Introduction:

UDAKA Keiko is a Noh mask maker from Kyoto who comes from a long family line of individuals specializing in the art of Noh. Since her youth, she has been involved in the drama form under the tutelage of her late father, Michishige Udaka, a renowned Kongō school Noh performer and mask carver who helped establish the International Noh Institute. Udaka-sensei graduated from the Department of Fine Arts of the Kyoto City University of the Arts, concentrating on Noh mask carving. As a female mask carver in a traditionally male-dominated industry, her presence in this scene also represents the evolving legacy of Noh. Following her graduation, she has been involved in the art form as both an educator and a practicing artisan. For Udaka-sensei, a single mask may take around two months to complete due to the intricate process involved in the carving and coloring aspects of the mask creation. Although her practice follows traditional ways of mask making, she has expanded her art practice by utilizing different modern mediums of engagement to educate a wider audience who may not be familiar with Noh.

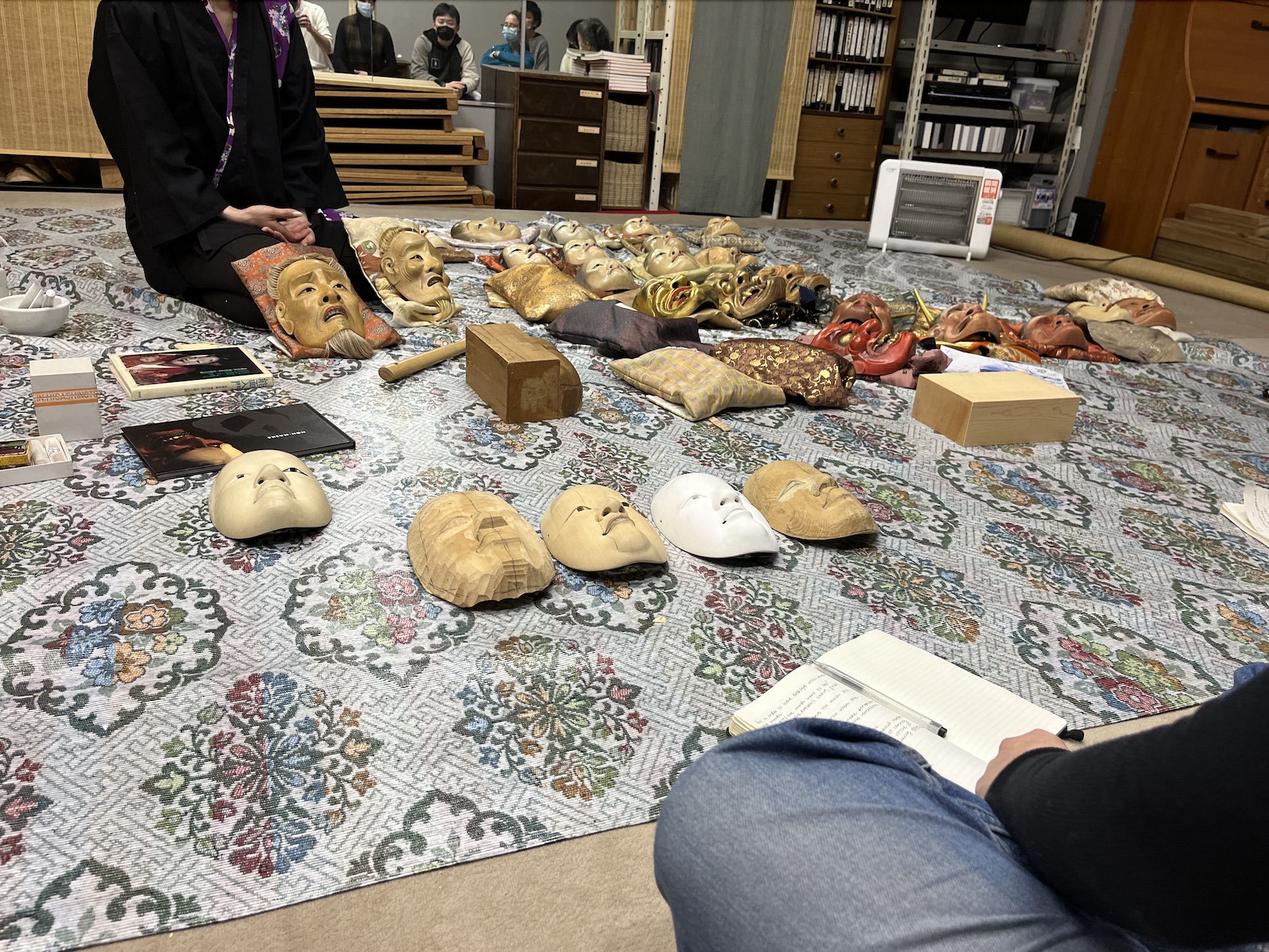

In terms of Udaka-sensei’s engagement with the traditional, she helps lead workshops and teaches mask carving to students in the International Noh Institute. In these workshops, which meet three times a month, students learn how to carve different styles of Noh masks, using traditional chisels, templates, and engaging with natural pigments to create the masks. These masks are then displayed in a biennial exhibit to showcase the students’ work.

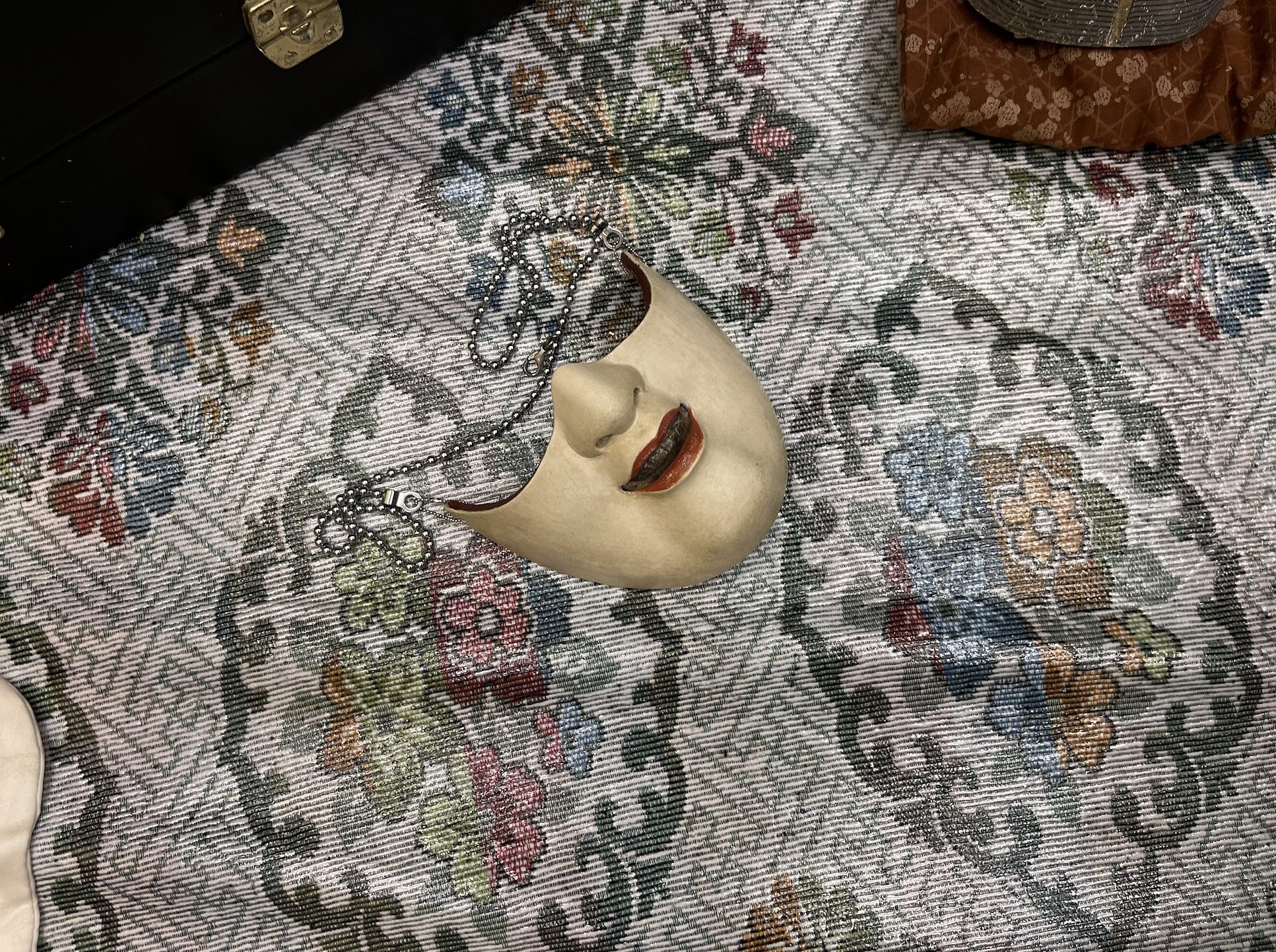

Moreover, Udaka-sensei’s approach to Noh mask carving extends to more modern interpretations. For instance, during the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, she helped found the Takumi New Standard alongside five Kyoto-based artists. With the turbulent times facing Kyoto, the group began as a way to relieve some of the emotional burdens of the pandemic by creating comforting and humorous art. One such work, created by Udaka-sensei, reinterprets a Noh mask as a protective surgical mask, done by removing the top portion of the mask.

(Image: SoraNews24; Creator: Keiko Udaka)

Some of the other modern ways Udaka-sensei approached this artistry is through its representation on digital spaces and gaming. On Rarible, an NFT marketplace, she allowed the masks to exist on its own as an artform, away from the performance that usually accompanies the masks. Under the larger Sukiyaki Japan umbrella, which features a large collection of traditional Japanese artworks and whose mission is to “disseminate traditional Japanese crafts to the world and enliven the industry,” Udaka-sensei has a series of around 32 NFTs of Noh masks on the marketplace. Beyond the NFT space, Udaka-sensei has also collaborated with the game Apex Legends for their Golden Week sale celebration. For the game, she created a mask of the Wraith’s Demon Skin which was handed to a lucky individual through a giveaway that the game hosted.

(Image: Noh Mask #05 Doji by Sukiyaki Japan of Rarible; Creator: Keiko Udaka; Photographer: Hiroko Nishihara)

(Image: Apex Legends and Udaka Keiko)

In all her art making process, it is evident that each mask is created with great care and attention to detail. In an interview with the documentary Noh Masks (面, Men): The Spirit of Noh Theatre, Udaka-sensei says that when she knows what Noh performance the masks will be used for, she “[thinks] of the character’s story and imagine how the character will move.” In the interview, it is clear that in the process of creating Noh masks, it is vital to bring the life of the character through the masks and help spark the essence and soul into the masks during the creation process. Regarding the liveliness that occurs in creating these masks, themes of Inochi as it relates to spreading Inochi and the circulation of Inochi is clear as the creation process involves unleashing life into the masks, which will then be used by the performers.

Question:

- In your interview with Apex Legends, you mentioned that you take medication before you start carving to remove daily distractions and to pay respects to nature. I was wondering if you can describe a bit more about this preparation process and the role of the environment that goes into carving?

- From your NFT collection and collaboration with Apex Legends, what do you envision the future of Noh to be like as it continues to grow and exist in a more contemporary space?

- Do you have a favorite part or step when creating a Noh mask?

- Has your relationship with the art of Noh differed when becoming an educator as opposed to solely an artisan?

- As a female Noh mask maker in a traditionally male-dominated space, how has your experience been like? Do you think the industry is becoming more accepting of change?

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Reflection:

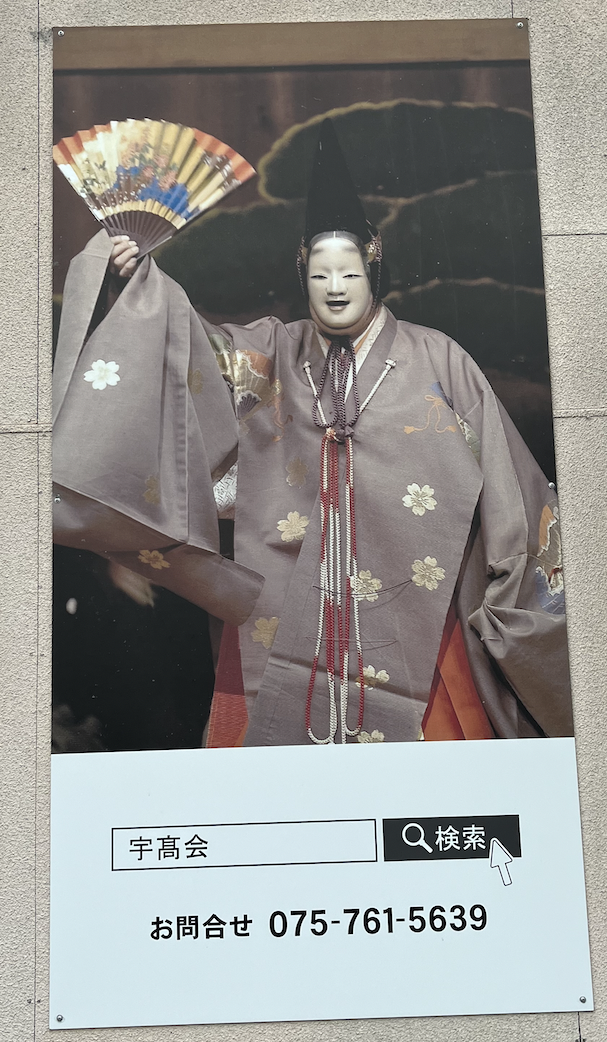

On January 14, our group traveled to the studio of Udaka Keiko-sensei, a “Noh mask [omote] maker from Kyoto who comes from a long family line of individuals specializing in the art of Noh” (Weng). We took a seat around her, and she began by explaining her relationship with the world of Noh theater: her father is a Noh performer of the Kongo school and is also her omote-making master, and her brother is a performer of the same school; she identifies with no particular school, given her profession does not demand such a decision, and she is able to work with each. Udaka-sensei continued her discussion by detailing the omote’s relationship with a performance and how it is designed to reflect the inner and outer attributes of the character. In front of her were about 25 bags, and from each she pulled an omote, beginning with about 10 for young female characters; she then explained how one can determine the relative age of such a character based on the hair design and pattern of their omote. Other omote followed, including exhibitions explanations of those of a young man (ju-roku [lit. 16 (years old)]), warriors without eyes, a dying man, young and elder lions (with different styles depending on the respective Noh school), hannya (crazy women with horns), male demons, and more. Udaka-sensei also showed us some of her own original creations, including omote for new Noh performances (Kikusakude) and a special protective surgical-style mask designed during the COVID-19 pandemic. During our discussion, we also spoke about her Wraith’s Demon Within skin omote designed for the Apex Legends video game. Udaka-sensei proceeded to demonstrate several steps during the carving process, and handed our group some samples of what an omote looks like at a given point in the production process.

On January 14, our group traveled to the studio of Udaka Keiko-sensei, a “Noh mask [omote] maker from Kyoto who comes from a long family line of individuals specializing in the art of Noh” (Weng). We took a seat around her, and she began by explaining her relationship with the world of Noh theater: her father is a Noh performer of the Kongo school and is also her omote-making master, and her brother is a performer of the same school; she identifies with no particular school, given her profession does not demand such a decision, and she is able to work with each. Udaka-sensei continued her discussion by detailing the omote’s relationship with a performance and how it is designed to reflect the inner and outer attributes of the character. In front of her were about 25 bags, and from each she pulled an omote, beginning with about 10 for young female characters; she then explained how one can determine the relative age of such a character based on the hair design and pattern of their omote. Other omote followed, including exhibitions explanations of those of a young man (ju-roku [lit. 16 (years old)]), warriors without eyes, a dying man, young and elder lions (with different styles depending on the respective Noh school), hannya (crazy women with horns), male demons, and more. Udaka-sensei also showed us some of her own original creations, including omote for new Noh performances (Kikusakude) and a special protective surgical-style mask designed during the COVID-19 pandemic. During our discussion, we also spoke about her Wraith’s Demon Within skin omote designed for the Apex Legends video game. Udaka-sensei proceeded to demonstrate several steps during the carving process, and handed our group some samples of what an omote looks like at a given point in the production process.

Before and during our question-and-answer session, Udaka-sensei provided us with a look into the philosophy behind her work. From the beginning, it was clear that the angle at which an omote is held or carried is of great importance: an omote for a young woman can appear happy or sad depending on the angle and lighting, and the sickly man can appear alive or dead if he is upright or lying down. This effect was heightened when, in antiquity, Noh performances would run from sunrise to sunset, and while the warrior would appear at noontime, the nonhumans and crazed women would emerge at dusk. The hannya were a particularly interesting talking point, as they provide insight into the legacy of omote makers: due to Noh’s history as a male-dominated sphere, it appears that some of these professionals had ugly experiences with and grudges against women (perhaps their wives or lovers) and so created characters and omote depicting jealous, monstrous female characters which approach the appearance of a serpent over the course of a performance. Conversely, the male demon characters (the omote that we saw were blood red) are relatively uncomplicated in their nature as evil and powerful. In terms of the creation process, Udaka-sensei explained that a given work could technically require as little as two weeks to complete, however she takes around four weeks in order to have a conversation with and to properly visualize the omote. She noted that, while the modern world stresses the virtue of efficiency, and while other omote-making shokunin work with greater speed, she instead prioritizes: respecting the wood and her tools, and trying to spend lots of time with her works which do not have to perfectly adhere to her various templates. Indeed, she sees her work as a dialogue with the dead, as a process which enables Noh performers to, when they cross the bridgeway at upstage right, move from this world to the other. Another component of her work process is attempting to face her doubts early, before a layer of white paint reveals in full clarity the truth of the omote’s shape and finish.

Some of our group’s – and my – most interesting takeaways from this discussion were seeing the omote as another form of gyō, where natural elements are, over the course of over 120 years (the time it takes for a cypress tree to grow and for a block of cypress wood to dry), manipulated by human hands in order to access and create a bridge to the spirit world. In this way, the natural (sō) and the human (shin) are brought into harmony and united under a common purpose, to create a character or a god. In seeking a form of imperfect perfection, Udaka-sensei blurs the boundary between the self and art, as she breathes life into wood and paint in order to transform it into another animate being. Furthermore, she is expanding the scope of her craft, in person and online, and spreading knowledge of omote-making to a broad base of other shokunin, artists, and creative individuals. In conclusion, I would like to share one of Udaka-sensei’s questions: What kind of picture can truly capture a person’s spirit: a tracing or a sketch? For her, it is clearly the latter, and I would have to agree.