all made friends.

Oh yes, Amando’s little brother, Juan, didn’t want to be left out. Amando always took good care of him. Amando and his brother and his sister lived with his father and mother, his grandmother and his Uncle Frank in one of the rooms at the schoolhouse. Amando’s parents were the caretakers. All the local children wanted to know who we were and where we were from. We had to show them on a map where we were in Mexico and how far we had come.

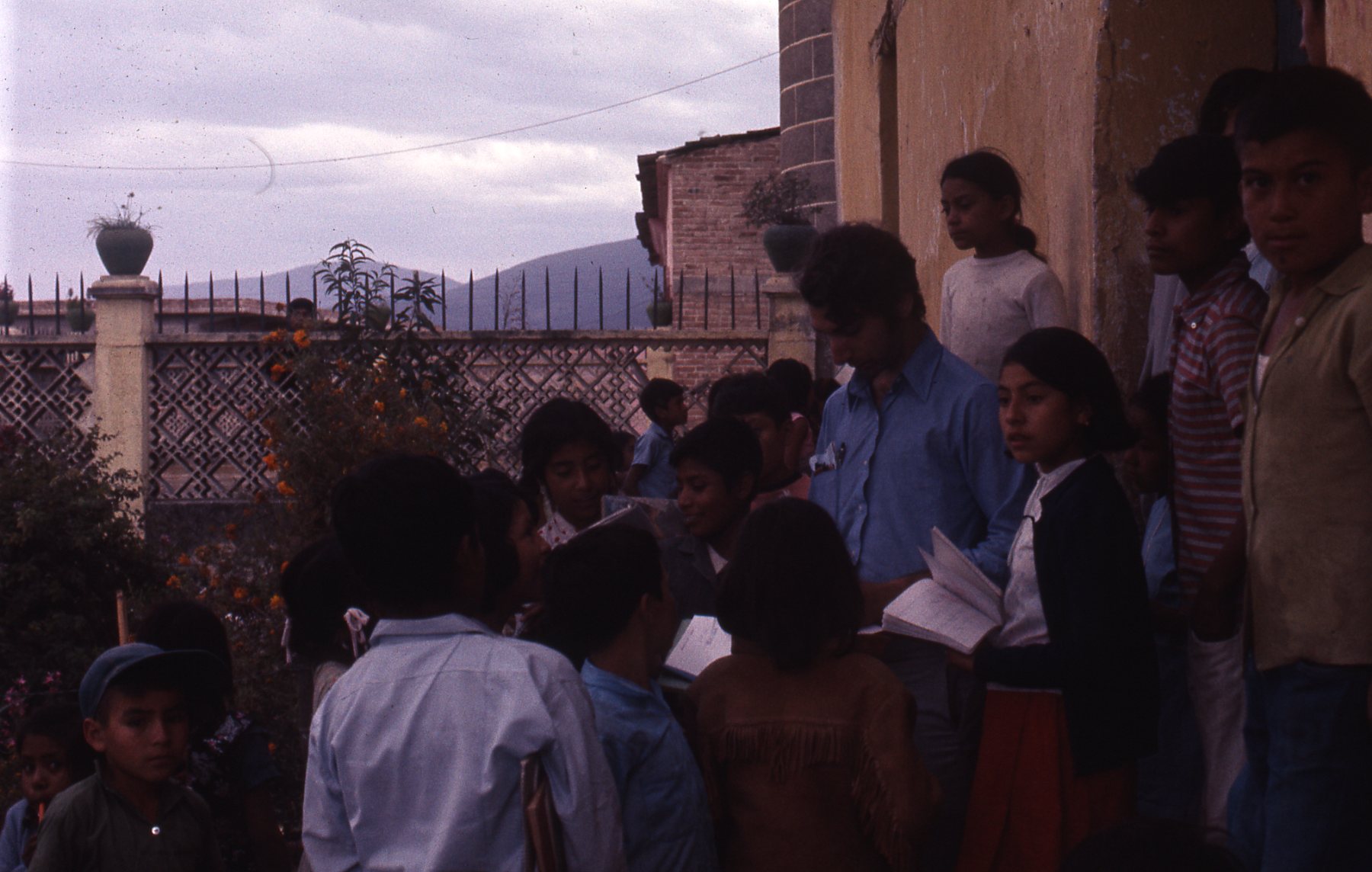

They asked lots of questions about astronomy too. Amando was always by my side to help explain. We all spoke Spanish, of course. The children had been studying about the eclipse in school.

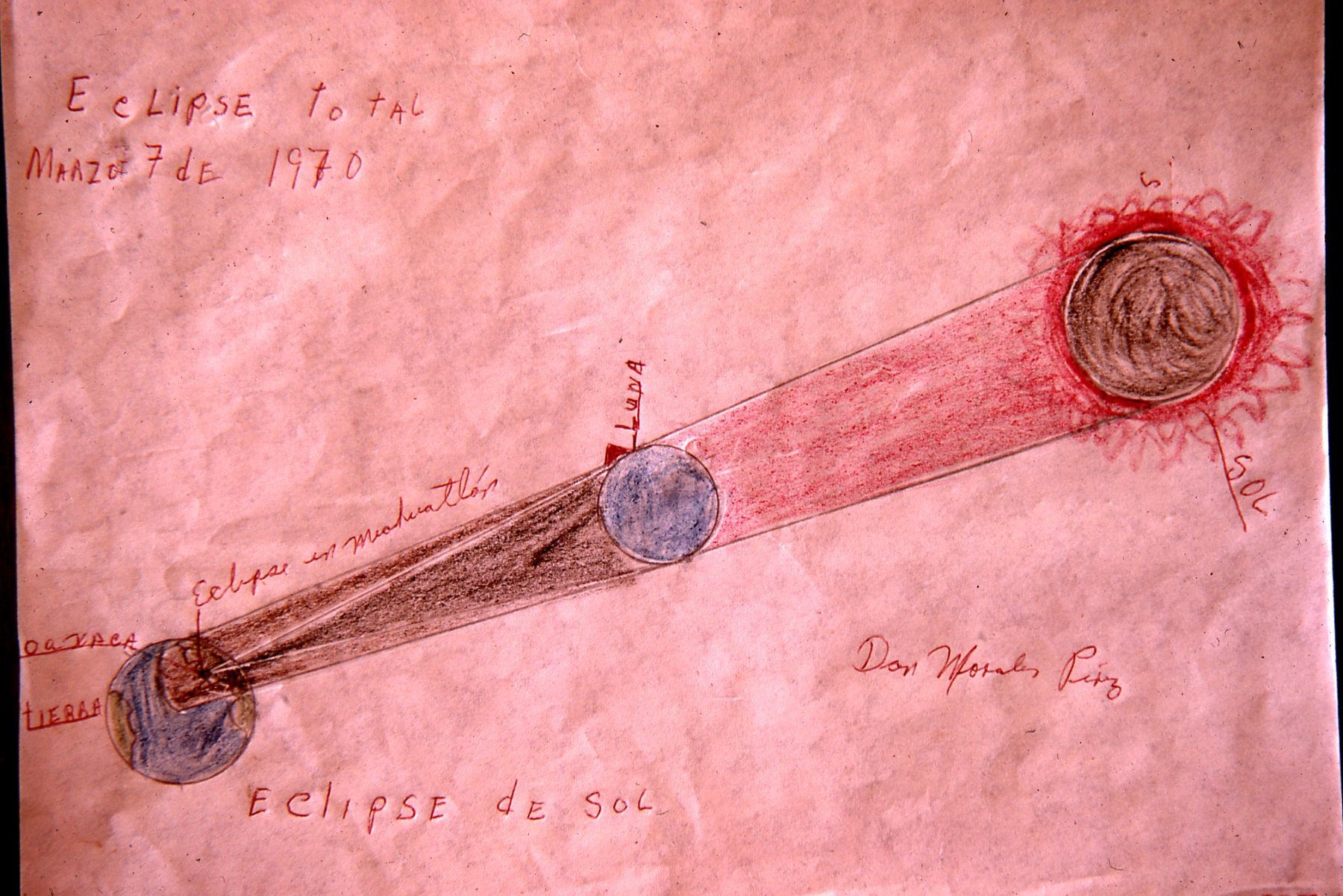

Amando drew this picture of what was to happen. It shows how the moon’s shadow falls on the earth to make the eclipse. The shadow would be over Miahuatlan for three and a half minutes. That is a long time for an eclipse.

Another boy had drawn what the sun would look like if we could cut it open. Of course, we can’t, because the sun is just a big hot ball of gas. The sun does have a very hot center, called the nucleus. The shining surface on the outside is called the photosphere. An eclipse is special because the moon covers this surface so that we can see the fainter layers outside, called the chromosphere and corona. We were all pretty excited and could hardly wait.

There weren’t many cars in town. Most people walked. They carried heavy things on oxcarts or burros. Here Dr. Menzel is coming up the street. He has probably seen more total eclipses of the sun than any other person. But there is nothing that even he can do about the clouds. We always worried whether the weather would be clear on eclipse day.

Across the street from our schoolhouse, the Presidente had a general store. And what a store! It sold pots, blankets, radios, irons, stoves. paper, toothbrushes. Just about everything; There were no doors during the day because it never got too cold outside. Overhead shutters rolled down at night. We loved going in to say “buenos dias,” which is “good morning” in Spanish. We bought lots of little things there. They even had a telephone in the store, Frank is using it in the background. Mere were only about 10 telephones for the whole town. Our telephone number was “seven.” That was pretty easy to remember.

The Presidente’s wife stayed behind the counter of the store with three teen-aged girls to help her. Here Acela is counting out a hundred pieces of writing paper for us. Most of the time, ox-carts rumbled by our front door. One day a big truck came, carrying all the telescopes we had sent. Dr. Menzel couldn’t wait to check that everything was safe. Our boxes weighed two and a half ton.

We would have to work hard to get ready for the eclipse, we carried the big boxes inside. They all weren’t as heavy as this one.

The very first night we found the North Star, which is called Polaris. We pointed a special telescope, called a transit, toward it. In that way, we found the direction of north. The next day, with that transit, Amando helped us mark the places where we wanted to set up our telescopes. Some of the bases had to face exactly east, so that we could follow the sun as it rose.

I carefully climbed up the ladder against our back wall and looked over. I wanted to see where all the hee-haws came from all night. Sure enough, the people next door had donkeys, chickens, dogs and lots of other animals in their back yard. Grandmother carried water to the animals when they needed it.

On the other side was a fireworks factory. I could hardly wait to see them go off. Do you like fireworks as much as I do? The family there had prepared lanterns for a big parade. I admired the lanterns but didn’t go too close to the rockets. I told one boy what a handsome new bicycle he had. He knew it already!

While we were working, Jeff set up a small telescope we had brought. Every morning was clear, but by noontime, clouds usually filled the sky. We worried about the clouds, but kept working. Jeff was a high school student who had come with us to help work the equipment. He arranged the telescope as a projector to show the sun on a white screen. We all looked at the dark sunspots.

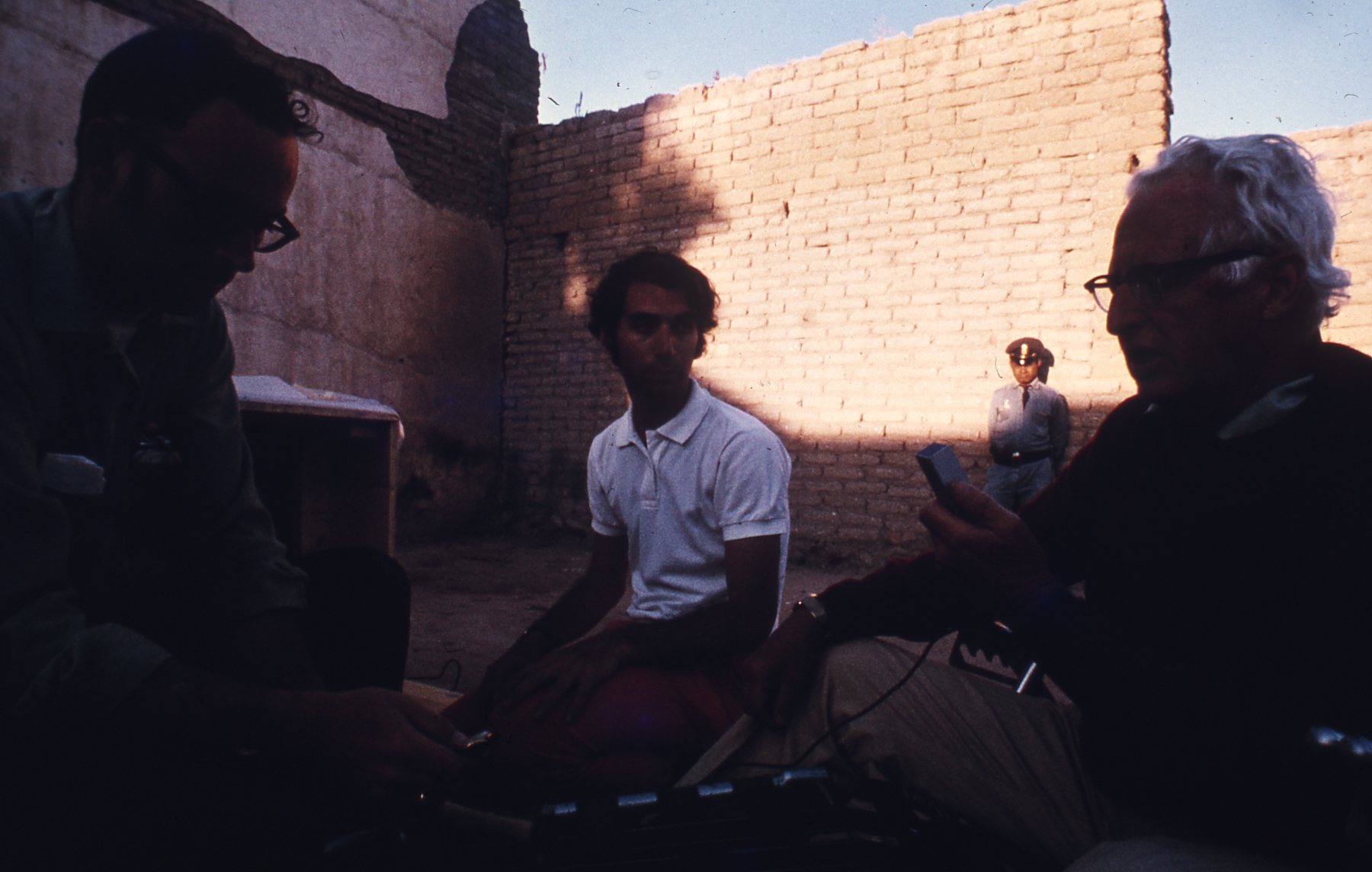

Lots of people visited us to see how we were. The Mexican Army even wanted to help. They came around a few times a day to make sure that everything was all right.

Soon Bobby had the telescope bases built of bricks and cement. Amando’s uncle Frank is on the right. He did most of the work. Darrell, on the left, set up some television cameras. He wanted to make videotapes of the corona during the eclipse. As soon as the cement was dry, he set to work. Behind him are parts of a little house we started to build, we wanted to keep our biggest telescope out of the dust and rain.

This telescope filled the little house. The telescope was so heavy when we put it together, that it couldn’t be moved to follow the rising sun. So we used a big mirror, which is behind a gray cover in this picture, to reflect sunlight into the telescope. The mirror was supposed to turn slowly to follow the moving sun. But its small motor kept on breaking. Finally, we got a new one just in time for the eclipse. It worked perfectly.

One day it rained. We had to stop testing the mirror, and cover it with plastic in a hurry. Amando’s mother tried to ignore it, even though it was in the middle of her patio. Filially, a rainbow came out to show that the rain was over. She had lots of work to do. There were clothes to hang on the line and dinner to fix.

Larry’s job was to make this little telescope work. It takes pictures of the sun through a Polaroid filter. This camera didn’t always work either. It was hard to make sure that all of our telescopes and cameras would work when the eclipse came. That was why we came here a whole month early.

Soon our little house went up. Amando helped put up the walls. They were aluminum on the outside to reflect as much of the hot sunlight as possible. The walls were black on the inside to keep out sunlight. Inside, the temperature was cool and even. Everybody worked very hard.

Next, we put the roof on. The workers were surprised because the roof slanted to let the rain run-off. In Mexico most roofs are flat. Before we put on the last wall, we moved in a big long tube. Inside the tube was a special kind of mirror that spread the sunlight into all the colors or the rainbow for us. We came this far especially to photograph that. It tells us what the sun is made of and how hot it is.

One Sunday, Maria and two of her friends came all the way down from Oaxaca to visit. They rode for four hours to see us. I hope they had a good time.

Amando’s mother was so friendly. She worked so hard. Our laundry was never as clean as she got it. Amando’s father built a flush toilet specially for us. Not any people had them in Miahuatlan. Most people used little out houses for toilets. We had two of them outside in the patio. We also had a shower. When we wanted to use it, we had to decide fifteen minutes before, so somebody could light a fire to heat the water.

Darrell and I had lots of things to put together. We worked in one of the rooms downstairs in the schoolhouse. As soon as we opened the shutters to let in light, all the children ran to see what we were doing. There was no glass to get in their way. We had quite an interested audience as we worked. Oh, all the men in Mexico have hats, so I got one too.

We were such celebrities that the children asked us for autographs. Jeff spent a lot of time signing his name. He learned some Spanish too from the children. I don’t know if they really wanted us, though. heard they had a contest at school to see who could get the most autographs. Even Angel, who drove our car for us, signed his name hundreds of times.

Two weeks before the solar eclipse, an eclipse of the moon occurred. Only twelve per cent of them moon was in the shadow of the earth. Even so, you could really see a bit out of the moon, it you were lucky enough to find a hole in the clouds. We had to stay up very late at night, and had only a few seconds when the clouds happened to break. At least I got a few pictures.

Most of us lived in the schoolhouse. We slept on folding beds that we bought or borrowed in Oaxaca. But we were still more comfortable than the local people. Amando’s family all slept in one room on a big mat on the floor. The family across the street had a double bed they all slept in. After the eclipse, we also left them our little house on the patio, so now they have more space to live in.

When we weren’t working, sometimes Dr. Menzel would play the guitar. There was no television to watch. We went to bed early until the fiestas started.

And there weren’t any bullfights in this part of Mexico. So, for a few minutes one day, Dr. Menzel and Amando’s father made their own. Don’t you think Dr. Menzel looks like a bull, with his hands up for horns? Ole!

The children had never seen American football before, so Bobby showed them how to throw the ball. We all came out to watch. We had set up flags from the United States, Mexico, Harvard University, the Smithsonian Institution and the National Geographic Society over our door. If you were looking around town for us, we were pretty easy to find.

Amando and the boys came over to play too. They liked the game, although we only tossed the ball back and forth. They play soccer in Mexico most of the time. The girls thought it hilarious when anybody dropped the ball. We played for hours. Sometimes a passing burro interrupted the game for a few minutes.

Next to the Presidente’s store, was one of the schools. It was run by nuns, and sister Maria set up a special kitchen to feed us. The children went to classes in the buildings behind, and played in the yard.

One day, Yvonne and her cousin asked me to come watch them practice their dances for the fiesta. They went twice a week to one of the empty rooms in the school buildings after classes were out. Amando was learning to work my camera, and he took these pictures. I certainly couldn’t. I was too busy dancing. It’s a pretty complicated camera. He did a good job.

We all spent a lot of time visiting around Miahuatlin. The houses were made out of mud bricks or stucco, and were one or two stories high. The only paved road ran from the north, and that stopped at the town square. We had to walk in the dusty village streets. A few of the main streets had sidewalks, but they weren’t in good shape. It was safer to walk on the road.

Often, we would have to step aside to let an oxcart pass slowly. This one was actually carrying a small gas motor. They probably used it with a water pump.

There were a few general stores around other than the Presidente’s. Everyone was helpful to us, and so very cheerful. I shall always remember their smiles. Amando went off to school every morning with his books under his arm. He usually found a friend to walk with. His school was new and pleasant. Mexico is building a lot of new schools, especially in small towns. Mexican children go to school on Saturdays as well as weekdays. but Amando didn’t mind.

When we arrived at the school one day, the children were playing during recess. put when they saw us, they came running. I thought at first that school was simply over but they came and came. Soon we were surrounded. I gave Amando my camera again while I answered questions. The children agreed to stop pushing when I promised to take their picture. Then they all stood back, and we tried to get everyone in the photograph.

Even more than school, though, Amando loved coming home to us work on telescopes. When we had time, he took us for walks around the town. People brought in their crops from the farms all around. Sometimes a big load of hay would come by.

At the edge of town was a big rocky area. Cesar and Amando and Larry walked up to the very top. There wasn’t too much to be seen though. Just some stones and holes in the ground. Of course, a large spider and its web on flowering cactus fascinated us.

Amando loved his job as my Chief Assistant, and enjoyed taking photographs. He tried nearly everything, such as helping unload an oxcart. So, we made a good team. Sometimes Amando was content to pose for a photograph with all the others.

Near Miahuatlan are many smaller towns. The Indians from these villages came to the market to sell food they grew in their own gardens and things they made with their hands. They are Zapotecs, and speak the Zapotec language. Most of them don’t understand Spanish. It took us an hour to drive only 8 miles to visit one of these towns. There, we found a beautiful church in the town center.

The government had built a modern school. I even saw a basketball court. Right next to it lay the ruin of a church, hundreds of years old. You can see Miahuatlan in the background.

There is no running water there except in the mountain streams. The Zapotecs wash their clothing as they always have. You can get clothes very clean in a stream.

The view from the hillside is pretty, but life is hard. The people are often sick. Not one single doctor in the world can speak Zapotec. The missionaries who invited us there do all the medical work. They pull teeth too because there are no real dentists. I felt that we were returning to the big city when we got back to Miahuatlan and found stores, electricity and running water. Still, everybody had to provide enough for himself. You could keep very busy just hauling enough firewood to keep warm at night. Often, a few burros loaded with sticks would came up our street.

About a block from Amando’s house was a bakery. “Pan” means “bread.” Fresh bread smells and tastes so good. They sold all sorts of hard rolls and cookies.Workers in the many open doom along the street smiled and said hello as we went by. This man mostly fixed shoes, but he also worked on whatever else needed mending.

A little further along was Pablo the Miller. It was always dark inside his door, but on Sunday morning, women and girls would form a long line around his walls and out the front door into the street. I wandered in one Sunday, and I found Pablo grinding maize for tortillas. You poured your corn kernels into the top of his machine. The girl behind you helped take the ground corn meal out at the bottom. An old motor clanked in the corner and turned the grinder. The people baked these tortillas at home on outdoor fires in their back yards. Tortillas look like pancakes. They are very popular in Mexico. Most people prefer them to bread.

The chickens and turkeys were pretty fresh. They are kept alive because there are no refrigerators. How can you keep a turkey quiet while you carry it around?

Near the center of every Mexican town is a big square with benches. The square is called the zocalo (zo’-cal-oh). In Amando’s village, the Presidente’s office was on one side, and the cathedral on the other. In the middle was a band stand.

People used the zocalo for the village market. They bring in their wares and spread them out on the ground. The market goes on every day, but is largest on Mondays. The Indian women who come into town from the smaller villages carry around huge baskets of delicious fruit and vegetables. They pile them up on mats and then sit back, waiting for customers. It is something like a picnic. They talk to their friends, and watch the crowds go by. And when they are thirsty, they drink from a bottle of water or soda.

This is the butcher shop. The meat hangs out in the open. People can’t afford to have beef very often. When they do, the meat is sliced thin because it usually is tough. The women always wear shawls. They use them to cover their heads, or to tie babies to their backs or even to carry things.

This lady has her shawl around her shoulders. It is her most useful, possession. Here she is showing the beautiful tongues she is selling.

Tomatoes are a specialty. I never before saw such lush, ripe ones. Many of the sellers would be sitting next to each other. Everyone would wander back and forth, looking for the best quality at the best price. Each woman would try to offer a better price.

Here Jeff is buying a few tomatoes for us to have at lunch. We prefer the big, juicy, red ones. Sometimes Amando got permission from his mother to stop for dinner. His father would give him a few pesos, and he would take a basket to carry home the things he bought. This made him feel grown up. People sold other things in the market besides fruit. There were always many kinds of beautiful flowers. It is very nice to have fresh flowers at home. We thought they were very inexpensive.

You could also buy tortillas, if you hadn’t made your own. They come in stacks. You out some special filing inside them and roll them up before you eat them. The Mexicans use them instead of sandwiches.

There were lots of animals in the marketplace, but they were all tied up. If the turkey got too noisy, you could always out the basket over it.

There are lots more peppers in Miahuatlan than in my home. Green ones, red ones, big ones, little ones. This man has a whole stall full of peppers. I couldn’t eat very many of them, though. They taste hot and burn your mouth and tongue. You have to learn to like them, because they sting your insides. The man behind the counter sold a few eggs too. One day the Oaxaca newspaper told about the eclipse. He was reading all about it.

Miahuatlan is famous for its knives, large and small. Amando helped me pick out several souvenirs. You always have lots of help whenever you want to buy something. They etched the knives with our names and the date. the knives don’t come sharpened. Everyone there sharpens his own. Mine is back in the United States. 1 haven’t used it yet to cut the grass so it is still dull.

One day was the Mexican Flag Day. The schools were closed for the holiday. We all went to watch the parade. The school children marched in the streets in their school uniforms, carrying Mexican flags. We were somewhat amused to find that the marching music was “The Stars and Stripes Forever.” We found Amando at home. He said he didn’t feel like going to the parade, but we learned that his parents couldn’t afford to buy him a uniform. We all felt very sorry when we found out. When we left, we gave him a new uniform.

The color guard marched around and back to the town square, where we heard some fiery speeches. Like our Fourth of July. Many of the towns people were there to listen, and to join in the celebration. These boys listened to every word. When I got hungry, I could always find food. The sugar coated cakes looked good. Lots of flies liked them too.

These boys didn’t listen to the speeches too carefully, but they had a good time anyway. Nothing could stop them from giggling when took their picture.

Some people were not very interested at all. Or perhaps they had stayed up too late the night before. I loved their watermelon and pineapple.

One day in town I met Yolanda, who is on the right, outside her school. She worked in the Presidente’s store after school. Yolanda and her friends told me that there was to be a big fiesta that night. I mustn’t miss it. I didn’t intend to.

But just to make sure everybody remembered. the girls all dressed up in their prettiest native costumes that afternoon. They rode in oxcarts decorated with flowers and paraded through the streets. They called, “Jay, come with us,” so I even got to ride an oxcart with them for a while.

After dinner that night, we heard shouts outside our dining room. A marvelous parade of school children was passing by. The children were carrying lighted lanterns. Many of the lanterns were astronomical— there were stars, planets, and even a comet. We followed the parade all around and back to the center of town.

There found a gala celebration going on, with entertainment and staging and dancing. Groups of boys and girls from the various schools performed the Mexican Hat Dance and some at the other national dances. We all enjoyed watching them.

Finally came the fireworks! It was pretty late when they began, but nobody could sleep through that noise. Pinwheels whirled. Rockets flared. A curtain of fire rained down from one of the buildings. At the end. a huge arch built out of wood and covered with all kinds of fireworks lit up. Excitement shot out in every direction. Some of the fireworks spelled, in Spanish, a sign welcoming us all to Miahuatlan.

The next day things were calmer. During a break in our work, we decided to go to visit the Mexican astronomers. They were setting up telescopes on a mountain outside of town. Amando went to ask his father for permission to go with me. When his father said “yes.” he jumped in the car. fie looked excitedly around at all the houses as we drove out of town. Soon we were in the countryside. We saw houses built of sticks. They were in the fields and near the slopes of mountains. The people all smiled and waved as we went by.

Then we climbed into the mountains. We couldn’t drive very fast on the dirt road. Slowly we mounted higher and higher. This was the first time that Amando had ever been out of Miahuatlan. He had never been farther than two miles from where he was born. This was his biggest outing.

On the top of the mountain we turned off where we saw the first telescope. We came on a straw hut, where a family of Indians usually lives very quietly. Now, behind them, lay a beehive of activity—the Mexican Expedition. The Mexican astronomers had brought a huge telescope. They came from the University in Mexico City. They wanted to photograph the stars that can be seen during the darkness of the eclipse. A big building with a framework of steel was needed to protect their telescope. They filled the walls in with brick later on. Their telescope was a real monster. It had to be that big to photograph the fainter stars near the edge of the eclipsed sun.

A little further up the hill the Mexican astronomers had some radio receivers to listen to radio waves from the sun. It doesn’t make’ a regular picture of the sun at all. A lot of complicated wires joined the antennas to the control center. I hope that the turkeys didn’t eat any of them up.

Amando and Mike and Larry climbed to the very top of the hill. They had a perfect view from there of all that was going on. These clouds were beautiful. too, but not for an astronomer. We wanted them to go away, so we could see the eclipse. Amando was excited. He could see the whole valley spread out behind him. His home town of Miahuatlan was 10 miles away. Never before had he been so far from home.

Finally, the sun set and the sky began to grow dark. We went back to town. We stopped for a moment on a small hill, and Amando could see his whole town in one glance. An old friend. Home.

Hundreds of astronomers came to Miahuatlan from dozens of countries all around the world. We enjoyed visiting them and they liked to visit us. One day we called on the French astronomers. They had some telescopes that were as bulky and as complicated as ours.

It was pretty hot where the French astronomers had set up their telescopes. But a cool stream flowed nearby. Almost every day, they all went down for a swim. There were lots of interesting animals and fish, and even some tadpoles. I held this one for only a few seconds before I put it back. He must be a big frog by now.

The Russian expedition was not far away. They also received us very kindly, and showed us all around. The Russian astronomers had many kinds of telescopes, for both light waves and radio waves. We all enjoyed talking together.

Time passed rapidly. Soon the eclipse was about to happen. Many friends came down from the United states for the last couple of days. We ran out of beds. and one of my friends had to sleep in a pile of rags outside in the patio. We were all nervous as we went to sleep the night before the eclipse.

When we woke up. we couldn’t have been happier. The sky was the most beautiful blue we had ever seen. Not a trace of cloud or haze. Our patio, which had been so calm, became a madhouse. Everybody was setting up equipment. and getting ready. Some of the children climbed up on the roof of the church next door to watch on.

Ron and Andy watched Darrell testing his television equipment. He had four cameras mounted there, each one looking at the sun through different combinations of colored and Polaroid filters.

In the lower patio. Fernando de Romana, an old friend from Peru, had joined our group. He set up his own telescope. During the morning, he practiced taking pictures to make sure the telescope was working. We had been practicing too.

Finally, the moon began to cover the sun. Through dark glasses, we could see a tiny black bit out of the edge of the sun. Slowly the bits grew larger. Every so often, the moon in its orbit around the earth comes exactly between us and the sun. The shadow of the moon falls on the earth. Anybody standing in that shadow cannot see the bright sum. In Miahuatlan we were in the right place and we had an eclipse.

Suddenly the moon completely covered the sun. The eclipse was total, and we could take off our dark glasses. We could see pink prominences peering out around the edge. These are clouds in the sun’s atmosphere. All around them, we could see the pearly white corona.

Everything was quiet. Even the roosters and burros next door had nothing to say. The sky was a very dark blue, even though it was eleven-thirty in the morning. The corona had all kinds of spikes sticking out. The spikes reach out millions of miles into space from the surface of the sun. It was beautiful. We could also see Venus shining like a bright star.

The only sounds were our own, counting the seconds and making sure our instruments were working properly. We would have months of work back home to find out what we wanted to know about the sun and the corona. In the meantime, we were content just to look at this beautiful eclipse along with everybody else.

Then, it was over. The moon moved off and the sun reappeared. The instruments were quickly packed. The next night, after the sun set, Venus was still just visible. The thin crescent of the new moon was a little higher in the sky.

As we left, Amando was waving. We said goodbye to him and to his family in their patio. They would remember this beautiful eclipse all of their lives.

Jay M. Pasachoff was on the staff of the Harvard College Observatory at the time of this Expedition. He is now at the Hale Observatories, Carnegie Institute of Washington, California Institute of Technology, in Pasadena, California. The Big Bear Solar Observatory there has just been built to study the sun.

Donald H. Menzel is at the Harvard College Observatory and the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory. He was Director of the former for many years.

The photographs in which Dr. Pasachoff appears were taken either with a self-timer, or by Lawrence A. Lief, Michael Mattel, or Amando Martinez Morales.