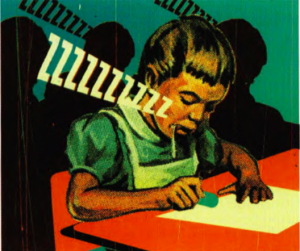

Gatto unveils a critical flaw of the United States’ schooling system — the shortcoming that we are teaching our kids to think solely within the capacity of our mundane curriculum. We are teaching students to fall victim to the “virtual factories of childishness” (Gatto 34), meaning the bar set for students to challenge themselves to pursue higher level academic interests is low. Moreover, the curricula is rooted in the past and does not promote students to think about the challenges that will be faced in the future. The implementation of our school system, as Gatto points out, stems from Prussia. When the United States galvanized a movement to get American kids in school in the early 20th century officials turned to Prussia’s educational model. The result, while increasing the number of students attending schools across the country, were dismal. Children were thinking reflexively, not critically, meaning their brains weren’t being creatively challenged the way they should have been. The premise of this new system was to churn out students from public schools to be a manageable, mediocre populous to fit the mold of ordinary, mildly talented people. Another notion of Gatto’s I found interesting was that students are “receiving schooling”, but there is a stark contrast to “receiving school” and “getting an education” — the latter of which is more desirable because it encourages students to take their education into their own hands. Reading this article in the context of today’s placed importance on academics, it seems imperative that students take their studies and education into their own hands. Conformity is no longer the status quo many millennials and especially Generation Z adolescents want to partake in in society. Hailing from a city such as San Francisco, a place where innovation and eccentricity has become the forefront of technology, I cannot imagine an educational system that does not bring students up to recognize the importance of exploring their creativity.

Author Archives: Shervin Malekzadeh

Schooled or Educated?

“George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln? Someone taught them, to be sure, but they were not products of a school system, and not one of them was ever ‘graduated’ from a secondary school…

…We have been taught (that is, schooled) in this country to think of “success” as synonymous with, or at least dependent upon, ‘schooling,’ but historically that isn’t true in either an intellectual or a fi- nancial sense.”

John Taylor Gatto paints a rather grim picture of the prospects and possibilities denied by schooling (as opposed to the benefits of receiving an education). Although not all of us attended the sort of public schools described by Gatto in the piece, we have all, in some sense, been schooled or accepted schooling, necessarily, in order to arrive at a place like Williams. At the same time, the evidence suggests a second, more nuanced possibility, namely that while most of participate in schooling in order to have “better lives,” our participation comes at a cost, both financial and political. We rein in our freedom in the perhaps dim hope of becoming “successful,” however defined.

Take this assignment as a provocation. What is your assessment of a meritocracy premised on the ceaseless pursuit of ranking and distinction? Does a context like Williams—or even our class!—reinforce the claims being made in the piece?

Please keep your answers short (no more than 250 words, if you can!). Post your reply using the “New Post” feature (but title it using your own creativity). Make sure to tag it as “First Blog.” Remember to post a reply to a reply by Monday. Simply scroll through the entries and reply to whichever one catches your eye!