Experimental Philosophy

Oliver Goldsmith (1730?–1774) is best known as a novelist, poet, and playwright. But he also published two works in the sciences: History of the Earth and Animated Nature (1774) and A Survey of Experimental Philosophy (1776). The Chapin Library recently acquired a copy of the latter, much rarer title, published after Goldsmith’s death but evidently completed a number of years earlier. Experimental philosophy in this context is another term for what we would now call Physics.

Oliver Goldsmith (1730?–1774) is best known as a novelist, poet, and playwright. But he also published two works in the sciences: History of the Earth and Animated Nature (1774) and A Survey of Experimental Philosophy (1776). The Chapin Library recently acquired a copy of the latter, much rarer title, published after Goldsmith’s death but evidently completed a number of years earlier. Experimental philosophy in this context is another term for what we would now call Physics.

Goldsmith was not himself a learned scientist. He had a large personal library, and at least a passing knowledge of a wide range of sources. These included serious works of science: in his introduction to the Survey, he drops the names of Roger Bacon, Francis Bacon, René Descartes, and Isaac Newton. Elsewhere he draws upon the Comte de Buffon. How much he looked to more complicated works by the likes of Newton, however, and how much to more popular sources, would be a matter of complex analysis. Suffice it to say that in the Survey Goldsmith drew upon many writers, beginning with the ancients, to compile two volumes which (like the earlier eight volumes of the Animated Nature) are a lengthy popularization of the subject.

The result is interesting mainly as an unusual and lesser-known product of a distinguished figure in 18th-century English literature, and as a popularized treatment of science in that period, rather than as an introduction to Physics one could reliably recommend to students. Goldsmith’s reputation for error in the Animated Nature precedes him, and the Survey is not, shall we say, driven by the author’s passion for his subject. By the end of the second volume, Goldsmith seems to have wearied of the task: in his final paragraph he concludes

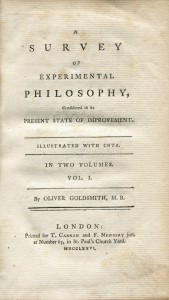

Shown is the title-page of volume 1 of Goldsmith’s book. This set has the added interest of having been owned by a woman, Caroline Anne Horde, who signed both volumes in March 1791. This may have been the Caroline Anne Horde, spinster of Bath, whose portrait was painted by Gainsborough Dupont.