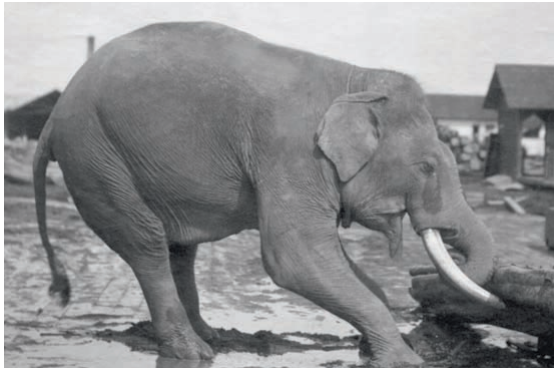

In “Shooting the Elephant” by George Orwell, the power appears to be unequally divided between the British Empire, and the Burmese citizens. Orwell himself, a British officer, wields almost no power. In vastly different ways, Orwell is subservient to both the British officials, who are known to be his superiors, and also the Burmese citizens, who he is supposed to have power over. The British Empire has direct power over the Burmese citizens, as Orwell states, “I was all for the Burmese and all against their oppressors, the British”. The British clearly have power over the Burmese, but the fact that this statement by Orwell was modified to be “theoretically and secretly” expresses the power that the British had over him as well. This relates back to Scott’s argument that the oppressed are conscious of their oppression and secretly condemn it. In addition, the Burmese have power over Orwell through their expectations of how he, and the rest of the British officials, should act. Orwell admits that he “did not want to shoot the elephant” and he only ended up shooting it “to avoid looking like a fool.” Orwell was bound by what the Burmese thought an officer should do, so he had to comply despite it not being what he wanted, which is a form of power being exerted. The little power Orwell has does not come from his status as a British officer, rather it stems from the fact that he is human. Ultimately, the elephant died and the gun was in Orwell’s hands, displaying the power humans exert over all other animals in the world.

Category Archives: Second Blog: Power

Shoot

One of the most interesting arguments from Orwell’s account is “when the white man turns tyrant it is his own freedom that he destroys.” This closely parallels many of the reading we have considered, especially the “As if” piece, as it highlights the duality of power in any system of subordination. On one hand, the Burmese have little political or salient influence, but on the other, Orwell and the other European officers are equally limited by the mask of authority they wear. Both the authority and the victims of this authority also seem to be in disbelief regarding the reality of the power system, yet they act in accordance with it with their public mask. The private one simply cannot believe that any of these actions are justified.

Regarding the shooting of the elephant, Orwell has the ultimate power – he can always decide to shoot the elephant or not. However, because he must play that role, the Burmese, with their contribution to the power system, are equally powerful in making him act in accordance to it. Orwell thus has no choice but to shoot the elephant.

Power – Second Post

In Orwell’s “Shooting an Elephant”, both the native Burmese and the British officers have power, but neither group has complete power. It is the partial power held by each group that limits the power of the other.

By virtue of his position in the colonial hierarchy, Orwell has power over the native Burmese. As a police officer, he enforces the rules and punishes those who break them. The Burmese also hold power over Orwell and the other colonial officials. The ‘everyday acts’ that Scott describe such as spitting betel juice on British women in the market and tripping Orwell in football games erode Orwell’s power. The acts check Orwell’s power but fall short of full rebellion because Orwell’s power in turn checks the power of the natives.

Ironically, the same partial power also reinforces the power of the other. The natives resent British power, which motivates the small acts of defiance that erode the colonial power. To Orwell, the shooting of the elephant demonstrated the passive power of the natives, but to the natives the incident reinforced the image of Orwell as a powerful, armed colonial authority. In this way the partial power dynamic is self-enforcing.

Power is Fluid

To Orwell, power is not fixed. It is extremely abstract and able to manifest itself in many ways across different situations. At a first glance, it would probably be assumed that the Europeans had more power in comparison to the Burmese, considering it was the Burmese who were being dominated. However, as Orwell’s essay “Shooting an Elephant” unravels, one can see that the Burmese have a significant amount of power as well in different unassuming ways.

When Orwell brought his gun to the elephant scene, he assumed power. Whoever assumes power, consciously or in this case, subconsciously, is met with those who expect a use of that power. This expected use of power is a form of power in itself, for it is forcing the other side to exercise its authority. “Here was I, the white man with his gun, standing in front of the unarmed native crown—seemingly the leading actor of the piece; but in reality, I was only an absurd puppet pushed to and from by the will of those yellow faces behind (Orwell, 3). By assuming this authoritative role, Orwell simultaneously limits his own freedom, and subjects himself to the command of the Burmese.

A Complex Power Dynamic

In Orwell’s account no one has complete power. I would say that the power is mostly divided between the Burmese and the British Raj, while Orwell himself has little power. The Burmese have power over Orwell through (as Scott explained) the little acts of resistance that they perform on a daily basis. However, at the same, to them, Orwell represents the power that the British Raj posses that necessitate these acts of resistance. In this way, the question of who has power is complicated, just as it is in almost every society. No one ever has complete power because of the way that people can resist. Additionally, since power is such a fragile concept, those who “have power” are constantly in fear of losing it. In this way, they do not in fact have complete power. This creates for an interesting dynamic because the Burmese dislike Orwell for the repression that he represents; Orwell dislikes the Burmese for the way they treat him, as well as the British Raj for forcing him to do this job. In this way, out of all three entities, the British Raj has the most power. By playing Orwell and the Burmese off each other, the British Raj maintains its power. If the Burmese and Orwell were to come together, it would be much more difficult for the Raj to maintain order and keep power. However, since Orwell and the Burmese are unable to come together, the Raj remains the most powerful entity in the region.

Power

“The sole thought in my mind was that if anything went wrong those two thousand Burmans would see me pursued, caught, trampled on and reduced to a grinning corpse like that Indian up the hill. And if that happened it was quite probable that some of them would laugh. That would never do.”

Who has power in Orwell’s classic account, and why?

https://hilo.hawaii.edu/~tbelt/Pols360-S08-Reading-ShootingAnElephant.pdf