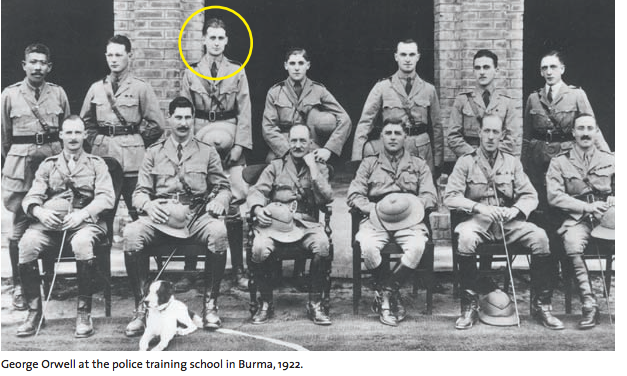

In George Orwell’s “Shooting an Elephant,” he elaborates on the complicated and often blurred power dynamics between Imperial Britain and present-day Myanmar (Burma at the time), describing how he is unlucky enough to be in the worst position of all: a white police officer in Moulmein, a Burmese town. While Orwell due to his ethnicity and official position possesses an objective power over the Burmese at the surface, it is clear as he tells his story of shooting the elephant that this is not the case.

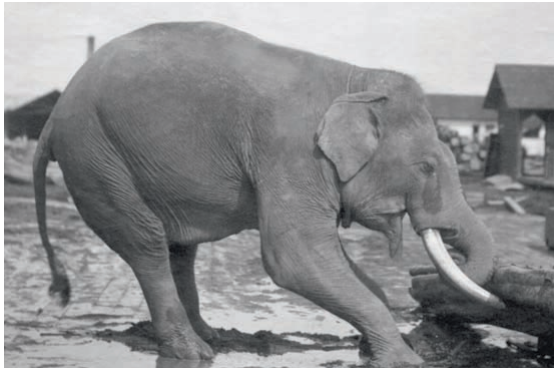

To me it is clear that after Orwell goes against his will and shoots the elephant to “avoid looking (like) a fool,” he officially acknowledges that despite his official government position, he has less power than both the British, who he hates, and the Burmese people over whom he rules. In his decision to shoot the elephant he succumbs to British law as he says that “legally I had done the right thing, for a mad elephant has to be killed, like a mad dog,” and the will of the Burmese people simultaneously, as he fights an internal battle in deciding whether to act on what he personally believes or what will grant the most approval from the Burmese crowd that is watching him. All in all, Orwell is stuck between a rock and a hard place as he is constantly burdened with serving Imperial Britain and striving for the approval of the Burmese, both of whom he has mutual disdain for. As a result, the official power that is granted to Orwell by Britain proves to be inferior to the unofficial power that the Burmese hold over him in seeking their approval when shooting the elephant, showing that true power does not always lie visible to the naked eye.