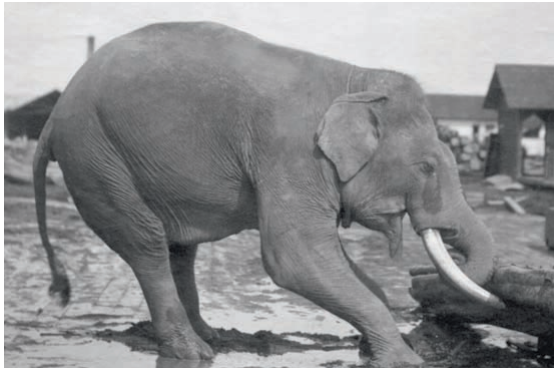

In George Orwell’s “Shooting an Elephant,” it seems to me that no one present at the scene possessed any power over their actions. Orwell, compelled by the system of domination present in British colonies, had to shoot the elephant. The Burmese onlookers, compelled by likely deprivation of both resources and feelings of personal control, had to demand Orwell’s horrific act. Orwell was forced to wear a mask, as others have said, to uphold the power of the British Empire. The Burmese were forced to demand entertainment and meat.

In Orwell’s telling, each actor seemed to have lost their individualism to the state. Without each group performing their role in this scene, the imperial British state would fall apart, as hinted at in the “Parable of the Green Grocer.” Complete domination over peoples as is described by Orwell in passing (references to terrible treatment of incarcerated Burmese and the disregard for the life and property of Burmese people) necessitates a flawless performance in which the state is upheld above all else. Insults and poor refereeing are just the sort of actions that allow one to see that everyone in Orwell’s story is indeed playing a part, rather than believing in the state. However, when it comes to moments of demonstration of power, roles much be executed so that the state of the British empire is upheld. Thus I would argue, that each individual in this case took actions in a performance staged for furthering the power of the state.