By Didier Jean-Michel

My hometown, West Hempstead, New York, lies on Long Island, a landmass with an interesting geological history just east of New York City. Summers on Long Island were the best, with sandy beaches or rocky shores not far away. While the island today is most suburbanized (asphalt: everywhere), there is still a lot of evidence of its geological history.

Long Island’s “basement” bedrock is 230 to 350 million years old and is made of metamorphic rock (Merguerian and Sanders 4). The upper portion of Long Island’s geological layers were formed between the Upper Cretaceous Period (72 to 100 million years ago) and Pleistocene Epoch (.12 to 2.5 million years ago), and consists of mostly sedimentary elements: gravels, sand, and clay (see Bedrock Geology map here, provided by RegentsEarth) , which were all deposited by glaciers (M and S 5). This is a stark difference from New York City, which is located on a more solid rock. This is why taller skyscrapers can be built in Manhattan, but tend not to be on Long Island.

On Long Island, the names North Shore and South Shore are used to describe two parts of the island. The North Shore tends to be more hilly and rocky where the South Shore is flat and sandy. The change in gradient and topographic make up from north to south is evident of glacial movement, so the Long Island of today was shaped by glaciation. The glacial movement sculpted the Cretaceous layer, creating a rocky North Shore and a gentle slope down to the South Shore, and outwash from these glaciers covered the island with sand and sediment (M and S 5).

During the last glaciation (the Wisconsinan glaciation, which lasted from approximately 85,000 to 11,000 years ago), glacial movement pushed south through New England and stopped at what today is know as the Ronkonkoma terminal moraine, which is a glacial depositional formation at the terminus of the glacier formed when it pushes loose sediment as it moves along. Think of the way a bulldozer pushes gravel into a mound: moraines work the same way. Another moraine, the Harbor Hill terminal Moraine was formed after the Ronkonkoma moraine, and together, the two moraines make up the north and south forks at the eastern end of the island as well as the glacial Lake Success at the western end, where the moraines meet (M and S 31-32).

The part of the island south of the Ronkonkoma terminal moraine is know as an outwash plain, which is another glacial depositional feature created by melted glacial water that flows sediment out from underneath the glacier and deposits it at the end point of the glacier, creating a flat plain of sediment. My town is located on this outwash plain on the South Shore, which is known for sandy beaches, whereas the North Shore is better know for rocky shores on the Long Island Sound.

With a relatively low elevation (the highest point is Jayne’s Hill with an elevation of 401 feet above sea level), Long Island could be subject to flooding and possibly even total submergence should sea level continue to rise. Because it was formed by glaciation, fossils are not very common on the Island.

Long Island is known for it’s beautiful beaches like the Hamptons, and it attracts tens of thousands of visitors every summer, so tourism plays a role in the economy. The receding glaciers in the Pleistocene left the sandy beaches of the South Shore, and today many tourists and year-round residents appreciate them. The barrier islands south of the mainland are also home to more vacation homes. Occasionally the ocean breaks through these barrier islands and changes the coastline. After Hurricane Sandy in 2012, an inlet was created at the western end of Fire Island, a 31-mile barrier island a couple of miles off the mainland.

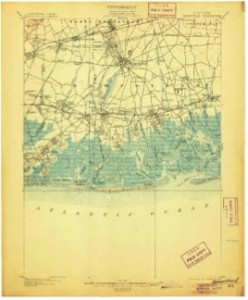

Figure 1- Hempstead Quadrangle Clark, Walcott, and Wilson. 1903. Geologic map of Hempstead Quadrangle: The Geological Survey. Scale 1:62500. Map

Long Island was also a major leader in aviation. In east Nassau (one of the two counties that make up Long Island), Charles Lindberg took off in the Spirit of St. Louis for the first solo trans-Atlantic flight, a proud achievement for mankind. Soon after, many aircraft manufacturers like Grumman Aircraft established themselves in this area. East Meadow and the surrounding towns would make up what was known as the Cradle of Aviation. What made this area of Long Island so conducive to aviation were the large flat prairies that were suitable airfields and tarmacs, in addition to their relatively close distance to New York City. The prairies were a result of the outwash plains left by the glacier.

Long Island certainly has an interesting geological history as a result of glacial movement, which makes it relatively younger than Upstate New York, which experienced varying degrees of mountain building. It’s an outlier in an area of metamorphic bedrock and mountainous regions. But its uniqueness makes it a special and beautiful place to live.

Works Cited

Merguerian, Charles, and John E. Sanders. Trips on the Rocks- Guide 13: Glacial Geology of Long Island, New York. N.p.: Duke Geological Laboratory, 2010. PDF.

New York Geological Map; www.RegentsEarth.com http://www.regentsearth.com/Illustrated%20ESRT/Page%203%20(Bedrock%20Geology%20Map)/Page%203%20Index.htm

Clark, Walcott, and Wilson. 1903. Geologic map of Hempstead Quadrangle: The Geological Survey. Scale 1:62500. Map.