Jocelyn Wexler

I attended an elementary school on the North Shore of Boston, a region encompassing coastal towns and cities stretching from Boston to New Hampshire. The boundary between my elementary school and the forest behind is lined with rocks. My childhood memories are full of this rock wall. Crossing this line of rocks was against the rules; so obviously, my classmates and I spent all of our time crawling over them, dying to go into the forbidden forest behind the boundary. Most of these rocks had been moved there to make the wall; however, the largest one, stuck deeply in the ground, had not been put there by humans. When I was younger, I always wondered how this rock got there.

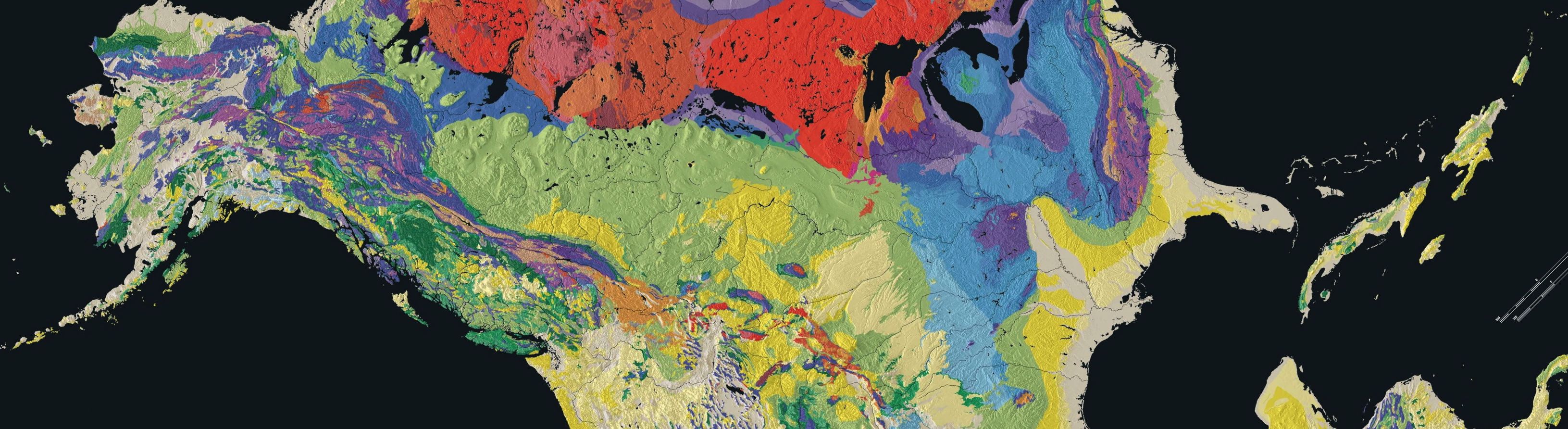

Figure 1: The Laurentide Ice Cap in North America, including its coverage of Massachusetts (U.S. Geological Survey).

One of the questions I should have asked myself about the rocks around me is where the rocks underneath my feet came from. The North Shore is the product of hundreds of millions of years of geologic events. It is part of an exotic terrane, a piece of land that originated from elsewhere (Raymo & Raymo, 2007). The North Shore’s exotic terrane is called Avalonia. Avalonia is a volcanic island arc that most likely came from Gondwana, a supercontinent, which is a landmass made up of multiple continents (Thompson, Grunow, & Ramezani, 2010). Around 550 million years ago, a process called plate tectonics caused Avalonia to break off Gondwana and head towards proto-North America (Goldner & Allen, 2009). Plate tectonics are driven by the hot convective mantle deep in the Earth and cause landmasses to move over the globe (Raymo & Raymo, 2007). About 400 million years ago, during the Devonian Period, plate tectonics also caused a mountain building event known as the Acadian Orogney. In the Acadian Orogoney, Avalonia was crushed between Baltica, modern day Europe, and proto-North America as they collided and Avalonia accreted onto proto-North America (The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of Northeastern US), (Raymo & Raymo, 2007). This crush turned some of the igneous rock that made up Avalonia into metamorphic rock, which is rock changed by high heat and high pressure (The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of Northeastern US). The metamorphosed rocks were later covered by sedimentary rocks (Goldner & Allen, 2009). Following the breakup of Pangea, 200 million years ago, the North Shore experienced a period of erosion, deposition, and lithification, which includes compaction and cementation (Goldner & Allen, 2009). This process forms sedimentary rocks, which are rocks composed of pieces of pre-existing rocks (The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of Northeastern US). The Avalon terrane is important to the North Shore for a few reasons. First, without the Avalon terrane, the coast might be many miles westward. The type of rock in Avalonia is also important; the granite, a type of igneous rock that makes up the bedrock, was quarried in the past (Martin, 2008).

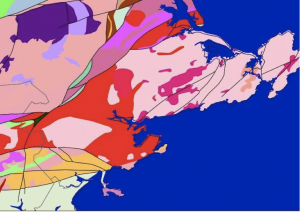

Figure 2: A geologic map of part of the North Shore of Boston. The map shows the granite (the light pink) found in the region (U.S. Geological Survey).

The North Shore was affected by another geological event that occurred millions of years later: the Laurentide Ice Cap. This ice cap left behind the large boulders that are so prominent in my childhood memories (Martin, 2008). During the Wisconsin Glacial Stage, which began 80,000 years ago, ice advanced and retreated over North America (Goldner & Allen, 2009). Towards the end of this stage, around 25,000 years ago, cooling extended the reach of the ice cap, and by 21,000 years ago, the Laurentide Ice Cap extended over all of Massachusetts (Figure 1) (Martin, 2008). Around 14,000 years ago, the climate warmed and the ice cap began to melt and recede northwards (Raymo and Raymo, 2007). As the ice cap melted, it scraped off millions of years of sedimentary rock, exposing the granite underneath (Figure 2) (Martin, 2008). This granite is incredibly dense, making it particularly prized by quarriers (Martin, 2008).

As the ice cap retreated, it also left behind the glacial erratic boulders that are found frequently throughout the North Shore (Martin, 2008). Glacial erratic boulders are pieces of rock that an ice cap erodes and carries as it advances over thousands of years; as an ice cap recedes, these rocks are put down as they melt out of the ice (Raymo & Raymo, 2007). Some of the erratic boulders on the North Shore came from as far north as Newfoundland (Martin, 2008). These are the rocks that dominate my childhood memories – rocks seemingly put down randomly and out of place with their surroundings.

In addition to affecting the rock type on the North Shore, the Laurentide Ice Cap also affected the position of the coastline (U.S. Geological Survey, 2009). The retreat of the ice cap affected sea levels according to a theory called Isostatic Rebound (U.S. Geological Survey, 2009). This theory says that oceanic and continental blocks seek equilibrium, and when the weight pressing on either or both blocks changes, like the melting of ice on the continents, the relative position of oceanic and continental blocks changes to regain equilibrium (Joseph, 1996). The position of the coastline greatly affected the history and economy of the region. Beverly, a city on the North Shore, served as George Washington’s naval base in 1775 (Braudo, 2010). Gloucester, another city in the area, has a long history of fishing, as depicted in the film The Perfect Storm.

When I return with my classmates for reunions, we climb the rock wall again, reliving the games we played as children, the battles won and lost. The boulder never seems as big as I remember it, but now as I sit on it, the boulder has much more meaning. The boulder knows the stories of my childhood, and I finally know its story too.

Figure 1: The Laurentide Ice Cap in North America, including its coverage of Massachusetts (U.S. Geological Survey). Figure 2: A geologic map of part of the North Shore of Boston. The map shows the granite (the light pink) found in the region (U.S. Geological Survey).

Figure 3: An Erratic Boulder from Massachusetts (Boulder Erratic, Borderland State Park).

Works Cited

Boulder Erratic, Borderland State Park [Photograph]. Retrieved November, 2014, from http://baystatements.blogspot.com/p/bay-circuit-directory-south.html.

Braudo, Britt. (2010, October 14). Beverly or Marblehead? Birthplace of American Navy Still Up for Debate. Wicked Local. Retrieved from http://www.wickedlocal.com/article/20101014/News/310149609

Goldner, Mark, & Allen, Deb. (2009). Geology of Boston. Retrieved from http://www.bostongeology.com/boston/geology/geology.htm

Goldner, Mark, & Allen, Deb. (2009). Geologic Timeline. Retrieved from http://bostongeology.com/geology/fieldtrips/fieldtrips.htm.

Joseph, L. H. (1996). Isotopic Rebound. Retrieved from http://www.umich.edu/~gs265/isost.html

Martin, Margaret. (2008). Laurentide Glaciation of Massachusetts Coast. Retrieved from http://academic.emporia.edu/aberjame/student/martin1/laurentide.html

Raymo, C., & Raymo, M. E. (2007). Written in Stone: A Geological History of the Northeastern United States. Delmar, NY: Black Dome Press Corp.

Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the Northeastern US. Exotic Terranes. Retrieved from http://geology.teacherfriendlyguide.org/index.php/geologic-history/exotic-terranes

Thompson, M. D., Grunow, A. M., & Ramezani, J. (2010). Cambro-Ordovician Paleogeography of the Southeastern New England Avalon Zone: Implication for Gondwana Breakup. Geological Society of America Bulletin, 122, 76-88. doi: 10.1130/B26581.1

U.S. Geological Survey. (2009). High-Resolution Geologic Mapping of the Inner Continental Shelf: Cape Ann to Salisbury Beach, Massachusetts. Retrieved from http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2007/1373/html/intro.html

U.S. Geological Survey. Massachusetts Geology [Map]. Retrieved December, 2014 from http://mrdata.usgs.gov/sgmc/ma.html.

U.S. Geological Survey. Pleistocene North Ice Map [Map]. Retrieved November, 2014, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laurentide_ice_sheet#mediaviewer/File:Pleistocene_north_ice_map.jpg.